`Living` Sati - The University of Sydney

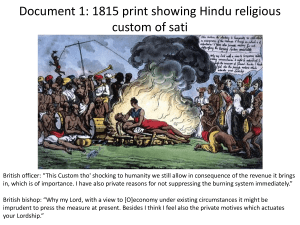

advertisement

The ‘Dying’ and the ‘Living’ Sati: Chastity and Widowhood in India Jyoti Atwal In terms of numbers, the widows in India comprise 34 million souls and the overall share of widows to total population of women in India is 6.9%.1 In general, widows form a significant proportion of all adult women in the world. The world over it varies from 7 to 16 percent. Indian scenario is interesting as the widows form about 1 percent of all younger women between the age of 15 and 35. Widows account for 12 percent of all middle aged women between the age of 35 to 59; and 55 percent of women above sixty years of age. Nearly thirty thousand widows are below the age of fifteen. On the other hand, the widowers in India are less than three percent of the adult male population. In the rural areas factors such as illiteracy, caste loyalties and ideas of honour, preference for male child, arbitrariness of property claims and maintenance rights of the women as daughters, wives and widows, place women in a relatively more vulnerable situation than their urban counterpart. The entire context of widowhood in the rural areas is dominated by the notion that a widow is inauspicious and this is used to justify her exclusion from society and to deny her access to resources, cultural as well as economic. My paper will look into the historical continuity of two dominant ideas on widowhood and chastity since the colonial period in India: the idea of the dying sati (ancient Hindu custom of widow immolation) and the idea of the ‘living’ sati. The production of colonial knowledge about the Hindu widow in early 19th century through the category of sati led to an enquiry into the Hindu religious – socio – cultural realm. The extent to which the issue of Hindu self immolating widow or the ‘performing’ sati caught the colonial attention is testified by the fact that by the year 1830, House of Commons had ordered printing of six volumes of Parliamentary Papers on burning of the Hindu widows. Apart from the weak 19th century social reform, a variety of nationalisms emerged by the early decades of the 20th century that had 1 Census of India, 2001,Marital Status by Religion, Community and Sex, Table C3.. crucial implications for the public debate on widowhood. All forms of nationalism like Gandhian one, were faced with the crisis of loss of the material domain. They were left with only the spiritual one. Gandhi seems to have borrowed his discourse on inner domain from the widow’s spiritual domain. He introduced the ideas of celibacy and renunciation into the active sphere of politics. Gandhi’s articulation of sexual self discipline and the inner feminine strength of a widow to preserve her chastity and honour had a precedent in Hindu widow’s own perception of her honour. The enduring popularity of the idea of Mother India was shaped by the Indian experience of suffering and belief in God’s will, remaining stoic and steadfast in the face of misfortune. These were the elements which constructed the image of the heroic mother. It is noticeable that the film is much about a widow’s struggle but not with ‘widowhood’ alone. This struggle responded to a complex matrix of economic pressures of a ‘feudal/landlord’ rural peasant society where colonial ‘modernity’ was not a feasible alternative or option. Dr Jyoti Atwal teaches gender history at the Centre for Historical Studies, School of Social Sciences Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. She is at present a guest scholar at University of Sydney and is collaborating on a joint project with Dr. Tim Allender on ‘Education and Dalits in Colonial Punjab’. Her area of specialization is Indian women in the reformist, nationalist and contemporary perspectives; dalit women’s history; entangled histories of Indian/English/and Irish women. She has also published in the field of comparative cultural studies on Korean, Afghani, African and Swiss women. Her latest publication includes ‘Foul unhallow’d fires’: Officiating Sati and the Colonial Hindu Widow in the United Provinces’, in Studies in History, 29.2 (2013): 229-272.