5: Doctrines of Causality

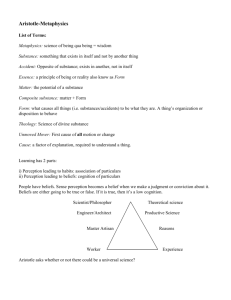

advertisement

5: Doctrines of Causality The modern concept of causality, even if philosophically a challenge, is rather simple. A thing or an event causes another thing or event. The first thing or event is called a cause, the second is called an effect. If I hit the tennis ball with my racket, my hitting is the cause of the ball flying. In ancient philosophy the concept of cause is a lot more elaborate. The modern understanding of cause is what the ancients would know as the efficient cause, the causa efficiens. In Aristotle’s classical scheme of causes this would be one of totally four causes, viz. the formal cause, the material cause, the efficient cause, and the final cause. In this chapter I shall first comment on Aristotle’s doctrine and point to some further developments in late antiquity. Next I shall discuss an important feature of Neoplatonist metaphysics and physics, viz. the Plotinian idea of double activity and the concept of procession and conversion that are central to Neoplatonist and Christian thought. Some light shall also be shed on what has been called the metaphysics of prepositions, which is of importance for developments in Christian cosmology and soteriology. 5.1: The ancient doctrine of causes Aristotle argues that there are four kinds of causes. 1 Everyone who has tried to read something written by Aristotle has come across this doctrine one way or another. The four causes may be understood as four ways of explaining what is responsible for the being of a thing, and for changes that take place in things or in relation to things in the world. The efficient cause is on the one hand the productive cause of the existence of something, like the male, according to Aristotle, is responsible for offspring in natural generation. On the other hand the efficient cause effects certain changes, for instance from being white to being black, in already existing things. The material cause is that 1 Cf. Physics book 2, chapter 3. out of which something is made. The formal cause is the sum of the essentially defining characteristics immanent to something. The final cause is the purpose of the being of something, or what attracts something to its end. In Neoplatonism the number of causes is increased to six.2 The paradigmatic cause and the instrumental cause are added to Aristotle’s four causes. Of course, Neoplatonists generally held that all of these causes were anticipated in or already worked into Plato’s dialogues. We have already seen how the paradigmatic cause works. In Plato’s Timaeus we found that the Creator contemplated the so-called Paradigm, the sum total of Forms, when he made the world. The paradigmatic cause is, therefore, the pattern according to which something is made. In the most proper sense it is the Forms as cosmic pattern. Developments in Platonic theology among Platonists after Plato culminated with the doctrine that the Forms are the thoughts of God, so that the Paradigm or paradigmatic cause is located in the divine Mind.3 The instrumental cause is that which enters a process of change and contributes to the result. Simplicius illustrates the following way:4 treatment for a disease is the efficient cause of health. There are, however, intermediate stages on the way from the beginning of the treatment to the end, and the end is being cured from the disease. This end is, of course the final cause. What are these intermediate stages? They involve things like medicine and the use of medical instruments etc. If this is the case, the distinction between instrumental causality and efficient causality does not seem quite obvious to me at least. 5.2: Plotinus’ on double activity (energeia) I would first like to make a terminological remark. The term double activity designates a certain causal scheme. One part of this activity is internal the other is external. In my usage these terms are of a wider application, and do 2 Cf. Simplicius, On Aristotle Physics 2, 309,1-318,25. Cf. Tollefsen (2008), 27-33. 4 On Aristotle Physics 2, 316,5-15. 3 not exclusively designate Plotinus’ doctrine of causation. The reader has, therefore, to be aware of distinctions in the application of this terminology. One thing is the Plotinian use of this conceptual scheme. The Christian application differs from this, as we shall see.5 As indicated above, we do not now leave the topic of causality, but rather enters the field of central and interconnected ideas in the philosophy of late antiquity, of relevance both for pagan Neoplatonism and for Christian thought. Plotinus distinguishes between three divine entities that are hierarchically arranged, viz. the One, the Intellect or Mind, and the Soul. There is a fourth entity called nature, and on the level of nature matter emerges. We shall start with what a lot of people associate with Plotinus, viz. that he teaches how lower levels of being emanate from the higher principles, basically from the One, the highest Neoplatonic divinity. Plotinus, it is claimed, holds a doctrine of emanation. As a matter of fact, Plotinus uses terms that indicate that this is the case. He speaks of a radiation (perilampsis) from the One, like the radiation of light from the sun, or like the emission of scent from perfumes.6 However, I am quite sure that these ‘likenesses’ in effect are images and metaphors illustrating a difficult but highly sophisticated doctrine of causation. In Ennead 5.4.2 Plotinus outlines what he has in mind. The One, Plotinus says, remains (menei) in an unchanged condition. As it abides such, it remains as intelligible or thinkable, i.e. as something that may be known by a Mind. Consequently, something comes to be next to the One, viz. a thinking (noesis) that thinks that from which it comes. As thinking that from which it comes, this hypostasis is constituted as Mind or Intellect. — How could this process of establishment be highlighted philosophically? The explanation that is given appeals to double activity, and tells that in everything there is an activity that belongs to the essence (ousia), and an 5 I am indebted to Emilsson (2007) for some basic aspects of the Plotinian doctrine of double activity. The Christian application is worked out by me in Activity and Participation (a draft for a book, sent to the publisher). 6 Ennead 5.1.6. activity that goes out from the essence. There has to be, then, some activity internal to the One, that has an external effect which establishes itself as a new level of being, a new hypostasis. Plotinus thinks this principle of double activity is a common structure of causality on all levels of reality, and even below the level of reality as such, i.e. on the level of material things. As a matter of fact, it is highly difficult to understand exactly what goes on at the highest level of generation or creation. We should turn to some of Plotinus’ examples or illustrations from the lower level in order to grasp how the process of double activity may explain generation. In Ennead 5.1.6 he talks of fire as an example. Plotinus explains his doctrine along the following lines: there is an activity that belongs to the essence of a thing, and an activity that goes out of the essence. The activity that belongs to the essence is that essence, and the second activity derives from the first one and is different from it. Fire contains a heat that fills up its essence. This heat must be understood as an activity of heating that is the essence of fire as such. I suppose we could acknowledge that this is a distinctive and separate phenomenon. It should also be rather easy to acknowledge that this internal activity of fire lets off an effect that is somehow an externalized activity of heating. Likewise we may go to Plotinus’ mentioning of snow and perfume in Ennead 5.1.6. We have the same picture, snow is essentially a cooling process in itself, but it lets off a external cooling process which may be experienced around it. And perfumes are essentially an active substance internally, that it experienced beyond its own limitation in time and space: we may scent the perfume from a distance. There is something we should note about these examples that strikes me as especially important. It we consider the internal process as a cause and the external result as an effect, we clearly see that there is a certain connection between what goes on internally and what goes on externally. Cause and effect have some quality in common. It is because the internal activity has a certain quality that the external activity has its distinctive quality. Both Aristotle and his commentator Alexander of Aphrodisias points out that there are instances in which cause and effect have the same qualities, like fire and things heated.7 Further, in the generation of substances a substance generates something of the same species as itself. However, Aristotle sees that a quality does not have to be generated by a quality of the same kind, when he acknowledges that hardness is generated, not by what is hard, but, for instance, by heat that dries out moisture from, let us say, clay. This last is important. Plotinus says:8 ‘It is not necessary that one should possess what one gives. Rather, we should think in such cases that the giver is greater, and the given less than the giver.” One should note, however, that the immediate effect of an internal heat is heat, while dryness is a second effect. On the one hand, in the instances we have considered from Plotinus, it is quite easy to understand his point of double activity as a causal scheme whenever the same quality is active in cause as well as in effect. On the other hand, Aristotle’s example of the quality of hardness would not function in any different way, since it is the internal activity of heat that produces an external heat that dries out the moisture form clay. However, in this instance we may acknowledge that heat is the cause of a quality that differs from itself as well, viz. dryness. When we turn to intelligible realities things become more intricate and definitely more difficult to explain. We saw above that the One remains in the condition of intelligibility, and this, as an internal activity, has the external effect of being thought. Its being thought is on a secondary level, which means that like the heat springing from the internal heat in fire, Intellect or Mind springs from the internal activity of the One. If such is the case, to remarks is appropriate. (i) The strength of the idea is that there is somehow a common quality in cause as in effect. (ii) The weakness is that it is easier to see how heat follows heat than to see how Intellect follows intelligibility. One could, probably, say that it is only sensible to talk of something being intelligible if there is an intellect to think it. But this does not make this creation-process intuitively evident. However, there are more difficulties. In Ennead 5.1.6 Plotinus says: ‘So if there is a second after the One 7 Aristotle, GC 1,5: 320b17-21 and Alexander, In Metaph. 147,15-28. [Cf. Sorabji, The Philosophy of the Commentators, Physics, 141-3.] 8 Ennead 6.7.17. [Cf. Sorabji, 144.] it must have come to be without the One moving at all, without any inclination or act of will or any sort of activity on its part.’ The One, according to Plotinus, is even beyond activity.9 The One of Plotinus is not self-thinking thought. It does not think at all. It is not even conscious of itself. 10 Even so the One is an activity.11 This activity is in Ennead 6.8.16 described as hypernoesis, a ‘beyond-thinking’. Whatever this may mean, the One obviously is in an even better condition when it comes to ‘mental’ activity than any kind of thinking or contemplation we may be able to conceive. Despite his desire to elevate the perfect condition of the One beyond any human comprehension, Plotinus seems to stick to the idea of the One as somehow intelligible.12 One wonders why, and one wonders how this intelligibility enters the picture. Whatever possibilities we have to penetrate deeper into the creation-process of the Intellect, I think we should stick to the following description that, I suppose, give us some idea of what Plotinus thinks is going on. Since the principle of double activity is generally observed in nature, it is reasonable to apply it to the description of higher things as well. In that case, we should just admit that there is an internal activity of the One that lets off an external activity as an effect. Even if we cannot say anything about how the Intellect emerges, we may be in a more favourable situation when it comes to how it gets constituted. We should note, however, that we are not talking of processes that go on in time. What we are talking about is eternal processes, i.e. activities that are eternally dependent on prior activities. Given that Plotinus has two basic concerns in this connection, viz. (i) to claim a general principle of causation and (ii) to preserve the tension between absolute unity and multiplicity, he seems to run into difficulties trying to put them both together when it comes to the explanation of how the highest divinity creates what comes next to it. The question we should 9 Ennead 1.7.1. Ennead 3.9.9. 11 Ennead 5.6.6. 12 Cf. Ennead 5.4.2. 10 concentrate on, then, is how the Intellect is constituted, not on how the One generates. How then, is the Intellect constituted? Vi should first note that in processes of generation the generated thing proceeds and converts in relation to its source.13 The procession accounts for the difference between cause and effect: if a second thing is going to be, it must be different from the first. However, proceeding does not account for what a thing is, only for the fact that something emerges in its difference from its source. But for the new entity to be turned into a new hypostasis, the conversion has to take place. I construct the following picture of the generation of the Intellect from a comparison of several texts:14 the procession is the same as the activity out of the essence of the One. This activity emerges as a potential act of contemplation in which the One becomes a potential object of contemplation. In the act of conversion the activity of the essence of the new entity is established as a new hypostasis: the potential act of contemplation becomes an actual act of contemplation, this actuality or activity (these translates the same Greek word, energeia) is a contemplation of itself as derived from the One, and as such a self-contemplation it becomes the hypostasis of the Intellect. The above try to highlight the causal process of generation does not, of course, clear up all the difficulties surrounding the generation of hypostases or entities in the Plotinian system, but it has to suffice. At least I hope I have contributed a bit to some better understanding of the sophisticated philosophy of Plotinus. There is one more important thing to take notice of before we move on, viz. the hierarchical character of Plotinus’ concept of causality: the cause is greater than its effect.15 I suppose Plotionus has concept of horizontal causation, like when father engenders his son, but the causal scheme of double activity and procession and conversion is, in Plotinus, conceived to explain generations in the intelligible realm, as well as sensible changes in 13 Cf. Ennead 1.7.1 and 5.1.6-7. Cf. Ennead 5.2.1; 5.4.2; 5.3.11; 5.6.5; 1.8.2; 3.8.11. 15 Ennead 6.7.17. [Sorabjii, 143-4.] 14 which cause could reasonably be taken to be greater than its effect. The illustrations applied above would be if this kind: fire and heat, perfume and scent, snow and cold, etc. One might ask, however, if this causality of double activity as conceived by Plotinus necessarily secures such a sequence of greater and lesser. As a matter of fact, I cannot see that it necessarily does. It is at least not self-evident to me that the effect needs to be on a lower ontological level in the scale of being that the cause. This feature makes it easier to apply the term double activity, and internal and external activity, when speaking of certain aspects of Christian thinking as well. 5.3: Procession and conversion The concept of double activity involves, it seems, three to four of the six causes mentioned in section 4.1. The activity of the essence is an instance of a formal cause, the activity out of the essence is efficient causality, and the conversion represents final causality. I suppose that the paradigmatic cause may be involved in efficient causality, whenever something is made in accordance with a pattern. Causal schemes are involved in explanation of processes in the different realms of intelligible and sensible nature. The Neoplatonist Proclus () exploits the Plotinian conception of causality in a rather distinctive way. Proclus adheres to the principle, considered above, that causes and effects have the same qualities.16 In a famous proposition from his Elements of theology (35), Proclus says: ‘Evert effect remains in its cause, proceeds from it, and converts upon it.’ This doctrine of remaining, prosession, and conversion is, as we have seen, already present in Plotinus. In Proclus it becomes a central feature of his system. The first part of the proposition probably means that the qualities that occur in the effect are already present in the cause, and in a more perfect way that is. The second part means that the effect is distinguished from its cause. The third part of the proposition means that the effect is fully constituted in its 16 ET 18. [Sorabji 145.] character when it turns to its source and gets constituted as it is somehow filled — metaphorically speaking — with it. In Plotinus we saw that it is the higher principle itself that remains in its own perfection, in Proclus it is the effect that remains in its cause. This, however, could be understood as two sides of the same case: the remaining of the effect in the cause is the preservation on the higher level of the quality that comes to be in the effect on the lower level. What strikes me as especially important with Proclus’ system is his explicit teaching that cause and effect have the same quality, even if the degree of perfection differs: And if they had nothing identical, the second having nothing in common with the existence of the first, could not arise from its existence (to einai). It remains, then, that where one thing receives bestowal from another in virtue of that other’s mere existence, the giver possesses primitively the character which it gives, while the recipient is by derivation what the giver is.17 The scheme of remaining, procession, and conversion is not only found in Neoplatonist systems in late antiquity, we find it in Christian thinkers as well. I shall not investigate the origins of such a scheme in Christian literature, but point to its explicit use in the writings that pass under the name of Dionysius the Areopagite, who might be the first Christian thinker to make extensive use of it. In his De divinis nominibus (4.10, PG 3: 705d) he states: ‘To put the matter briefly, all being derives from, exists in, and is converted towards the Beautiful and Good.’ It is, of course, tempting think that this causal scheme is taken over from Proclus, since scholars have tried to show that he influenced Dionysius. On the other hand, whatever be the case with Dionysius, I do not think that Christian theology just took this idea from the pagan schools. And if the Christians started to use terms and schemes that are similar to Neoplatonic terms and schemes, it is because they felt entitled to do so since their own Holy Scriptures justified it. In support they could appeal to St Paul (Rom 11,36 and Col 1,16-17): 17 ET 18. [Sorabji, 145.] For from Him, and by Him, and to Him are all things: to whom be glory for ever. Amen. For in Him were all tings created, that are in heaven, and that are in earth, visible and invisible, whether they be thrones, or dominions, or principalities, or powers — all things were created by Him, and to Him. And He is before all things, and in Him all things consist. This prepositional metaphysics (cf. the in, by, and to) of St Paul suggests that the world is somehow contained in God, as if God is its paradigmatic cause, that beings proceed from God by an act of creation, that they convert to God, and that God is the reason for their existence. In a general sense, this is what Dionysius intends. In The scheme is further developed in the thought of St Maximus the Confessor. In his 7th Ambiguum he speaks of a ‘procession that keeps together’ and a ‘converting transference’.18 This is the procession and conversion-aspects of the causal idea. The part of the doctrine that concerns remaining is in Maximus connected with his teaching on divine logoi (similar to Platonic Forms in a divine intellect) that are conceived eternally in God as the paradigmatic cause of the cosmos. All beings are eternally present in the divine mind in these logoi. God knows all things He will make, intelligible as well as sensible, in His logoi.19 We shall return to the details concerning Maximus’ thinking in later chapters. 18 19 Ambiguum 7, PG 91: 1081c. Ambiguum 7, PG 91: 1081a.