Module 4 – Case Study 3: Bipolar Disorder and Pregnancy

advertisement

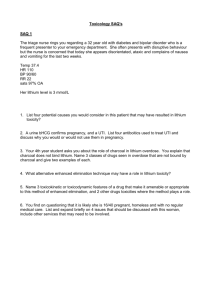

Module 4 – Case Study 3: Bipolar Disorder and Pregnancy Ngaire's Pharmaceutical Care Plan Ngaire is a 30-year-old married woman diagnosed with Bipolar Affective Disorder (BPAD) 4 years ago. She just found out that she is pregnant (6-7 weeks). Ngaire approaches you to discuss her medications as she is concerned how they can affect her child. History at presentation: Ngaire has had two acute episodes of mania since she was diagnosed with BPAD approximately 4 years ago. Two weeks ago she found out that she was pregnant (approximately 6-7 weeks). As soon as she found out she was pregnant she called her general practitioner (GP), who is currently managing her medications, to discuss this issue further. Her GP referred Ngaire to an obstetrician (her appointment is in three more weeks) and asked her to come to his office (she will be going there tomorrow evening). He also said he was going to talk to her psychiatrist at the local hospital. Ngaire has presented to discuss her medications. She is taking Lithium Carbonate 400mg BD, Citalopram 20mg daily and Alprazolam 0.5mg TDS. She explains that her GP told her to discontinue the Lithium but to continue taking the other medications. Possible diagnosis: Ngaire’s DSM-IV diagnosis using the multi-axial classification is summarised below: Axis I: Bipolar affective disorder Axis II: No reported personality disorders or mental retardation Axis III: Pregnant (6-7 weeks) Axis IV: Concerns about current medications affecting her child Axis V: Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score is unavailable but estimated to be approximately 80-90. Problem identification: The most pressing concerns for Ngaire’s management of her BPAD can be divided into the following: 1. Safety of her current medication regimen while pregnant 2. The risks to her offspring related to her psychiatric condition 1. Ngaire is in the first trimester of pregnancy and is hence particularly susceptible to medication effects on her unborn child. The risks with each medication is summarized below: a) Lithium: Many of the lithium studies in pregnancy predate 1995 and are primarily based on the Lithium Baby Register. Some initial reports indicated that the use of lithium during the first trimester of pregnancy was associated with an 11% incidence of birth defects, most of which were malformations of the heart (Ebstein’s anomaly). However, although newer studies indicate that lithium has little or no teratogenic potential, it is still classed as Category D for pregnancy. Some clinicians still recommend that especially during the period of cardiac organogenesis (2nd and 4th month of pregnancy) lithium should be avoided if possible. Neonatal toxicity (“floppy baby” syndrome) has been described with hypotonicity and cyanosis thus it has been recommended that “in women treated during the third trimester, the dose should be reduced by up to 50% just before delivery to minimize risk of toxicity in mother and fetus”. Lithium readily enters breast milk and can achieve potentially harmful concentrations for the infant. b) Citalopram: Overall, all SSRIs are considered to be safe for use in pregnancy. However, the use of SSRIs after the first 20 weeks of pregnancy may be associated with an increased risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Neonates exposed to citalopram late in the third trimester have developed complications requiring prolonged hospitalisation, respiratory support and tube feeding. Citalopram is classified as "C" meaning that studies in animals have revealed teratogenic/embryocidal or other effects but there are no controlled studies in women so use should be restricted to when potential benefits are greater than risks. It appears that there may be risks of withdrawal associated with citalopram use but teratogenicity is currently unclear. If used, consideration must be taken regarding benefits to be greater than risks. c) Alprazolam: Benzodiazepines are highly lipid soluble and can readily cross the placental barrier. Use of benzodiazepines during the first trimester of pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of congenital malformations, such as cleft lip, inguinal hernia, and cardiac anomalies. In addition, use of benzodiazepines near term can cause CNS depression in the neonate. Benzodiazepines easily enter breast milk and have the potential to accumulate to toxic levels for the infant. Alprazolam is classified as "D" (i.e. similar to lithium where there is a definite risk to the infant but dependent of risk vs. benefits in the patient). 2. A review of the literature indicate that overall there are no direct risks of negative effects on fetal development from untreated psychiatric disorders. However, the authors state that complications from a natural course of pregnancy (e.g. stress, depression, anxiety) have been linked with pregnancy complications. These patients are also more likely to engage in negative behaviours such as consuming alcohol or drugs. Similarly, antenatal stress and anxiety are linked with premature labour, low birth weight and other functional measures in neonates. Untreated maternal depression in the postpartum period has shown infants often have poorer developmental functions. Ngaire’s offspring may also be at an increased risk for mental illness later in life, as mental illness is considered to be inherited to some degree. However, this risk is increased as mothers with untreated depression are known to interact poorly with their infants and this may lead to negative effects on the cognition of their growing infants. This poses an increased risk of problems associated with attachment and post-partum depression. Depression during pregnancy has been linked to low birth weight and pre-term delivery. If Ngaire was left untreated for mania this would present perinatal risks to her child, as pregnant patients in manic states may engage in impulsive, high-risk behaviours that endanger her, as well as the foetus. Desired outcome: The goals of pharmacotherapy in Ngaire’s case is to maintain a level of treatment that will manage her symptoms and reduce the risks of relapse, while at the same time, minimising the risks of harm to her child, as well as to Ngaire herself. An algorithm for the management of Ngaire has been attached at the end of the care plan as a quick reference. Therapeutic alternatives: The pharmacotherapeutic options available to Ngaire can be broadly categorized to: 1. Discontinue the medication 2. Change medication or dosage 3. Continue the medication Discontinuing or interrupting the medications that she is currently on means that she is at increased risk of relapse (although during pregnancy, it is thought to be risk neutral since relapse rates are similar at 57% in pregnant vs. 58% in non pregnant women. Recurrences have been quoted at 50% within six months and rapid discontinuation appears to increase the risk further. In one study, discontinuing lithium rapidly (1-14 days) vs. gradually (15-30 days) showed that gradually tapering off lithium lead to reduced relapse risk. The rates however, in relapse have been quoted to be similar to non-pregnant bipolar disorder patients discontinuing treatment. Since the pregnancy is often not detected until the period of cardiac development is finished, there may be no additional benefit in discontinuing lithium. The risk of relapse in the post partum (41-64 weeks) have been shown to be higher than in non pregnant patients (70% vs. 24% respectively). It has been suggested that lithium administration weakens the risk of postpartum relapse by five-fold when given shortly before birth (week 36) or within 48 hours of delivery and continued into postpartum period. In Ngaire’s case, monitoring (e.g. echocardiography at 16-18 weeks) is recommended. In terms of prophylactic therapies available to decrease Ngaire’s offspring risk of malformations, anticonvulsants such as sodium valproate and carbemazepine have a higher risk of neural tube defects compared to lithium. Folic acid should still be taken to reduce the risks of neural tube defects. Adjunctive treatment may include other agents. During pregnancy it has been suggested that hypomanic patients can benefit from environmental manipulation (e.g. sleep hygiene, reducing stress) and as required benzodiazepines may avert of attenuate a manic episode. However, once the episode has progressed, other medications and or electroconvulsive therapy along with hospitalisation may be required. Atypical antipsychotics such as olanzapine (10-30mg at bedtime), quetiapine (150mg to 400mg twice daily) are potential alternatives and have been shown to have some benefits in bipolar disorder. These may be a potential adjunct or alternative if lithium fails and relapse occurs. Weight gain, insulin resistance, gestational diabetes and preeclampsia with the atypical antipsychotics are a worry. Antidepressants for hypomanic phase as monotherapy without concurrent mood stabilizers can potentially precipitate mania. Current recommendations are for antidepressants to be used as monotherapy in patients with bipolar II depression at low risk of mania. But otherwise, antidepressants are not recommended for bipolar I patients. In moderate or severe depression, SSRI (but not paroxetine) along with cognitive behavioural therapy is recommended and there must be monitoring for manic symptoms. Optimal Plan: As previously discussed, lithium is probably the lesser of the three evils. Effects of lithium for the mother have been determined to have increased clearance and returns to pre-pregnancy levels shortly after delivery and recommendations are to monitor lithium levels closely before and after pregnancy. More frequent dosing (3-4 times daily) has been recommended to allow patients to maintain therapeutic serum levels although effects on fetus are unclear. The following should be considered: Start of the pregnancy - serum lithium levels can be affected by vomiting and sodium intake During pregnancy - renal lithium excretion increases (which may require increased dose) During onset of labour - doses should be decreased to avoid toxicity associated with blood loss and vascular volume Dosage should be adjusted according to levels since renal function and volume of distributions associated with pregnancy will affect serum levels. It has been recommended to check lithium levels every one to two weeks initially (especially if nausea and vomiting is an issue due to risks in dehydration) and in the third trimester. Once levels and psychiatric symptoms are stable monitoring can be less frequent and performed monthly. The optimal plan in managing panic disorder in Ngaire’s case may be to discontinue alprazolam and use it short term when she begins to experience the warning signs of relapse. The unlabelled use of citalopram includes panic disorder (Lehne, 2004); therefore any anxiolytic effects associated with citalopram may be sufficient in managing her panic disorder, provided that this is combined with non-pharmacological therapy, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). Patient counselling: Prior to providing education to Ngaire it would be important to establish her level of knowledge. She presented with concerns around the risk of her medications having an effect on her child, which suggests that she has insight into her condition. If possible, it would be beneficial to include Ngaire’s partner in the education session, as they could oversee adherence with medications. In the post partum stage, breastfeeding is another consideration in regard to psychotropic medication use. As had been previously mentioned there is a high risk of relapse during this time. Lithium is excreted into breast milk and due to reduce renal clearance in neonates and dehydration risks caution must be taken during breastfeeding. Benefits and risks must be discussed with Ngaire and an informed decision made. Pregravid? Yes No Discuss planned conception. Go over risks associated with conceiving on her medication. Revise alternatives to her current medication, including psychotherapies, lessteratogenic psychotropics, and ECT. Yes Yes No Continue medication until closer to the decision of conceiving. Consider tapering off medication if prior illness was of a mild-moderate severity rating and if there were no multiple hospitalisations. If the patient conceives, continue off the medication until 2nd trimester or throughout pregnancy if the mood is stable. If relapse occurs before the patient conceives or in the 1st trimester, restart the medication trial, choosing the least-teratogenic option. Yes Talk about the risks for relapse off medications. Wanting to conceive? Already pregnant? Continue medication through attempts at conception if the prior cause was characterised by multiple hospitalisations or marked morbidity. No Talk about specific medications used and their risks for teratogenicity. Consider switching to a relatively safer alternative, if available, and if no history of treatment nonresponse to safer alternative. Assess the patient’s current mood and length of wellness, as well as the severity of prior illnesses. Discuss the increased potential for relapse with the abrupt discontinuation of a mood stabiliser. Consider continuing medication in 1st trimester if prior course was characterised by multiple hospital admissions, impaired judgment, and/or suicidal ideations. 2nd and 3rd trimesters? Yes Continue medications if she is taking them and if her mood is stable. Go over the risks for postpartum relapse. To minimise the risks for postpartum relapse, talk about the option to restart medications at end of the 3rd trimester if the mood is stable and patient is not on medications. Restart the medications if mood is unstable and the patient is not on medications. Discuss lactation and medication use.