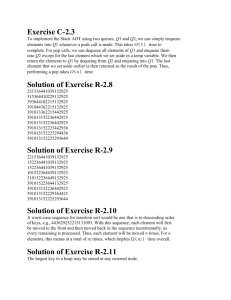

Grounding Dynamic Capability 2011

advertisement