Corpus Linguistics - Use of corpora in translation studies

advertisement

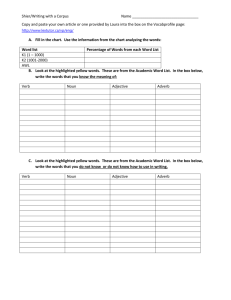

Words of desire in English and French 1. Introduction 1.1. Terms For this project the English terms desire, intend and wish were chosen as they have a certain degree of semantic overlap, but remain distinct enough in their scope to warrant further exploration as to their usage. Three corresponding French terms were also chosen as they can be considered as reasonable equivalents for the English terms; indeed avoir l’intention de, désirer and souhaiter could also be considered as having a large degree of shared semantic content with both the equivalent English terms and each other. 2. Methodology 2.1. Corpora and Engines 2.1.1. English For the English data, the BNC (2005) was chosen as it is a large corpus with over 100 million words, which allows reliable analysis of linguistic data as a large number of hits are attainable from a wide variety of sources. It is therefore possible to discover a wide range of senses for a given item, whilst ensuring a representative sample. The engine used to query the BNC was Kilgarriff and Rychly’s Word Sketch Engine (Kilgarriff and Rychly 2005 hereafter referred to as WSE), as this allows for a detailed analysis of concordances, giving information on collocates and other statistics. It is also possible to compare this with data obtained from the Leeds BNC engine (Sharoff 2005b) to see any discrepancies. 2.1.2. French For the French data, a corpus of data taken from Internet pages (Sharoff 2005c) was used, accessed via Sharoff’s interface (2005a), as this allows for a fuller analysis of concordance lines than other interfaces examined such as the Corpus Lexicaux Québécois (Gouvernement du Québec) or the Corpus Concordance French (Cobb), as it is possible to obtain statistics on collocations for a given item. A potential problem with this corpus is that the range of sources is not as wide as the BNC, but given the lack of a more suitable source of information it is necessary to work with what is available. 2.2. Method of Analysis For the English data, a concordance is created using WSE (Kilgarriff and Rychly 2005), searching for the relevant lemma. One problem that immediately appears is the tendency for a word to appear 00000000 MODL5007 Corpus Linguistics 1 repeatedly in one text, which could potentially influence the interpretation of a concordance due to the style of a particular author or a specific usage in a given domain. WSE gives the possibility of avoiding this by taking a random sample of a specified size from the concordance lines. This is not possible for the French data, as WSE only works with data from the BNC and Susanne (Sampson 2005). The internet corpus interface (Sharoff 2005a) does not offer this function, but however as it uses a smaller corpus there are fewer hits for each word, which gives a workable number of concordance lines from a wide range of sources. For both languages it had been hoped to work with a sample of 150 concordance lines which should be wide enough to gain a reasonable sample to work with, although unfortunately for the French data this is sometimes below the 150 hits stipulated, but in all cases the number received is close to this number. In order to examine the collocates for the verbs, it is necessary again to employ a different strategy for each language. WSE offers the possibility of producing a word sketch for English lemmas, which gives subjects, objects and other types of segment that frequently appear with a given lemma. For French this is sadly not possible, but the internet corpus does offer the possibility of computing the collocation statistics for a query. It is possible to calculate the LL, MI and T scores for collocates; in all cases, the most useful statistical measures for dictionary writing using this method tend to be the LL and T scores, which produce very similar results. With both of these, the collocates with the highest scores are the strongest collocations and are those used in this project. It is however useful to read the lists to note any other collocations that were important to include. It is also possible to search for collocates according to their part of speech. For verbs, it is particularly useful to search for nouns on the left or right in order to discover any collocation patterns for subjects and objects. It is also useful to search for adverbs on the left or right in order to determine the sorts of adverbs used with these verbs. Avoir l’intention de presents a particular case, as this construction is always followed by a verb, so it is therefore not useful to look at the right context. There are, however, two possible places an adverb could be placed: to the left of the verb group or to the right of avoir. It is therefore necessary to do a search for collocates of avoir le intention de and also le intention de. Adverbs and adverbial phrases are classed according to Melčuk’s lexical functions (Wanner, p.22); the most common lexical functions found with these are magn (intense) and ver (genuine). 3. Analysis 3.1. Desire When searching for concordances for desire, it is important to ensure that there are no concordances found for the noun desire, which gives false results. In order to avoid this, in WSE it is possible to select the part of speech for a given lemma, thus ensuring that only verb forms are found. This problem is only present in the words chosen here in desire and wish, but had the same problem been the case for 00000000 MODL5007 Corpus Linguistics 2 any of the French verbs, it is possible to limit the hits from the noun forms using CQP syntax. In this case, a search in the form [lemma=“x”&pos=“V.*”], where x is the verb required filters the results, only allowing the corpus query processor to display verb forms (assuming the corpus has been correctly tagged). Upon examination of the concordance of desire, there is one specific pattern that is immediately obvious upon sorting the lines according to the right context. By far the most common pattern is desire followed by a verb in the infinitive. When we examine noun phrases that appear in object position (to the right of the verb) it becomes clear that there are two types: abstract and concrete. The sorts of abstract noun that appear most frequently with desire are nouns like cooperation and peace. Indeed, when a word sketch is performed in WSE, we find peace listed as the most common object of this verb. Another pattern that becomes clear upon examination of the concordance lines is the construction to leave a lot/a great deal/much to be desired. This had a corresponding French expression that will be discussed below. When we compare the modifiers that appear with this verb in the BNC in WSE with those we can discover the Leeds BNC engine (Sharoff 2005b), we see that there are fewer results in WSE. In these examples we see that the sorts of adverbs associated with ‘desire’ according to WSE are so, much and really. The Leeds engine allows us to search for adverbs to the left and right of the lemma we are searching for. In this way, it was possible to find adverbs and adverbial phrases such as a great deal and earnestly. 3.2. Intend One thing that is immediately clear upon querying the BNC using either engine is the level of formality compared with desire. There is a sense of intend which seems to be found in legal and political discourse that we do not find with desire that evokes a decision. When we examine the collocates for this verb, we can see that the adverbs and adverbial phrases tell us something about the nature of the verb. Originally and primarily are among the collocates, which shows us something about the semantic content of intend. We see that intend is used to talk about an individual’s or a group’s plans with reference to the extent to which the plan was carried out; using originally with intend shows that the outcome differs somehow to the plan, whereas primarily infers that there are secondary effects. Other common collocates are fully and clearly, which again give information about the extent and scope of a plan. This continues into the constructions used with this verb, we see that no pun intended shows a divergence from a plan with an unintentional slip-of-the- 00000000 MODL5007 Corpus Linguistics 3 tongue. In a similar vein, WSE gives joke as one of the collocates, showing that intend is used when talking about offence. There seems to be a degree of negative semantic prosody here, though not as strong as that described by Hunston (2002, p.119), in that this verb conveys the idea of the failure of a plan, usually to someone’s detriment. The subject collocates for this verb also evoke a legal and political domain. WSE gives parliament and defendant as two of the main collocates, which are clearly linked to this type of discourse. 3.3. Wish As with desire, it is necessary to specify that the lemma being searched for was a verb to avoid any confusion with the noun forms of this word. This works in most cases, assuming the texts being queried have been correctly tagged. It is possible to discern several senses of the verb wish by looking at the concordance lines from the BNC. Wish is generally used to refer to a desire that is unattainable for some reason given the current situation. This may be because the event that precludes the desired outcome has already passed or that it is simply an impossibility (particularly in the usage to express a wish – I wish to be rich). This meaning is shown particularly well in the usage that is used to express regret (I wish I could do that) One meaning that clearly distinguishes wish from the other usages we have examined where it replaces want in formal styles. This is a more concrete usage than the others we have examined as it does not refer to an abstract plan or desire, rather a more immediate want. Upon examining the collocates for wish, we find very specific uses that involve large events such as to wish someone a happy birthday/merry Christmas, or more general usages that involve hoping someone will be lucky or healthy. 3.4. Avoir l’intention de As previously explained, this construction poses a problem as it is the only example of a phrase that needed to be queried. It is necessary to create a query that searched for each element using its own lemma. Due to the gender system in French it is interesting to note that although intention is feminine, the article la is lemmatised in its masculine form le. Searching for avoir le intention de enables us to find all forms of this verb and discern patterns. As with its English equivalent to intend this item has a strong feeling of a difference between a planned event or situation and the outcome. This is shown in the specific meaning that is translated by to mean to do sth or to not intend to do sth. 00000000 MODL5007 Corpus Linguistics 4 Another meaning that clearly has a direct English equivalent is the academic sense to set out that is used to describe the intentions of a writer in a journal, paper or essay. 3.5. Désirer Désirer is perhaps the item that has the closest mapping between English and French, with very similar senses to the English desire. It may be noted however that désirer may be considered somewhat less formal than the English, as we see that it is possible to translate it by using a more generic verb such as want. It is not particularly surprising to find a high degree of semantic overlap between these items; like a high proportion of English and French words, the two forms described here both have a shared Latinate base dēsīderāre. In the sample of concordance lines it is perhaps due to the more restrictive nature of the internet corpus that there are fewer meanings that can be ascertained. 3.6. Souhaiter As well as the meanings discussed for wish above, it is clear that souhaiter has some supplementary related meanings: English uses a different verb for souhaiter la bienvenue and souhaiter bon soir. We are much more likely to bid someone good evening, for example when parting, and to use a different verb when greeting. It is however possible to use souhaiter in both cases in French. Another specific meaning in the French is souhaiter la bienvenue that requires the use of a different verb in English; this meaning is conveyed by to welcome in English. It is interesting to note that French also has a specific verb for this, accueillir, but it seems that both verbs can be used. It is also interesting to note that the French does not give the possibility of conveying the same sense of wish that refers to someone’s heart’s desire. Souhaiter used in this way carries only the weaker meaning. 4. Conclusion In this limited study of only a few items it is clear that the meanings discovered are very similar across the two languages. However, it has been possible to discover different usage restrictions through the examination of collocates and other phenomena through the exploration of corpora using different interfaces that may prove useful to translators and lexicographers. 2179 Words 5. References 00000000 MODL5007 Corpus Linguistics 5 British National Corpus (2005) British National Corpus [Internet] Oxford, Oxford University Computing Services. Available from <http://www.natcorp.ox.ac.uk> [Accessed 11/12/05] Cobb, T (2005) Corpus Concordance French [Internet]. Montréal, Université du Québec à Montréal Available from <http://www.lextutor.ca/concordancers/concord_f.html> [Accessed 14/12/05] Gouvernement du Québec (2005) Secrétariat à la politique linguistique – Corpus Lexicaux Québécois [Internet] Québec, Gouvernement du Québec. Available from <http://www.spl.gouv.qc.ca/corpus/index.html> [Accessed 14/12/05] Hunston, S. (2002) Corpora in Applied Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Kilgarriff A. and Rychly, P. (2005) Word WSE [Internet]. Lexical Computing Ltd. Available from <http://www.sketchengine.co.uk> [Accessed 11/12/05]. Sampson, G. (2005) Geoffrey Sampson: Susanne Scheme [Internet]. Available from <http://www.grsampson.net/RSue.html> [Accessed 11/12/05] Sharoff, S. (2005a) A Query to Internet Corpora [Internet]. Leeds, Leeds University Information Systems Services. Available from <http://corpus.leeds.ac.uk/internet.html> [Accessed 1/12/05]. Sharoff, S. (2005b) A Query to English Corpora [Internet]. Leeds, Leeds University Information Systems Services. Available from <http://corpus.leeds.ac.uk/protected/> [Accessed 1/12/05]. Sharoff, S. (2005c) Creating general-purpose corpora using automated search engine queries. In Baroni, M. and Bernardini, S. Web as corpus. Wanner, L. ed. (1996) Lexical Functions in Lexicography and Natural Language Processing. Philadelphia/Amsterdam, John Benjamins Publishing Company. 00000000 MODL5007 Corpus Linguistics 6