aristotle`s overall project

advertisement

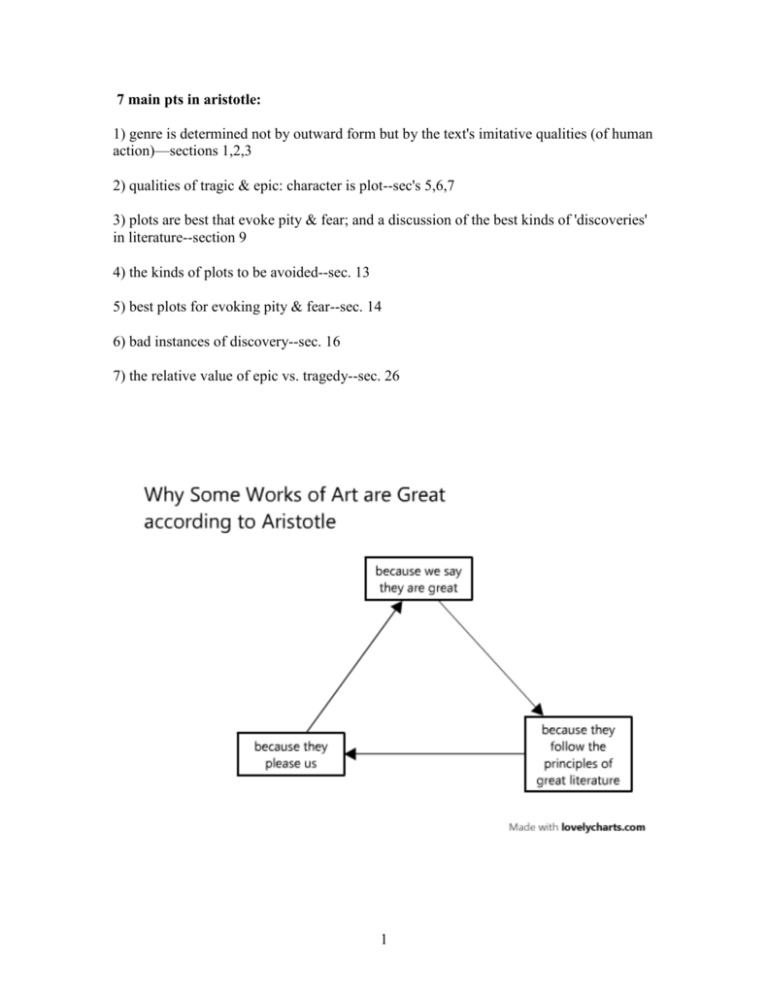

7 main pts in aristotle: 1) genre is determined not by outward form but by the text's imitative qualities (of human action)—sections 1,2,3 2) qualities of tragic & epic: character is plot--sec's 5,6,7 3) plots are best that evoke pity & fear; and a discussion of the best kinds of 'discoveries' in literature--section 9 4) the kinds of plots to be avoided--sec. 13 5) best plots for evoking pity & fear--sec. 14 6) bad instances of discovery--sec. 16 7) the relative value of epic vs. tragedy--sec. 26 1 Aristotle’s project in The Poetics, C. Brown Description: By Aristotle’s time the Greeks had been on a knowledge-seeking quest for about 200 years, to distance their knowledge from explanations dependent upon magic. Thus, Aristotle’s project in The Poetics, as in all of his treatises, is to establish a body of knowledge about what is real based on a firm, rational epistemology, and he was convinced as Plato was before him that these two branches of philosophy, epistemology and ontology, are ultimately one. This confluence of epistemology and ontology works for Aristotle as follows: there exists between the world and our knowledge of it a possible fit, so to understand what something is, is to understand how we know it, and vice-versa: to understand how we know something is to understand what that something is. Knowledge is knowledge of what is real, and accordingly what is real is that which we know. We modern, psychologized folk have a hard time understanding this leap of faith these classical thinkers made; we tend to question all motives, especially our own. The earliest writer we recognize as articulating this doubt is Shakespeare, in Hamlet, but more recently, especially its terrifying aspects, Nietzsche, Kafka, Dostoevsky, and Freud, and in America Poe. But for Aristotle, that “fit” of our thoughts about the world on the one hand and the world itself on the other was an exhilarating philosophical foundation for a revolutionary understanding of the world and our place in it. But his concept of what is real is different from Plato’s, and thus his concept of knowledge is different. He agreed with Plato that things have essences, but these essences for him can be found by studying the thing itself and other things of its like; the things in this world are real, not just copies of the ultimate Form of the thing, as Plato believed. In fact, the abstract Form of the thing, which Plato revered as the highest reality, for Aristotle simply goes away when we come to know the physical thing itself. In this way his project is much closer to contemporary science than anyone before him, though the deductive aspect of it prevents it from being truly modern (modern science of course has a deductive element to it as well, it’s just not advertised as much). So, in an effort to find the essence of a thing, Aristotle must find not just a list of that thing’s characteristics, but a list of its qualities that are inherent in the thing itself and thus determinate of its nature, those attributes whose absence would entail the thing’s nonexistence. Socrates was fat and bald, but were those attributes essential to his nature? If he weren’t fat and bald, would he still be Socrates? Yes, but not if he stopped seeking knowledge. So being fat and bald are not essential aspects of Socrates, but seeking knowledge is, as Aristotle believed it was for all humans. Thus the nature and purpose of Aristotle’s book Poetics: to categorize literature’s essential qualities and characteristics for the purpose of determining what literature is, and to establish those qualities and characteristics as necessary for all future instances of it. So the definitions in the Poetics are not merely convenient categories or divisions, and nor are they merely descriptions of the art after the fact; rather, they describe for him what is essential to the art in question, what is essential to its nature and thus an essential quality for any literature worthy of that label. This is also why the treatise is somewhat 2 dry to read: he’s not, ostensibly at least, making an argument; he’s not interested in presenting an inspiring text that argues for some noble role for literature; he’s merely creating a taxonomy of literature’s various types, for the sake of clarifying what literature’s essential qualities are. It’s a purely descriptive exercise, but one that he believes is important nonetheless, by clarifying those essential qualities that literature must have to fulfill its nature. As M. H. Abrams argues, this ontological inquiry of Aristotle’s—determining the essence of a work of art by detecting and categorizing its essential qualities—is what distinguishes Aristotle’s perspective on literature from Plato’s, in that it justifies the study of literature as literature, as more than just a divine or “psychological” artifact. But why would Aristotle—someone who believes that the be all and end all of being human is to be happy—promote the study of a particular human endeavor for its own sake? The answer is that he doesn’t. He believes that literature functions as a tool to help us achieve that happiness. Literature responds to two basic needs of ours: to be delighted and to know. Art is imitative, and we naturally take delight in imitation, just as we naturally yearn to know, to seek knowledge. Art functions to delight us in the process of giving us knowledge. But what does art give us knowledge of? Of how to be good, which ultimately provides happiness, as far as it is in our ability to attain happiness. Following these principles, art, which is naturally imitative, is imitative not of Plato’s abstract Forms, which would not help inspire us to live good lives. Plato’s Forms are too abstract, too much divorced from the real world around us, and thus too much divorced from the true essences of things. No, for Aristotle art is imitative of human action. But why action? Again, because it is consistent with his metaphysics (and his philosophy of happiness): he believed that the essence of each thing is its movement toward its purpose, which is to reach the form of itself, to “fulfill its own nature.” We label this philosophy teleology, from the Greek root tele-, from telos, meaning end or purpose. Furthermore, Aristotle felt that ultimately the purpose of everything was to help us humans achieve our ultimate purpose, which is to think and attain knowledge and become a good person and thus happy, by achieving a high level of self knowledge, to recognize ourselves as knowledge seekers and gatherers. The purpose of grass is to achieve grass-hood, a rabbit to achieve rabbit-hood, and both of these things are here on earth to help us achieve our ultimate purpose, our human-hood. (What, we might ask, are robins here for? since all things are here to help us achieve a higher form of goodness, then perhaps robins are here to achieve Robin Hood?) Thus art’s purpose is to show us ourselves in action, to reveal to us a picture of ourselves in the best of form, so to speak, so we can gain knowledge of how to be good and thus achieve that recognition of ourselves as knowers of ourselves. So art is imitative of human action, and human action follows the nature of things by virtue of its movement toward its own purpose. And thus drama and epic poetry are superior forms of art, for they quintessentially show us how to behave in a way that compels us toward our own good, self-knowing natures. We know this is true, according to Aristotle, because drama 3 and epic poetry please us, and since we are naturally pleased by imitative and instructive things, we know these things are good. Art imitates, and in so doing instructs us in how to fulfill our naturally inquisitive and moral natures, which, if followed, will make us happy. Critique: Our modern sensibilities detect a circular reasoning here, especially as this system has come to be ensconced in the neoclassical theory canon. We see that Aristotle’s philosophical system is used to extol the principles of great literature, literature that in turn is used to validate the principles upon which that literature is judged. The system goes something like this: Nature is a model of order to be imitated in art, nature being the process by which all things move to fulfill their own natures (including human action), and we are made to see that that imitation is successful because we see it working in the classics, works of art that in turn reinforce the prescriptions themselves. If nature is action, then literature that emphasizes action—say, drama or epic poetry, as opposed to, say, confessional lyrical poetry—is good because we observe that it pleases us. To highlight this circularity, we could argue that lovers of classical literature are probably pleased not by the literature per se, but merely by the way it matches their expectations of what literature should be, expectations created by prior attitudes about what nature is, attitudes which had been previously established to define great literature. We will see this critique again when we read Nietzsche. This Aristotelian system is the first justification for an empirical study of literature in Western thought, and one we’ve inherited. And I would argue that we don’t notice it much, if at all, as an imposed system, because the same logic has been used to justify what we now call scientific inquiry, and thus we take for granted this system’s epistemology. Here’s an explanation of the circular reasoning in the epistemology of science: We humans need, according to Aristotle, close descriptions of what determines any phenomenon (e.g., a tree’s essential “treeness”) to determine what that thing is, and we need to know what a thing is to believe we know it for what it is, but these qualities that we determine are essential to that thing are actually arbitrarily chosen—there’s no such thing as an essential quality of something; it’s essential qualities have been determined (unknowingly) merely to function as an element in the little system that we’ve told ourselves measures reality. It’s easy for us to lose sight of the significance of Aristotle’s epistemological/ontological system because we take for granted our expansive knowledge of the world, or at least what we determine as “the world,” or “what things are.” For the most part we don’t recognize the system—it has become invisible; in fact, its invisibility is the most powerful aspect of it. (We could argue that the greater psychological context for this system that makes us believe that we know things is that it is a product of our impulse to control the world around us; that would be a Nietzschean critique, since he believed that our desire for power is a fundamental one—he called it our Will to Power.) An easy example of how this system has indoctrinated us can be taken from our “understanding” of the significance of race, which is apropos to Aristotle since he was a 4 racist: traditionally, we don’t recognize that, say, a Hispanic person’s distinction from a Caucasian person is relatively arbitrary because we’ve internalized the knowledge-system that purports that that distinction is significant and therefore real. We’ve internalized it because that system has also taught us that, say, a strawberry is distinct from a wood chip, and we all know not to eat wood chips. But for whom is that distinction useful? A termite? (I’m assuming a termite would eat a strawberry if its life depended on it.) To carry out this inquiry, we would then ask, “For whom is the racial distinction useful?” We would have to conclude, the racist. Almost all of our knowledge, in fact, is based on a system that, in spite of the arbitrary categories that it purports as real, we have accepted as real simply because it is by way of these distinctions that we come to know the world, survive in it, and construct value systems that support our vision of our proper place in the world. This is how the epistemological systems are not merely academic, but provide our lives with meaning. How we know what we know explains why we know it. Of course post-humanists like making these kinds of systems visible again, usually by arguing that the systems are merely self-serving: phenomena are what we say they are merely because we’ve created this epistemological system so we can make the claim that phenomena are what we say they are. A tree’s “essence” determines what it is merely because we want that “tree” category to determine its identity. The “essence” of a poem or a story, or literature in general—whether it’s “a mirror of a mirror” (Plato); “a representation of human actions eliciting pity and fear” (Aristotle); “an overflow of emotion recollected in tranquillity” (Wordsworth); or “a reconciliation of opposite and discordant qualities” (Coleridge)—determines what a poem is, merely because that’s what we want it to be, presumably to support our own desires for the knowledge or power that that theoretical system confers. Since we’re making political inquiries in this unit, we might ask ourselves what political purposes are served that may have determined this epistemological system and its particular prescriptions for defining literature, for what it is and is not, and for what is and is not involved in the making of it. Does anyone gain something from the perpetuation of this invisible system? If so, who and what? For a post-humanist, denying universal human qualities and values, when Aristotle argues that the qualities that make literature great are the qualities that elicit certain emotions that he believes make a man (not a woman) a respectable man and a respectable Greek he is helping to create a standard that has less to do with literature than it does with politics: that standard functions primarily to support his Greco-centric, chauvinistic values. 5