The concluding movements of Bill Readings` The University in Ruins

advertisement

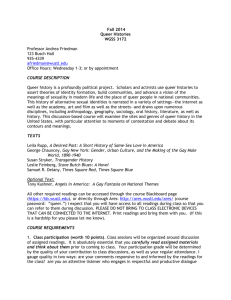

Mason 1 Derritt Mason CSCT 701 Dr. David Clark 18 April 2006 Queering the Ruins: Cultural Studies, Queer Theory, and the Future(s) of the University The concluding movements of Bill Readings’ The University in Ruins are riddled with provocative suggestions regarding the future of this crumbled institution. “We need to think about a community,” Readings argues, “in which communication is not transparent, a community in which the possibility of communication is not grounded upon and reinforced by a common cultural identity” (185). The university, he continues, “will have to become one place, among others, where the attempt is made to think the social bond without recourse to a unifying idea, whether of culture or of the state” (191). These are complex ideas that demand unpacking. Although cultural studies has been described by critics like Henry and Susan Giroux as the most promising discipline capable of imbuing students with the skills needed for social agency and active citizenry, there is nonetheless a general critical unease as to whether or not this contentious area of study is indeed an effective space for raising what Readings calls the crucial question of “being-together” (20). Some have accused cultural studies of becoming smugly complacent in a newfound positivism; Tilottama Rajan points to academia’s unfortunate dereferentialization of “culture,” which allows it to be treated as a “disposable, manageable subject” instead of a site of perpetual struggle and debate (“Wake” 72). To complicate these ideas, I suggest that cultural studies is further problematized by the emergence of its counterscience – queer theory – which points to cultural studies’ Mason 2 incompleteness while challenging the boundaries that divide the faculties. Moreover, I argue that just as queer theory succeeds in unsettling cultural studies, it can also provide myriad opportunities for rethinking the university as a community – or rather a community in ruins – and enabling critical analyses of pedagogy and the relationships between academic disciplines. Using the work of Deborah Britzman, I suggest that queer theory succeeds in rendering permeable the membranes dividing the faculties while troubling our understanding of how disciplines – and their disciples – relate to one another (80). In this paper, I call for the amorphous, provocative, and critical lens of queer theory to be used to both irritate the university and re-think how it works. My project will inevitably remain unfinished, “for queerness can never define an identity; it can only ever disturb one” (Edelman 17). Here, I attempt to disturb a variety of conversations about the university by bringing them into contact with queer theory; any number of these conversations could be taken up and expanded more broadly in other spaces. After mapping the emergence of queer theory from the interstices of cultural studies, I will consider how queer theory potentiates various theoretical notions of the university. First, I will turn to the importance of risk in the university and use Eve Sedgwick’s theorization of shame to destabilize the problematic connection between discipline and self. Queering Derrida’s idea of the rootless “professor at large,” I will further argue that queer theory allows us to imagine new academic relationships between professors, their disciplines, and the disciplines of their colleagues (135). I will conclude by unpacking Readings’ conception of the university as a “dissensual community” (127), a site that could allow an engagement with otherness devoid of identity, and proposing Mason 3 my own theoretical vision for the university: that of the neighbourhood. It is my hope that these queer ideas succeed in providing a new and complex theoretical lens for navigating Readings’ ruins. In the first half of his text, Bill Readings addresses the profound uncertainties surrounding the role of the university through a “structural diagnosis” of its perpetually shifting institutional function (2). He suggests that the university ceased to operate in a reciprocally protective relationship to the state as an “intermediate institution” dedicated to the cultivation of citizens who would produce and reproduce a certain national cultural identity (64). Culture, then, was freed from the ideological purpose of the university and could become an object of study in and of itself (Readings 64). “The idea of Cultural Studies arises,” Readings emphasizes, “at the point when the notion of culture ceases to mean anything vital for the University as a whole. The human sciences can do what they like with culture, can do Cultural Studies, because culture no longer matters as an idea for the institution” (94). Critical reports on the current state of cultural studies are conflicting, but it is clear that something has unsettled this discipline. In their Take Back Higher Education, Henry and Susan Giroux lament that “cultural studies as a field seems to have passed into the shadows of academic interests” (89). They see a great deal of promise in “discourses … that make culture itself the object of inquiry and critical analyses” (90-1). In “In the Wake of Cultural Studies,” Tilottama Rajan conversely argues that “far from being a spent force, Cultural Studies … has undergone a symbiosis with globalization, wherein its dereferentialization is what makes it dangerous to some of its own original components (70). For Rajan, the danger of cultural studies lies in “its teleology of ‘absolute self-transparency’ based on total communicability” (“Wake” 74); Mason 4 in other words, cultural studies presumes to entirely know and have the means to communicate the essence of “culture” in its myriad shapes and forms. Cultural studies “does not reflect on itself within a historical framework so as to recognize that there are other ways of thinking culture,” Rajan argues, “let alone interdisciplines that mediate humans’ relationship to their world differently” (“Wake” 72). An insidious positivism seems to have crept slowly back into a discipline that strove, at its roots, to challenge those aspects of culture that present themselves as unquestionable truth. In many ways, the Girouxs’ text seems symptomatic of this tendency toward what Derrida terms a problematic form of “end-oriented research … that is programmed, focused, organized in an authoritarian fashion in view of its utilization” (141). The Girouxs’ allergy to a cultural studies that would be “simply deconstructive” (108) coupled with their proscriptive enumeration of projects wherein academics “will have to focus their work on the immediacy of more public problems that are relevant to important social issues” (114) bespeaks a view of culture that is necessarily translatable to a specific left-wing politic. This it not to undermine the important work the Girouxs have done in confronting the pervasiveness of oppressive neoliberal and neoconservative ideologies in the academy, but rather to highlight the way culture, dereferentialized, can be appropriated and wielded with the very presumed manageability that Rajan indicates. Although the Girouxs identify their vision of democracy as “an ongoing project, always and necessarily unrealizable” (17), their brand of cultural studies does not seem to include the self-reflexivity of a discipline aware of its “always-already-incompleteness” (Rajan “University”). Mason 5 In The Order of Things, Michel Foucault outlines the emergence of countersciences alongside the human sciences they endeavour to emulate and critique. Countersciences, described by Rajan as “dangerous intermediaries” in the field of knowledge, point to the perpetual incompleteness of the human sciences by exposing the latter’s need to be supplemented and irritated by other discourses (“University”). “Above [or interwoven with] ethnology and psychoanalysis,” Foucault argues, the counterscience of linguistics emerges “to traverse, animate, and disturb the whole constituted field of the human sciences” (381). He continues: [Linguistics] would make visible, in a discursive mode, the frontier-forms of the human sciences; like them, it would situate its experience in those enlightened and dangerous regions where the knowledge of man acts out, in the form of the unconscious and historicity, its relation with what renders them possible. In ‘exposing’ it, these … countersciences threaten the very thing that made it possible for man to be known (Order 381). Just as Foucault argues that linguistics troubles the very substance that makes knowledge about psychoanalysis and ethnology ostensibly knowable (thus challenging the exhaustiveness and boundaries of the disciplines themselves), I claim that queer theory points to the forever-incompleteness of cultural studies. Contrary to Bill Readings, who believes that “the radicalism of queer theory risks being an academic one, designed to render queer theory susceptible to introduction across the curriculum” (211), I argue that the radical potential of queer theory stems from its demand, like that of Reading’s “University of Thought,” that we “ask what it means, because its status as a mere name – radically detached from truth – enforces that question” (160). In what follows, I will Mason 6 examine how queer theory, through its constant problematizing of dyadic notions of gender and sexuality, may also succeed in troubling our understanding of academic discipline (especially cultural studies) and the relationships between university faculties. What some might consider a problem with queer theory from the outside – its untranslatability and call for open-ended questioning – is its primary strength from the inside. In “Gender Criticism,” Eve Sedgwick traces the development of queer theory as “an alternative analytic axis” (276) that “[maps] the fractal borderlines between gender and its others” (273). In other words, queer theory points to that which exceeds discourses of gender; it challenges gender studies to recognize its own incompleteness by positioning sexuality as “the first other of gender” (Sedgwick “Gender” 273). Sedgwick rightly observes that Foucault’s groundbreaking work on sexuality did not “[issue] in a new movement of ‘sexuality criticism.’ Rather, its strongest effects have been radically partial – partial enough, perhaps, even to call into question the mapping of that neatly unified ‘sexual’ field” (“Gender” 281). In other words, queer theory emerged with the theoretical capacity to question the completeness of academic taxonomies. Queer theory, then, can point to the limits of cultural studies in ways that “sexuality criticism” never could. Deborah Britzman similarly argues in “Queer Pedagogy and Its Strange Techniques” that queer theory “takes up that queer space of simultaneously questioning and asserting representations and outing the unthought of normalcy. The attempt is to provoke yet-to-be-made constructions of subjects interested in confronting what Peggy Phelan terms as ‘the not all’ of representation” (82). Normalized discourses, characterized by Britzman as “unthought,” are challenged by queer reading practices, which “[constitute] the criteria that make the self and that make another both intelligible Mason 7 and unintelligible, an occasion for thought to think against itself” (94, my emphasis). This excess of thought, disregarded by a cultural studies that flirts with transparency and disciplinary closure, is exposed by a queer pedagogy that “[requires] something more than the self in order to think the self differently … to [think] ‘beyond one’s means’” (Britzman 92-4). In other words, the recognition that there is always an excess to thought allows an openness to other pedagogical practices and understandings of self and other that bear greater creative potential than discourses that presume-to-know. I am interested in the idea that queer theory can challenge thought itself – how can it go about doing this, and why it is important to understanding and re-thinking the university? I suggest that a queer reading of the university shares much with Readings’ call for the “University of Thought” to replace the current corporatized “University of Excellence” (145) in that both “thought” and “queer” are self-consciously open signifiers. “Thought, unlike excellence, does not masquerade as an idea,” argues Readings; “in the place of the simulacrum of an idea is the acknowledged emptiness of the name – a selfconscious exposure of the emptiness of Thought that replaces vulgarity with honesty” (160). He proceeds to suggest that “Thought does not function as an answer but as a question,” an invitation to ask what exactly “Thought” signifies (160). Jacques Derrida similarly articulates this responsibility to Thought as the act of “[rendering] reason,” or the duty “to respond to the call of the principle of reason” (136). “Thought”’s intentional resistance to concretization is in itself rather queer; as Britzman argues, “queer theory transgresses the stabilities of the representational,” constantly challenging that which would represent itself as a wholly closed and fixed subject (80). Britzman envisions a queer pedagogy that “worries about and unsettles normalcy’s imminent exclusions, or … Mason 8 normalcy’s ‘passions for ignorance’” (80) and raises the important question: “Can a queer pedagogy implicate everyone involved to consider the grounds of their own possibility, their own intelligibility, and the work of proliferating their own identifications and critiques that may exceed identity as essence, explanation, causality, or transcendence?” (81). This work of self-critique and self-exceeding could be differently articulated as Readings’ responsibility to answer Thought or Derrida’s call to render reason, but I believe that these ideas must be pushed even further. Thinking is a type of risk, it seems, in that it forces us to question not only our own subjective positioning but also how we come to understand ourselves in relation to who we perceive as our academic others. I argue that our existence as academic subjects is contingent on the creation of outsiders – the positioning of academic others opposite ourselves in a disciplinary binary. To be productive cultural theorists in the Girouxs eyes, for example, we must not be narcissistic and shallow deconstructionists. When the constructedness of these arbitrary academic subjectivities is put into question – or queered – we begin to think, as Britzman suggests, against thought itself (94). “When pedagogy meets queer theory and thus becomes concerned with its own structure of intelligibility,” Britzman argues, “the very project of knowledge and its accompanying subject-presumed-to-know become interminable despite the institutional press for closure, tidiness, and certainty” (82). Re-thinking subjectivity is a risk that, as theorized by Mary Zournazi and Isabelle Stengers, “is the difference between probability and possibility. If we follow probability there is no hope, just a calculated anticipation authorized by the world as it is” (245). The very act of thinking, according to these theorists, is to “put into words a possibility for becoming” (245). But what is at stake in this risk? By re-thinking subjectivity and its excesses, to Mason 9 what do we expose ourselves, and what do we risk becoming? I argue that we risk shame, a momentary disintegration of the self that is the very precondition for multiplying identificatory possibilities. Writing through a psychoanalytic lens, Britzman suggests that the collision between queer theory and pedagogy enables an encounter with otherness that challenges how we recognize ourselves (82). Since academic otherness is so integral to our sense of self, as I have argued, an actual exposure to this other-in-excess can reveal the ostensibly stable self to be a fiction. What we must begin to imagine, Britzman argues, is how to “account for the confusion that results when one’s own sense of cohesiveness becomes a site of misrecognition, or for the trauma provoked when the discourses borrowed to work upon and perform the fictions of subjectivity stop making sense” (85). In the context of this paper, what happens when we risk an encounter with someone we consider to be an academic other? What takes place when we directly confront our instinctive fear of those who, to borrow from Derrida, will “address … the same questions to Marxism, to psychoanalysis, to the sciences, to philosophy, and to the humanities” (149)? What unfolds when we find ourselves hailed by a set of questions that we do not recognize as our own? “Reading,” Britzman suggests, “might then be a theorization of reading as being always about risking the self, about confronting one’s own theory of reading, and about engaging one’s own alterity and desire. … No one is safe because the very construct of safety places at risk difference as uncertainty, as indeterminacy, as incompatibility” (94). What Britzman calls the “[refusal] to secure thought” is also a refusal to believe that subjectivity is permanently fixed (94). She further poses a very provocative question: Mason 10 Are there ways of thinking about proliferating one’s identificatory possibilities so that the interest becomes one of theorizing why reading is always about … confronting one’s own theory of reading, of signification, of difference, and of refusing to be ‘the same?’ What if ‘difference’ made a difference in how the self encountered the self and in how one encounters one (95)? To expand our breadth of possibilities for identification, I argue, identity must first be temporarily reduced – or shamed – to nothingness through this risky encounter with otherness. Sedgwick suggests that shame is performative, a “form of communication” that marks a lack of recognition from the other and works to “[define] the space wherein a sense of self will develop” (“Performativity” 5). Shame, “at once deconstituting and foundational” according to Sedgwick, “both derives from and aims toward sociability” (“Performativity” 5). The risk of shame is a performative one – the ability “to say ‘no’” in the words of Zournazi and Stengers (268), and to consider what Britzman has characterized as “the unthought of normalcy” (82). In the context of this paper, an academic project (and, as I have argued, a sense of academic self) can be disrupted by a fearsome set of questions perceived initially as strange or foreign. When this plays out, “the stage is set,” according to Sedgwick, “for either a newly dramatized flooding of the subject by the shame of refused return; or the successful pulsation of the mirroring regard through a narcissistic subject” (“Performativity” 6). In other words, the questions brought to bear on a given academic project can either confirm and normalize its existence, or, conversely, refuse identification with the project and gesture to its innumerable excesses. The latter, which I argue is a shaming of the project (and its Mason 11 author(s)), is a productive misrecognition that shakes the foundations of a stable academic identity by making the project feel queer to itself. This “deconstituting” shame (Sedgwick 5) is productive because, in challenging the completeness of an identity, it makes space for the “proliferation” of new possibilities for identification (Britzman 95). Who are these others with the power to destabilize subjectivities in such a profound manner? Furthermore, how does shame permit sociability, as Sedgwick has argued, and how can we begin to re-imagine social relations in the university when academic disciplines are put into question? In “The Social Triumph of the Sexual Will,” Foucault makes a call to re-think the “extremely few, extremely simplified, and extremely poor” relations available in our “legal, social, and institutional world” (158). I suggest that the university is one of such institutional spaces where we need to problematize the calcification of academic relations. Like Foucault suggests, we as academics “should try to imagine and create a new relational right that permits all possible types of relations to exist and not be prevented, blocked, or annulled by impoverished relational institutions” (“Triumph”158). If we risk exposure to unfamiliar discourses and sets of questions that prompt a shaming lack of reciprocal recognition, then we can create, from the “empty space” that once housed our seemingly fixed academic selves, what Foucault calls “new relational possibilities” (“Triumph” 160). When we theorize subjectivity as something that can be repeatedly questioned, deconstituted, rebuilt and multiplied, we enable a language that allows us to re-think the idea of a university as a community, as well as how the members of such a community relate to one another. Britzman poses the question: Mason 12 In claiming as desirable the proliferation of identifications and critiques necessary to imagine sociality differently … can pedagogy move beyond the production of rigid subject positions and ponder the fashioning of the self that occurs when attention is given to the performativity of the subject in queer relationality (81)? In other words, how do subjects who recognize themselves as less-than-complete or always-in-excess relate to other such subjects? In “Sociability and Cruising,” Leo Bersani unpacks the queer act of cruising – the eschewal of “normal” modes of relationality when engaging with the bodies of strangers – to elucidate his notion of the self-less subject. When gay men cruise one another, Bersani argues, they do so by setting their subjective baggage entirely aside; one body is willing to encounter another without concern for “who” that person may perceive himself to be. The pleasure derived from sociability, Bersani writes, “would not be merely that of a restful interlude in social life. Instead, it would be the consequence of our being less than what we really are” (11). This “willingness to be less” is what “introduces us … to the pleasure of rhythmed being”; we move metrically from one body to the next, interacting with others in such a way that ideological boundaries ostensibly dividing subjectivities are momentarily cast aside (Bersani 11). By not attempting to see ourselves reflected in or reaffirmed by the other, by not constructing the other in necessary opposition to ourselves, and by risking this lack of recognition to allow a momentary dissolution of our own sense of self, we can begin to re-imagine subjectivity; it is the sheer unknowability of the other with which we engage, a strangeness that points to the very alterity of our own self. This, it seems, is what Britzman is articulating when she poses the following question: “What if one Mason 13 thought about reading practices as problems of opening identifications, or working with the capacity to imagine oneself differently precisely in one’s encounters with another? … What if how one reads the world turned upon the interest in creating a queer space where old certainties made no sense?” (85). In the context of this paper, can we begin to see the university as a queer space where the arbitrary borders between disciplines and faculties are constantly put into question, and where the questions asked of one discipline can be asked of another? Can we think of the professor as someone who cruises – albeit in a strictly academic fashion – the discourses of others, regardless of their disciplinary attachments? Such queer reading practices could, as Britzman argues, “[unhinge] the normal from the self in order to prepare the self to encounter its own conditions of alterity: reading practices as an imaginary site for multiplying alternative forms of identifications and pleasures not so closely affixed to … what one imagines their identity imperatives to be” (85). The academic cruiser is but a queer version of Derrida’s “professor at large,” who does not “[belong] to any department, nor even to the university … [who] occasionally comes ashore, after an absence that has cut him off from everything. … He is given leave to consider matters loftily, from afar” (“Principle” 135). The professor at large seems to perfectly embody the rhythm of Bersani’s cruiser – coming and going, drifting in and out, choosing to engage with a department when he pleases, but always from a distance that initially avoids any specific subjective investment. Readings proposes something similar with a theorization of the “singularity,” which is his way of “talking about individuals other than as subjects” (115). He argues that singularities are radically heterogeneous, and never share “history, experience, whatever,” but rather “negotiate” Mason 14 without ever “[achieving] total self-consciousness” through their interactions (115). I believe Readings’ metaphor is a good one, although it does not describe how one can actually become a singularity. As I have argued, it is the initial risk of exposure to alterity – the willingness to confront a set of questions pointing to the excess of our selves – that disrupts the notion of transparent subjectivity. With this in mind, and recalling my earlier invocation of Edelman to argue that queer readings can only disturb identity, it seems productive to consider Readings’ call for “an abandonment of disciplinary grounding but an abandonment that retains as structurally essential the question of the disciplinary form that can be given to knowledges … the loosening of disciplinary structures has to be made the opportunity for the installing of disciplinarity as a permanent question” (177). Identity, subjectivity, and disciplinarity are dismantled, yes, but the traces of the shape they once took remain intact for the purposes of critical interrogation. As Britzman argues, queer pedagogy “[manages], however precariously, to be overconcerned with practices of identification and sociality and [used] as a technique for acknowledging difference as the only condition of possibility for community” (85-6). Is difference the appropriate word for this precondition, or rather a Bersanian sameness in selflessness? And can we come to think of the responsibility we have to consider identity and discipline in these more radical terms? These, perhaps, are some of the questions that must be asked repeatedly. Britzman’s positing of difference as the prerequisite for community, and her claim that pedagogy should “think about identity as a problem of making identifications in difference” (83) are complicated by Bersani’s suggestion that “it is the recognizing and longing for sameness that allows us to relate lovingly to difference” (17, my emphasis). Mason 15 An appreciation for sameness in selflessness, the kind seen in queer cruising, would seem to precede the proliferation of identificatory differences. But how can we come to understand this in a university context? In “The Principle of Reason,” Derrida elaborates the human subject’s preference for “sensing ‘through the eyes’” as a trope for understanding how the university purports to have a clear view – and thus exhaustive knowledge – of its “destination” (130). He addresses the limitations of vision, arguing that just as we must “shut our eyes to be better listeners” (131), so too must the university consider “[closing] its eyes or [narrowing] its outlook … to hear better and learn better” (132). To listen and not to look, as Derrida teaches us, is to put representation itself into question: to consider how images mediate our thinking and our understanding of difference. I am not attempting to privilege aural sensibilities over the visual, but rather argue that this notion of listening-without-seeing is an effective lever for, in the words of Readings, “[sketching] an account of the production and circulation of knowledges that imagines thinking without identity, that refigures the University as a locus of dissensus” (127). I emphasize here that Readings articulates thought as being initially devoid of identity entirely, not thought as being premised in a notion of identity based in inherent difference. When someone is heard and not seen, the visual cannot be privileged as the primary indicator of difference, and the listener is asked to (re)imagine her relationship to the speaking subject. Solely listening blinds us to the speaker; we cannot position ourselves in relation to her, nor can we position her in relation to ourselves. We cannot identify with her or identify in opposition to her; we must listen to what is spoken – from the ground zero of subjectification – before we can begin Readings’ process of negotiation between singularities. In more concrete terms, if I as an English scholar am Mason 16 having a set of questions brought to bear on my academic project by someone from another discipline, I must take the risk of listening to the questions – even if I fail entirely to identify with them – instead of seeing the difference of the person who speaks. If I see the other’s discipline, I could dismiss the questions by virtue of their very otherness, or rather see myself confirmed through my own identification with the speaker’s discipline or her questions. Negotiations between singularities must begin on a ruined, even ground: where I am summoned to recognize my project’s excesses – its always-alreadyincompleteness – and where both subjects “cruise” the other’s project from a space devoid of fixed subjectivity. Much like Bersani’s description of cruising, this is a moment of “identity-free contact – contact with an object I do not know and certainly do not love and which has, unknowingly, agreed to be momentarily the incarnated shock of otherness. In that moment, we relate to that which transcends all relations” (21). Following Readings, I argue that to listen in such a manner should be the responsibility of every academic. When the other speaks, Readings argues, we have a duty to listen – this is our responsibility to render reason, to answer to Thought. “To be hailed as an addressee is to be commanded to listen,” Readings writes, “and the ethical nature of this relation cannot be justified. We have to listen, without knowing why, before we know what it is that we are to listen to. To be spoken to is to be placed under an obligation” (162). As academics, we are-duty bound – in the name of Thought – to take the risk of listening and recognizing that the speaker may point to our own subjective incompleteness. In so doing, the speaker also problematizes the arbitrary structure of the faculties themselves. “To listen to Thought, to think beside each other and beside ourselves,” Readings Mason 17 continues, “is to explore an open network of obligations that keeps the question of meaning open as a locus of debate” (165). In other words, we have the responsibility to hear other discourses while speaking to the discourses of others; academically speaking, we must cruise and be cruised. It is perhaps under these terms – “the fact that we never know to whom our words may speak” (or who will speak to us) – that we can begin to address Readings’ question of “being-together” (156, 127). Structurally speaking, what could all this look like in the university? As Readings has suggested, disciplinary boundaries must be shaken for the purposes of interrogation, but not dissolved entirely. How can we make space for more academic cruising, for the constant and rhythmic disruption of calcified academic identities? It seems appropriate to take up Derrida’s notion of a “community of thinking … ‘at large’ – rather than a community of research, of science, or of philosophy” (148): a community of professors at large, seated in Derrida’s vacant chair, separate from the “normal” faculties, whose purpose is to irritate the projects of others by pointing to their incompletenesses and excesses. The professors at large would cruise, ghost-like, amongst the ruins of the university, haunting academic works by asking them to answer to Thought. This would take place in ruins that, according to Derrida, involve “multiple sites, a stratified terrain, postulations that are undergoing continual displacement, a sort of strategic rhythm” (150). Or is it possible for all professors to be somehow at large, in that they are dutybound to hear random, assigned projects at any given moment, or occasionally asked to speak their own work before a selfless listener? I wonder if cultural studies departments – paired, hopefully, with a queer theory counterscience – can be better utilized to fulfill this function. At McMaster, critical theory is taught to (and, reportedly, successfully Mason 18 irritates) health studies students; what other types of transdisciplinary work can we imagine? And how can professors from other faculties challenge us as cultural studies students? In a different context, Foucault argues that we must “work on [making] ourselves infinitely more susceptible to pleasure” (“Friendship” 137); indeed, we must take the risk of becoming vulnerable to other discourses, of feeling ashamed at the limits of our knowledge and subjectivity, and we must use this as a productive source of the pleasure that can come from dialogue, dissensus, and the multiplication of our possibilities for identification. Just as queer theory points to the rising positivism within cultural studies, we must be made constantly aware of our own un-thoughts and the potential for hope that arises from the queerness of the university. To conclude, I would like to briefly sketch a new trope for theorizing the university: the neighbourhood. In The Neighbour, Slavoj Žižek, Eric Santner, and Kenneth Reinhard discuss the theological roots and theoretical implications of the commandment to “love one’s neighbour as oneself” (1). For these theorists, the neighbour is someone who is proximally close yet infinitely distant: “An alien traumatic kernel forever persists in my neighbour; the neighbour remains an impenetrable, enigmatic presence that, far from serving my project of self-disciplining moderation and prudence, hystericizes me” (4). The bizarre commandment to love an infinitely foreign other as you love yourself is, according to Žižek, Santner, and Reinhard, “an enigma that calls us to rethink the very nature of subjectivity, responsibility, and community” (5). “Does the commandment call us to expand the range of our identifications,” they ask, “or does it urge us to come close, become answerable to, an alterity that remains radically inassimilable?” (7). Who, then, are our neighbours in academia – those who seem close Mason 19 but remain ultimately unknowable? We can imagine faculty members with adjoining offices but vastly different research interests: to one, the sheer alterity of the other’s academic discipline could feel threatening. Are they obligated to “love” one another, as the commandment stipulates? What about various departments and faculties who share buildings or even space on campus? What is their ethical obligation to one another? “Neighbour-love functions more as an obstacle to its own theorization than as a roadmap for ethical life,” argue Žižek, Santner, and Reinhard; “one cannot attempt to fulfill it without taking the risk of transgressing it” (5). Is there not something particularly queer about the commandment to love one’s neighbour as oneself in that it necessitates a transgression of ideological understandings of subjectivity? I would like to suggest that loving one’s academic neighbour as oneself means precisely what I have argued throughout this paper: that we have an ethical duty to bring our own set of questions to bear on those around us, even if those neighbours feel strange, foreign, and unknowable. The neighbourhood – or, perhaps even better, the Village – can be thought as a queer pedagogical space; like Bersanian cruising, it permits “an infinite series of possible encounters, one without limit and without totalization, a field without the stability of margins” (Žižek et al 8). “Hence,” as Kenneth Reinhard argues, “the neighbourhood opens in infinity, endlessly linking new elements in new subsets according to new decisions and fidelities” (67). We have an ethical imperative to move rhythmically, like Derrida’s professor-at-large, through the academic neighbourhood, professing neighbourlove for the strangers around us while asking what exactly it means to love our academic neighbours as such. Mason 20 At the end of “The Principle of Reason,” Derrida asks: “How is one to feel accountable for what one does not have, and is not yet? But what else is one to feel responsible for, if not for what does not belong to us?” (155). Derrida ultimately answers his own question with a resounding “I don’t know”; it is indeed difficult to imagine a duty to listen to others while subjecting ourselves to encounters with otherness (155). What I argue, however, is that this shift in thinking provides a powerful lens through which we can better imagine a means of navigating the ruins of Readings’ university. I suggest that queer theory, just as it points to the excesses of cultural studies, can also be used to transgress disciplinary boundaries and the divisions between the faculties while productively complicating our own subjectification as academics. Perhaps now, as Douglas Crimp contends, “we can begin to rethink identity politics as politics of relational identities formed through political identifications that constantly remake those identities” (qtd in Britzman 83). First, however, we must be willing to take the risks that enable a thinking past thought: a recognition that our own work, and the work of our academic neighbours, is really quite queer. Mason 21 WORKS CITED Bersani, Leo. “Sociability and Cruising.” Khalip 65-80. Britzman, Deborah P. “Queer Pedagogy and Its Strange Techniques.” Lost Subjects, Contested Objects. New York: State UP, 1998. 79-96. Derrida, Jacques. “The Principle of Reason: The University in the Eyes of Its Pupils.” Eyes of the University: Right to Philosophy 2. Trans. Jan Plug et al. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2004. 129-55. Edelman, Lee. No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Durham: Duke UP, 2004. Foucault, Michel. “The Human Sciences.” The Order of Things. New York: Pantheon Books, 1970. 344-387. ----------. “Friendship as a Way of Life.” Khalip 1-4. ----------. “The Social Triumph of the Sexual Will.” Khalip 5-8. Giroux, Henry A., and Susan Searls Giroux. Take Back Higher Education. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. Khalip, Jacques, ed. Queer in Theory: Identity, Intervention, Liberation. Hamilton: McMaster University, 2006. Rajan, Tilottama. “In the Wake of Cultural Studies: Globalization, Theory, and the University.” Diacritics. 13.3 (2001): 67-88. ----------. “The University As 'The Thought From Outside': Foucault and Derrida.” McMaster University, Hamilton. 7 Feb. 2006. Readings, Bill. The University in Ruins. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999. Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. “Gender Criticism.” Redrawing the Boundaries. Eds. Stephen Greenblatt and Giles Gunn. New York: The Modern Language Mason 22 Association of America, 1992. 271-302. ----------. “Queer Performativity: Henry James’s The Art of the Novel.” Khalip 133-148. Stengers, Isabelle and Mary Zournazi. “A ‘Cosmo-Politics’ – Risk, Hope, Change.” Hope: New Philosophies for Change. Ed. Mary Zournazi. New York: Routledge, 2002. 244-272. Žižek, Slavoj, Eric L. Santner, and Kenneth Reinhard. The Neighbour: Three Inquiries in Political Theology. Chicago: Chicago UP, 2005.