A Lived Curriculum In Two Languages, Curriculum

advertisement

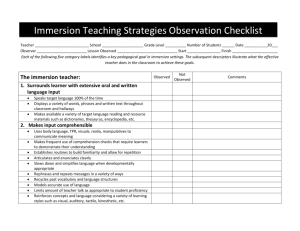

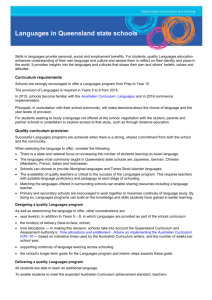

A Lived Curriculum in Two Languages Simone Smala, Lecturer in Education, The University of Queensland and Kate Sutherland, Deputy Principal, Telopea Park School, Canberra Abstract The 21st century will require skills and dispositions of Australian students that allow them to participate in working towards global solutions for global challenges. Language skills and a positive disposition to engage with other cultures will be central to such participation. This article argues that bilingual immersion programs which deliver curriculum content in two languages are amongst the most promising designs to achieve global competencies. These competencies include linguistic skills, positive intercultural dispositions and deep knowledge of world issues. The authors present two examples of successful second language immersion programs in Queensland and the Australian Capital Territory, examined under the lens of globalisation discourses. The findings show that immersion programs offer many opportunities to engage with people, resources and ideals in transnational social fields, and are a viable local alternative to mainstream monolingual schooling in times of economic and cultural globalisation. A LIVED CURRICULUM IN TWO LANGUAGES 2 A Lived Curriculum in Two Languages Introduction Contemporary discourses in education include a focus on globalisation and an internationalisation of curriculum. The preamble of the Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians states that “in the 21st century Australia’s capacity to provide a high quality of life for all will depend on the ability to compete in the global economy on knowledge and innovation” (Ministerial Council of Education, 2008, p. 4). Such a statement presupposes that curricular initiatives must create the conditions for Australian students to become ‘global players’. This paper argues that second language immersion programs present a potential site for preparing students to engage globally. The authors contribute to the research on content and language integrated learning (CLIL, the most widely used term for immersion programs) by comparing and contrasting variables of context and curriculum in two examples of immersion education in Australia. While the research on globalisation and internationalisation covers a wide variety of issues, the focus here will be on the significance of immersion programs in the provision of flexible pathways of schooling in Australia, recognising diverse linguistic, cultural and personal life-worlds and acknowledging the importance of engaging with global linguistic and cultural competencies for all Australian students. The analysis is set in globalisation and internationalisation discourses. The term ‘internationalisation’ was most popular until the mid-1990s and focuses more on border-crossing activities from one national context to the next; ‘globalisation’ discourses incorporate worldwide economic, social and cultural maps which are not bound to national contexts (Rivza & Teichler, 2007, p. 458). Transnationalism is the logical next step in this conceptualisation, defined as the “sustained linkages and ongoing exchanges among non-state actors based across national borders” and characterised by religious beliefs, common cultural and geographical origins and business interests (Vertovec, 2009, p. 3). Key theorist of cultural globalisation Arjun Appadurai proposes five dimensions through which globalisation movements flow: ethnoscapes, mediascapes, technoscapes, A LIVED CURRICULUM IN TWO LANGUAGES 3 finance-scapes and ideoscapes (Appadurai, 1996). While the scope of this paper does not allow for an in-depth discussion of these “flows along which cultural material may be seen to be moving across national boundaries” (Appadurai, 1996, p. 33), we will revisit some of the concepts when they become relevant for our analysis. More specifically for our argument, discourses in globalisation and education include foci on contested legitimacy to inculcate values into the process of educational globalisation (e.g.Spring, 2008), as well as questions surrounding the accessibility of global learning experiences, for example through the use of e-portfolios (e.g. Cooper, 2008). New forms of cultural identities as results of transcultural flows of global media are explored (e.g. Lam, 2006), in particular the 21st century need to prepare students for transnational/transcultural citizenship (e.g. Abowitz & Harnish, 2006; Guerra, 2008). An increased global student mobility comes into focus (Brooks & Waters, 2009; Rivza & Teichler, 2007), and new identity spaces occupied in transnational social fields or third places (Gargano, 2009; Lo Bianco, Liddicoat, & Crozet, 1999). Comparative education research includes potentials to construct new meanings in these international exchanges (Fox, 2007). Many of the theoretical considerations on globalisation issues in education lack practical examples (Aldridge & Christensen, 2008, p. 66). Our paper provides an analysis of two practical examples of how globalisation in education is addressed in Australian settings through curricula in second language immersion programs. For Bourdieu (1991), the curriculum as a reflection of power is an example of an active construction of ‘knowledges’ to be set in concrete institutional settings and wider contextualisation of power. From his perspective, subjects compete for the right to define legitimate knowledge, comprising strategies in a field of struggles. We argue that strategies used in merging and extending curricula in second language immersion programs lead to the emergence of new subject possibilities for Australian students, legitimized by internal criteria that prioritize transnational social fields and ‘third places’. While taking into account comparative measures such as numbers, the makeup of the student and teaching body, and (hidden) values, beliefs and assumptions (Tikly & Crossley, 2002), the analysis follows the proposal of Burawoy et al. (2000) for a ‘global ethnography’ in which global A LIVED CURRICULUM IN TWO LANGUAGES 4 forces, global connections, and global imaginations guide the local lens applied by the researchers. Reimers’ (2009) three interdependent dimensions for global competencies in the 21st century were chosen as specific lenses: 1. A positive disposition towards cultural differences; 2. The ability to speak, understand, and think in languages foreign to the dominant language of one’s native country; and 3. Deep and critical knowledge and understanding of world history, geography, and global topics such as health, climate and economics and their challenges (p.25). These sample themes in the vast array of globalisation literature were selected for their relevance to the research contexts here presented. Simone Smala will present her research findings on the eleven existing second language immersion programs in Queensland middle school settings, with particular reference to a research project that focussed on transcultural curriculum experiences for students in a German immersion program. Kate Sutherland will present her ethnographic study of merging the French and ACT curricula in the French immersion school Telopea Park in Canberra, with a focus on the transnational flows of curriculum cultures. Our paper aims to outline some of the local challenges in implementing a program that teaches curriculum content in a language other than English, but also some of the possibilities such programs present for global citizens of the 21st century. The CLIL Context in Australia Over the past twenty-five years, a growing number of second language immersion programs have been developed in Australian schools. This was in part a response to a growing awareness in Australia that the context of globalisation requires “effectively using multiple languages, multiple Englishes, and communication patterns that more frequently cross cultural, community and national boundaries” (Cope & Kalantzis, 2000, p. 5). In immersion programs, a language other than English is used as the medium to teach curriculum for a variety of year levels, age groups and settings. Due to migration flows and globalisation discourses, bilingual or immersion education plays an increasing role in imagining mass schooling models in many settings worldwide (Garcia, 2009). A LIVED CURRICULUM IN TWO LANGUAGES 5 Australia is beginning to enter this discourse as well. The current project of developing a National Curriculum for Languages prompted the Modern Language Teachers Association of Victoria (MLTAV) to include questions about immersion teaching as preferred second language teaching option in a recent online survey. 71% of the 386 respondents assigned a medium to very high importance to the inclusion of immersion models for a National Languages Curriculum (Modern Language Teachers Association of Victoria, 2009, p. 12). In the recent Australian Council for Educational Research review on Second Languages and Australian Schooling, the author Jo Lo Bianco dedicates several sub-sections to immersion pedagogies and declares them as amongst the most promising design developments in the area (Joseph LoBianco & Slaughter, 2009). In Queensland, a formal evaluation of all Education Queensland Language Immersion Programs was conducted in 2006, finding that “the immersion program model of language education is extremely effective” (cited in Education Queensland, 2007, p. 3). Literature on global competence emphasizes the central role of learning a second language in order to engage deeply with diverse cultures (Hunter, 2004; Lambert, 1996; Reimers, 2009). We argue in this paper that at least some of the envisaged global competencies are inherent in the structural vision of immersion programs. However, globally attractive ideals such as bilingualism and bilingual education “on the ground” involve a multitude of players with a multitude of positionalites to be considered. Delivery of curriculum in a second language necessitates more planning, more scaffolding and the inclusion of additional language elements in the Science, History or Maths classroom. This requires supports from the Heads of several departments, teachers who are willing to take on the extra burden of planning for such lessons and students who are ready for such a challenge. The following sections therefore look further into concepts of global competence, for example second language proficiency and intercultural engagement, and local implementations of such concepts within second language immersion programs at two Australian sites. Context of immersion teaching in Queensland CLIL programs can be seen in many different incarnations around the world, reflecting migration flows, the pressures of perceived global economic forces and time/space connections across A LIVED CURRICULUM IN TWO LANGUAGES 6 cultures. In bilingual societies, programs often start very early at pre-school level. In the vast TESOL field, CLIL is known as “English as the medium of instruction” and is the major teaching form in hundred of International Schools worldwide, often also frequented by local (wealthy) students whose parents construct an English-medium education based on an American, English or Australian curriculum as added value for their children’s chances in a global economy. In Queensland, the concept of immersion teaching usually refers to a late onset partial program of offering approximately half the key learning areas in a language other than English in Years 8-10 (Berthold, 1995; de Courcy, 1997, 2002; Dobrenov-Major, 1998; Tisdell, 1999). At present, there are 12 schools in Queensland that feature immersion programs in French, German, Spanish, Italian, Japanese (including the only primary program), Indonesian and Chinese. Table 1. Immersion programs in Queensland Name of School and Location Language Start Year Of Program Benowa SHS (Gold Coast) French 1985 Mansfield SHS (Brisbane) French 1991 Kenmore SHS (Brisbane) German 1992 Park Ridge SHS (Brisbane) Indonesian 1993 Stanthorpe SHS (Stanthorpe) Italian 1995 Crescent Lagoon SS (Rockhampton) Japanese 1995 (primary program) The Glennie School (Toowoomba) French 1998 Ferny Grove SHS (Brisbane) German 2003 Varsity College, (Gold Coast) Chinese 2005 Robina SHS (Gold Coast) Japanese 2008 North Lakes College (North Brisbane/Sunshine Coast) Italian 2008 Indooroopilly SHS (Brisbane) Spanish 2008 (Data collected Queensland immersion teachers and LOTE Heads of Departments in an email survey, February 2010. Additional data from Education Queensland (Queensland Department of Education and Training, 2010) A LIVED CURRICULUM IN TWO LANGUAGES 7 As part of increasing globalisation and internationalisation discourses from the 1980s onwards, these programs were designed to reach high levels of proficiency for second language learners who were native English speakers. Early research into Queensland immersion programs focussing on a narrowly conceived selection of immersion participants revealed that the conditions (no or little initial second language skills of many participants) were, however, often not favourable for language proficiency, particularly in the productive language skills (Dobrenov-Major, 1998). The 21st century, however, has also seen an increase in “Third Culture” or “Global Nomad” (Langford, 2001) students who spend their schooling in international schools provided by the language community of their country of origin, or only part of their schooling in their home countries. Globalisation discourses that emphasize economic development are generating these major migration flows, and are followed by issues pertinent to multicultural societies and language planning (LoBianco, 2003). Students with diffracted ‘global’ identities (and their parents) are increasingly looking for connections and a ‘home’ for their experiences. Preliminary results from my current large study into immersion programs in Queensland have shown that native, background and heritage speakers are often attracted to immersion programs, across all languages. A typical immersion classroom in Queensland includes native English speakers, native bilingual speakers, global nomad native speakers, with diverse language skills and a variety of support structures at home. At this stage, no final conclusion can be drawn from these phenomena, but the heterogenous nature of immersion program participants in Queensland certainly contributes to the demands on teachers to produce relevant curriculum delivery for immersion cohorts, both in terms of language level and contents. The decision to offer the Queensland immersion programs in three key learning areas, Mathematics, Science and Studies of Society and the Environment (SOSE) reveals a desire to demarginalize second languages. Occasionally, subjects such as Music, Sport or Art may also be offered in addition to these KLAs if suitable teachers are available. Australia cannot be classified as a bilingual or multilingual society similar to countries like Canada, Belgium or Switzerland and does not have an abundant supply of proficient speakers of other languages with teaching degrees. However, our times of global migration and employment movements create the conditions for schools A LIVED CURRICULUM IN TWO LANGUAGES 8 to employ mostly native or near-native speaker teachers, qualified in their subject area as well as being bilingual speakers. The need to find or develop suitable materials to deliver the local curriculum in a second language often steers these immersion teachers towards contemporary mediascapes, engaging in the possibilities afforded by the web, satellite television and classroom hardware like interactive whiteboards. Immersion teachers in Queensland are often at the forefront of new media usage in their schools, developing new literacy skills in their search for authentic language materials (Smala, 2009). The context in Queensland therefore emerges as a hybridized version of international schooling, intensive second language teaching and a site of global competence focus, both in terms of language and intercultural skills, and the use of new media literacy skills. The following section presents a closer look at one sample site, and research findings from interviews with students and teachers involved in this selected immersion program in Queensland. The outcomes of the programs include an increased engagement with selected global competencies, which are constructed as identifiers by students positioning themselves as more globally aware than their mainstream cohort. A Sample Site The research took place at a German immersion program in Brisbane and involved interviews with five teachers (Teacher 1-5) and 15 students (Student 1-15) in Year 10 in June 2009. The interviews took place in informal settings between lessons, at lunchtime and in one designated lesson. An analysis of the interview data revealed that students created an identity around being immersion participants that can best be described as advancing Reimers’ (2009) knowledge of world issues as one dimension of global competencies. One student put it this way: Sometimes, we learn a lot more about world issues, also German issues; we chat about what we did in class afterwards in the playground and often notice that the other students don’t really know anything about these topics. (Student 1) This general impression was supported by other students’ statements, for example by saying “We seem to talk more about stuff happening in Germany, in Europe” (Student 2). In this German A LIVED CURRICULUM IN TWO LANGUAGES 9 immersion program, students singled out several obvious topics: “Things about the war”, “The Berlin Wall” (Students 7,8 and 9), “German films”, the international film festival “Berlinale” in Berlin (Student 2). This data not only supports Kramsch’s argument that in and through another language students discover subjectivities that will shape their lives (2009, p. 3), but also Pinar’s call for curriculum as an intellectual project of understanding (2003, p. 30). In response to terrorism threats and a focus on risk avoidance (Beck, 1992), the 21st century has seen a retreat from pluralism and ambivalence. Curriculum needs to re-establish spaces for pluralist and intellectually challenging perspectives, and the cultural differences that surface in immersion programs might just be such a space. It also became clear in the interviews that there was a substantial degree of interdisciplinarity and language and content-faculty collaboration. Students and teachers reported that they often cover the same topic in German language studies and the SOSE classroom, in particular when outside events like the Festival of German Film prompted an engagement with a specific topic. As part of an excursion to see a suitable film at the film festival, students would be engaged in topical explorations around the film, often involving topics such as the Berlin Wall or life after the reunification (popular German film themes). As part of their deeper engagement with world issues, some students constructed a new identity for themselves. Based on being immersion students and the extended issues they discussed, some students made comments like “Sometimes I feel smarter”(Student 4) or “I think we are more mature” (Student 8) or “The kids in the class are a bit smarter” (Student 7). This interesting synergy of individual and collective identities, this “We” that many immersion students subscribe to, indicates a new space, a ‘third culture’ almost, based on language skills, intercultural knowledge or at least interest, and a global engagement not understood as ‘mainstream’. The Melbourne Declaration of Educational Goals for Young Australians states that “global integration and international mobility have increased rapidly in the past decade (Ministerial Council of Education, 2008), and that these developments heighten the need to nurture a sense of global citizenship among young Australians. One concrete measure towards such a goal are school exchange programs, often a staple part of immersion programs. Indeed, one of the biggest areas of curriculum A LIVED CURRICULUM IN TWO LANGUAGES 10 extension for the interviewed cohort seems to have been their engagement with student exchange partners from Germany. On the one hand, this took place in a very practical way, by being exposed to German rock and pop music through sharing mp3-files and other electronic sources, on the other hand this extension was a longer process based on German students inviting their Australian counterparts to join in a social networking site called “Schülerverzeichnis” which is administered by and only open to school students by invitation. This once exclusively German site is now being used amongst Australian students who invite each other to join. The site is only available in German. In a truly globalised networking practice, Australian immersion students are engaging with the possibilities and repertoires of new technologies, while building up communication skills across cultures and languages. This extracurricular engagement with new media tools was also prevalent when interviewees talked about the use of websites as a source of information. Both teachers and students mentioned a large number of German-speaking websites which they frequently use. “The decision to use (or not to use) textbooks” (Stoller, 2004, p. 267) is often taken out of teachers’ hands, as the Queensland curriculum specifies content that is not available in predetermined target language textbooks. Teachers therefore choose to engage with online resources as the only way to plan and develop appropriate materials. Amongst the online resources mentioned in the present research were translation sites such as LEO (most students) and Blinde Kuh (most students) but also the German versions of familiar online sites such as Youtube, Google and Wikipedia (most students and teachers). The data suggest that within this sample immersion program the use of new media in a second language is a necessary activity for the whole cohort. Given their engagement with German social networking sites and their regular access to websites in German, these students have become ‘produsers’ (producers and consumers) (Bruns, 2008) of texts as emerging bilinguals, thereby approaching global competencies in language skills and engagement with social and cultural phenomena beyond their own immediate discursive environments. While this section has only presented a small section of the investigation and analysis of this immersion program and immersion education in Queensland, the scope and focus of the paper limits A LIVED CURRICULUM IN TWO LANGUAGES 11 the extent that can be covered here. A full report and analysis will follow in a future publication. The next section will now investigate possibilities and challenges if the whole immersion cohort is indeed the whole school, with a new and unique curriculum, merged from a local and an international curriculum. This section is based on Kate Sutherland’s ethnographic reflections on processes involved in merging the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) with the French primary curriculum in her role as Deputy Principal at Telopea Park School (TPS) in Canberra. Telopea Park In our capital city, by nature a destination for global nomads, a bilingual immersion program exists at Telopea Park School / Lycée franco-australien de Canberra (TPS) where English and French are the languages of instruction in the primary school bilingual program, with an option to continue in the high school (Lycée). Similar to the Middle Years programs in Queensland, the program utilises the curriculum to develop second language capabilities at the same time as delivering content, but is based on an inter-government ‘Cultural Agreement’ to meet the educational requirements of both the French and Australian Governments. While this particular agreement only concerns one Australian school, supranational agreements about schooling, for example within the OECD member countries, are one manifestation of globalisation (Henry, Lingard, Taylor, & Rizvi, 2001). There are therefore significant differences from the Queensland model which is based on only one state curriculum and does not respond to the interests of other national or sub-national systems. An examination of the design and articulation of the curriculum here sheds light on the reasons for the successful integration of TPS’s bilingual immersion program into the educational landscape of the ACT (ACT Government, 2004). The analysis draws on qualitative data and document analysis. Personal reflections from my extended experience in a leadership position in this setting, with particular responsibility for ‘harmonising’ the French and Australian curricula, along with document analysis are the major data sources. Documents created via bicultural collaboration and co-operation are germane to understanding this bilingual immersion program‘s curriculum and global imagination. The Context and the Cultural Agreement Aligning with the goals of the Agence pour l’Enseignement du Français à l’Etranger (French Agency for the Teaching of French Overseas), TPS is a binational and bicultural government school A LIVED CURRICULUM IN TWO LANGUAGES 12 established through an intergovernment agreement in 1983 (Commonwealth of Australia, 1983). France, like many other nations, competes in a language and culture ‘market’ often constructed as overrun by an Americanisation and Mcdonaldisation (Rizvi & Lingard, 2000) of social and cultural values. One of the goals of the French Agency and TPS is therefore to provide a progressive bilingual immersion program fostering French language and culture from kindergarten level onwards. Unique as a vision for education in Australia, students are expected to be literate and numerate in both languages at the conclusion of Year 6, based on a harmonisation or merging of French and Australian curricula requirements, Kindergarten to Year 6 / Grand Section à Sixième (Telopea Park School, 2009). Australian families accessing such a school model respond to global forces which individualise economic chances and often suggest linguistic capital as an important part of staying competitive worldwide (English, 2009). Campbell et al. (2009, p. 27) have pointed out that school choice is clearly influenced by such global forces: Emerging from the old and new middle class, there is a group of cosmopolitan parents who believe that they understand the changing nature of Australian and global society and economy. They are preparing their offspring to be adaptable and flexible along with inculcating new skills and humanist values. Students who attend the primary school are mainly from Australian families, but within these there is an increasing minority where English is not the first language in the home. The school enrolment policy stipulates that French nationals have priority enrolment status. Consequently, there are growing numbers of French nationals, resident in Australia, who are opting to enrol their children. Francophone families and students who have had exposure to the French curriculum or French immersion programs elsewhere are enrolled if spaces permit. Economic or diplomatic ‘Global nomad’ families, many of whom utilise the global system of French School Abroad, seek to enrol their children. Therefore, the K-6 student population is a rich linguistic amalgam in an international setting, providing a dynamic and developing space for ‘third cultures’ and transnational social fields. The current whole school student population (Kindergarten to Year 10) is approximately 1100 students, with over 400 in the K-6 program. The teaching staff of 100 includes 35 French nationals staffed by the French Agency, in an explicit attempt to foster collaboration and a merging of expertise A LIVED CURRICULUM IN TWO LANGUAGES 13 across teachers from Australia and France (ACT Department of Education, 2007a; Collard & Noremore, 2009; Department of Education Science and Training, 2005). As part of the Cultural Agreement, these teachers from France are recruited for up to four years to work with their Australian counterparts to plan and deliver the merged program. Therefore, each class has an Australian and a French teacher, both of whom are responsible for the children’s welfare and their learning. French national curriculum documentation is available for teacher reference, including online resources. As well as extensive access to English resources, French student texts, workbooks and exercise books are imported from France to support the delivery of the French components of the curriculum, including cursive handwriting. A professional translator undertakes day-to-day translations such as newsletters, parent correspondence, and student welfare and management documents. Both the ACT curriculum framework Every Chance to Learn (ACT Department of Education, 2007b)) and the French curriculum framework are available in French/English translations to support the curriculum merging process. The widespread use of common print languages has been identified by Benedict Anderson as instrumental in establishing a sense of belonging to an imagined community (Anderson, 1983), here a ‘third space’ imagined community of French speakers in Australia. The maintenance of such an institutionalised cultural and linguistic transnational field requires sustained time and resource commitment. To maximise the early development of French language in an English speaking community, students in Kindergarten, Year 1 and Year 2 have four days in French instruction and one in English (80:20 split). By Year 3, students have developed basic French literacy. They then have 50:50 English/French instruction from Year 3 to Year 6, including bilingual lessons, when teachers and students are expected to switch from one language to the other. Design of the Harmonised Curriculum The concept of harmonisation describes the merging of Australian and French curricula to facilitate the delivery of a bilingual curriculum as well as requirements of both governments. Curriculum harmonisation is completed within the school and involves the whole teaching team but principally myself, as the Australian Deputy Principal, the French Conseiller pédagogique and an A LIVED CURRICULUM IN TWO LANGUAGES 14 Australian executive teacher. These meetings develop a new form of habitus (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1977), allowing the participants to cope with a range of cultural differences inherent in two different curriculum visions. At Telopea Park, this active participation in creating a transnational space often results in the “cosmopolitanization of attitudes and values” (Mau, Mewes, & Zimmermann, 2008, p. 17) and an acknowledgment of commonalities previously unknown. Appadurai’s “flows along which cultural material may be seen to be moving across national boundaries” (Appadurai, 1996, p. 33) takes shape in this ‘harmonisation’ of French and Australian curricula with the help of people, resources and educational ideals. Both the French and ACT governments have renewed curricula in recent years. In the ACT, the Every Chance to Learn curriculum framework identified new requirements around essential content and 25 Essential Learning Achievements (ELAs) or overarching outcomes. The French government set out broad new curricula directions in Common Base of Knowledge and Skills (c) and in Le BO Numéro Hors Série Horaires et programmes d’enseignement de l’école primaire (French Department of Education Official Bulletin, 2008). From these major documents, the merged curriculum structure has been designed around ACT curriculum policy requirements but, using colour coding, identifies both French and Australian requirements, as well as content taught bilingually. Both frameworks define the scope of what is to be learnt in compulsory years of schooling identify what the nation sees as important to learn for the 21st Century have overarching outcomes to be achieved (The French “Pillars” and ACT Essential Learning Achievements) prioritise literacy and numeracy, science, civics, and information and communication technology highlight the importance of understanding French and Australian cultures have a focus on developing lifelong learning skills and competencies believe in the development of the affective domain recognise that our countries exist in interrelationship with others A LIVED CURRICULUM IN TWO LANGUAGES 15 The curriculum includes all the ACT Essential Learning Achievements (ELA) and French competencies. In this merged curriculum, there is no Language Other Than English (LOTE) organiser because French is a medium of instruction and the bilingual program itself is seen as meeting the requirements for ELA 15 -The student communicates with intercultural understanding. In addition, since students develop literacy in both French and English there is a combined Literacy curriculum organiser. A summary of the curriculum organisation and the language of instruction follows: Literacy (via both French and English) Numeracy (the majority of content is via French with about 25% via English) Social Science (via English) or Histoire / géographie et éducation civique (via French) Science and Technology (via English with some French) Physical Education (via French) and Health (via English) Arts – Music (via English), Visual (via French and English), Dance (via English) The following diagram provides an overview of the articulation of the curriculum with classroom processes at TPS. The diagram illuminates how the envisaged global competencies of linguistic skills and cross-cultural engagement must necessarily be structured by (two) strong local requirements for standardized testing and benchmarking. This ‘formalization’ of bilingual education, however, seems to secure successful implementation and delivery of such an ambitious transnational project: A LIVED CURRICULUM IN TWO LANGUAGES 16 Articulation of the Curriculum with the Classroom (see Figure 1) Articulation of the K-6 Curriculum Preamble This describes the K-6 context, the relationship between Every Chance to Learn & Le socle commun de connaissances et de compétences, bilingualism, harmonisation . It includes the K-6 curriculum ‘organiser’ and the French- Australian class structures. Scope and Sequence Documents Social Science Literacy Science and (French and Numeracy Technology The Arts English) (including histoire géographie et éducation civique) Physical Education & Health Interdisciplinary ELAs 1-6 and French competences are integrated across organisers Overviews Overviews are the articulation of the scope and sequence documents at year level, K-6. Overviews are created by year teams each semester to meet the needs of the students. They include agreed elements such as: differentiation of curriculum, bilingual and harmonised activities, LA, ESL and gifted and talented. Units of Work Each teacher designs a learning program for their class(-es). They will decide on pedagogical approaches and assessment tasks for their students. Results of Evaluations Nationales, PIPS and NAPLAN inform planning to meet the needs of all students. Assessment and Reporting Teachers assess according to the outcomes identified in the overview. They use several tools to assess the students. Work samples assist teachers in year teams to establish standards across classes. Student achievement is reported through the year via Learning Journeys, Parent-Teacher Interviews, Outcome and A-E Reports, PIPs and NAPLAN reports. Articulation of the Curriculum, K-6, Figure 1 A LIVED CURRICULUM IN TWO LANGUAGES 17 The dynamic nature of new transnational practices results in classroom activities being a mix of French and Australian approaches, dependent on situations, resources and the teachers’ own subjectivities. In French classrooms the activities tend to follow French guidelines as stipulated by the French Inspector, and in Australian classrooms activities are constructed towards Australian guidelines, namely, the ACT Quality Teaching model which was adopted from the NSW model (NSW Department of Education and Training, 2006). In general, the curriculum is delivered through integrated units by Australian staff where one component of the organiser, for example Social Science, would be used as a vehicle to deliver Literacy, Numeracy and other essential content. In bilingual classrooms and specific projects, where both teachers are present, activities are an agreed blend of the two approaches, creating transnational pedagogical fields. The need for outside classroom use of the two languages (LoBianco, 2009, p. 34) to enable transnational social fields for the bilingual students at TPS is met in several different ways. Students are provided with many opportunities to use each language away from the classroom. School-wide, there are bilingual signs, teachers speak their mother tongue to students, and correspondence is regularly bilingual. Other opportunities include bilingual assemblies, sports days, public speaking competition, camps, library and the annual concert. Examples are: Year 4 Thinking Carnival / Festival de la Pensée Kindergarten’s Teddy Bears’ Picnic at the Australian National Botanic Gardens Francophonie Week activities French exhibitions at Alliance Française de Canberra These activities are part of Telopea Park’s desire to create a new imagined transnational community for the whole school. The Thinking Carnival, for example, is an annual Year 4 event that uses constructivist theories of learning, including cooperative learning techniques, in a bilingual environment. In a highly structured day, students are set challenges to which they have to propose a creative solution. In an out-of-classroom environment, students are expected to read, write and speak in both French and English. Teacher preparation notes from the Thinking Carnival organisers were A LIVED CURRICULUM IN TWO LANGUAGES 18 translated into French, which allowed French staff also to add their positionalities to its rationale and educational purpose, resulting in transnational repertoires unique for the Telopea Park setting. Conclusion In Appadurai’s vision of modernity, the nation-state is dissolved and cultural landscapes are instead characterised by a fragmented, imaginary world (Appadurai, 1996). We have come to the conclusion that immersion education in Australia begins to appropriate this new vision of modernity and create a new public sphere that unites diasporic, ‘native’ and transitory cultures in new sites for global imagination. The call for global linguistic and intercultural competencies can only be embodied in such local policies and initiatives. As Burawoy points out, these global “connections and flows are not autonomous, are not arbitrary patterns crossing in the sky, but are shaped by the strong magnetic field of nation states” (2000, p. 34). The analysis of the two case studies has pointed to potentials for this teaching approach beyond isolated and small-scale programs, envisaging bilingual education as a widespread approach to encourage the engagement of Australian students (both local tribes and global nomads) with sustained transnational social fields. Globalisation flows produce students who have diverse affiliations with the language they are learning and the schooling cultures they are attached to (Mitchell & Parker, 2008). Their diverse linguistic, cultural and personal life-worlds need to be recognised in the provision of flexible pathways of schooling in Australia, acknowledging the importance of their lived experiences. One aspect that emerges in both Queensland and at Telopea Park is the role of bilingual immersion for ‘third culture’ or ‘global nomads’ students with a heritage or background language other than English. Telopea Park clearly identifies French native speakers as part of its intended cohort. However, native, heritage or background speakers seem to be drawn to some of the second language immersion programs in Queensland as well. A further step would be to investigate a potential role for immersion programs as a provision for heritage speakers to receive part of their education in their home language. This study is therefore significant for policy makers and school administrators who are interested in responding to global connections and global imaginations by providing visionary pathways of schooling locally. A LIVED CURRICULUM IN TWO LANGUAGES 19 There is a ‘whiff’ of the Big Wide World discernible in immersion programs, an engagement with transnational social fields often muted in monolingual settings. The 21st century will require skills and dispositions of Australian students that allow them to participate in working towards global solutions for global challenges. Language skills and a positive disposition to engage with other cultures will be central to such participation. We believe that engaging with curriculum through the lens of two different languages presents one way towards cosmopolitan cultural competences, including “openness towards difference and otherness” (Roudometof, 2005, p. 122). Immersion programs allow for new subject possibilities for all Australian students, based on their engagement with transnational social fields through shared mediascapes on social networking sites and ‘third places’ in their own cultural positionalities. Finally, it is also important not to lose sight of one of the main aims of bilingual or immersion education in Australia. These programs are amongst the most promising designs to address the marginalized position of second language learning in Australia. Their bond to key learning areas, their ability to slot into existing mainstream school structures and their stated interest in other cultures and languages is one of Australia’s best opportunities not to miss the ‘globalisation train’ in terms of linguistic and intercultural skills. References Abowitz, K. K., & Harnish, J. (2006). Contemporary Discourses of Citizenship. Review of Educational Research, 76(4), 653-690. ACT Department of Education. (2007a). ACT Educational Leadership Framework. Canberra: ACT Department of Education. ACT Department of Education. (2007b). Every Chance to Learn. Canberra: ACT Department of Education. ACT Government. (2004). ACT Education Bill. Canberra: ACT Government. Aldridge, J., & Christensen, L. (2008). Globalization and Education. Childhood Education, 85(1), 64-66. Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined Communities - Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso. Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at Large. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. A LIVED CURRICULUM IN TWO LANGUAGES 20 Beck, U. (1992). Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage. Berthold, M. (1995). Rising to the bilingual challenge. Melbourne: NLLIA. Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and Symbolic Power (G. Raymond & M. Adamson, Trans.). Cambridge: Polity Press. Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J.-C. (1977). Reproduction in education, society and culture. London: Sage. Brooks, R., & Waters, J. (2009). International higher education and the mobility of UK students. Journal of Research in International Education, 8(2), 191-209. Bruns, A. (2008). The Future Is User-Led: The Path towards Widespread Produsage. Fibreculture (11) Retrieved March 5, 2010, from http://eleven.fibreculturejournal.org/fcj-066-the-future-is-user-led-the-path-towardswidespread-produsage/. Burawoy, M., Blum, J. A., George, S., Gille, Z., Gowan, T., Haney, L., et al. (2000). Global Ethnography: Forces, Connections, and Imaginations in a Postmodern World. Berkeley: University of California Press. Campbell, C., Proctor, H., & Sherington, G. (2009). School Choice: How Parents Negotiate The New School Market in Australia. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin. Collard, J., & Noremore, A. (2009). Leadership and Intercultural Dynamics. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing. Commonwealth of Australia. (1983). Australian Treaty Series 1983 No. 8. Agreement between the Governments of Australia and the Government of the French Republic concerning the Establishment of a French-Australian School in Canberra. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. Cooper, G. (2008). Assessing International Learning Experiences: A Multi-Institutional Collaboration. Phi Kappa Phi Forum, 88(1), 8-11. Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (2000). Introduction: Multiliteracies: The beginnings of an idea. In B. Cope & M. Kalantzis (Eds.), Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures (pp. 3-8). New York, NY: Routledge. de Courcy, M. (1997). Benowa High: A decade of French immersion in Australia. In R. K. Johnson & M. Swain (Eds.), Immersion: International Perspectives (pp. 44-62). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. de Courcy, M. (2002). Immersion Education Downunder. The American Council on Immersion Education (ACIE) Newsletter, 5(3), 1-4. Department of Education Science and Training. (2005). Australian Government Quality Teacher Program Getting Started with Intercultural Language Learning: A resource for School. Canberra: Department of Education Science and Training. Dobrenov-Major, M. (1998). Impact on Students of the German Immersion Program at Kenmore State High School, Brisbane and the Implications for the Development of Immersion Mode of Teaching in Australia. Pacific-Asian Education, 10(1), 7-22. Education Queensland. (2007). Immersion Program Information Handbook. Retrieved March 12, 2010, from http://education.qld.gov.au/curriculum/area/lote/immersion.html. English, R. (2009). Selling Education Through "Culture": Responses to the Market by New, Non-Government Schools. Australian Educational Researcher, 36(1), 89-104. Fox, C. (2007). The Question of Identity from a Comparative Education Perspective. In R. F. Arnove & C. A. Torres (Eds.), Comparative Education: The Dialectic of the Global and the Local (3rd ed., pp. 117-128). Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield French Department of Education Official Bulletin. (2008). Teaching Hours and Programs for Primary School. Paris: French Government. Garcia, O. (2009). Bilingual Education in the 21st Century. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. A LIVED CURRICULUM IN TWO LANGUAGES 21 Gargano, T. (2009). (Re)conceptualizing International Student Mobility: The Potential of Transnational Social Fields. Journal of Studies in International Education, 13(3), 331-346. Guerra, J. C. (2008). Cultivating Transcultural Citizenship: A WritingAcrossCommunities Model. Language Arts, 85(4), 296-304. Henry, M., Lingard, B., Taylor, S., & Rizvi, F. (2001). The OECD, Globalisation and Education Policy. Oxford: Pergamon. Hunter, W. D. (2004). Got Global Competency? International Educator, 13(2), 6-12. Kramsch, C. (2009). The Multilingual Subject. What language learners say about their experience and why it matters. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Lam, W. S. E. (2006). Culture and Learning in the Context of Globalization: Research Directions. Review of Research in Education, 30, 213-237. Lambert, R. (1996). "Parsing the Concept of Global Competence," Educational Exchange and Global Competence. New York: Council on International Educational Exchange. Langford, M. (2001). Global Nomads, Third Culture Kids and International Schools. In M. Hayden & J. Thompson (Eds.), International Education: Principles and Practice (pp. 28-43). London: Kogan Page. LoBianco, J., Liddicoat, A. J., & Crozet, C. (Eds.). (1999). Striving for the Third Place: Intercultural Competence through Language Education. Melbourne: Language Australia. LoBianco, J. (2003). Culture: visible, invisible and multiple. In J. Lo Bianco & C. Crozet (Eds.), Teaching Invisible Culture: Classroom Practice and Theory (pp. 11-38). Melbourne: Language Australia. LoBianco, J., & Slaughter, Y. (2009). Australian Education Review: Second Languages and Australian Schooling. Camberwell, VIC: Australian Council for Educational Research. Mau, S., Mewes, J., & Zimmermann, A. (2008). Cosmopolitan attitudes through transnational social practices? Global Networks, 8(1), 1-24. Ministerial Council of Education, E., Training and Youth Affairs (MCEETYA). (2008). Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians. Melbourne: MCEETYA. Mitchell, K., & Parker, W. C. (2008). I pledge allegiance to.... Flexible citizenship and shifting scales of belonging. Teachers College Record, 110(4), 775-804. Modern Language Teachers Association of Victoria (Producer). (2009). MLTAV 2009 National Curriculum Survey Statistical Results. Retrieved February 17, 2010, from http://mltav.asn.au/images/documents/MLTAV_09_National_Curriculum_Survey_Re sults%20Final.pdf NSW Department of Education and Training. (2006). NSW Quality Teaching Model. Retrieved February 22, 2010 from https://www.det.nsw.edu.au/proflearn/areas/qt/qt.htm Pinar, W. F. (Ed.). (2003). International Handbook of Curriculum Research. Mahwah, N.J. : L. Erlbaum Associates. Reimers, F. (2009). Global Competency: Educating the World. Harvard International Review, 30(4), 24-27. Rivza, B., & Teichler, U. (2007). The Changing Role of Student Mobility. Higher Education Policy, 20, 457-475. Rizvi, F., & Lingard, B. (2000). Globalization and Education: Complexities and Contigencies. Educational Theory, 50(4), 419-426. Roudometof, V. (2005). Transnationalism, cosmopolitanism and glocalization. Current Sociology, 53(1), 113-135. A LIVED CURRICULUM IN TWO LANGUAGES 22 Smala, S. (2009). New literacies in a globalised world. Literacy Learning: The Middle Years, 17(3), 45-50. Spring, J. (2008). Research on Globalization and Education. Review of Educational Research, 78(2), 330-363. Telopea Park School. (2009). K-6 Harmonised Curriculum Preamble. Canberra: Telopea Park School. Tikly, L., & Crossley, M. (2001). Teaching Comparative and International Education: A Framework for Action. Comparative Education Review, 45(4), 561-580. Tisdell, M. (1999). German Language Production in Young Learners Taught Science and Social Studies through Partial Immersion German. Babel, 34(2), 26-32. Vertovec, S. (2009). Transnationalism. London: Routledge.