The development of personal identity in young people

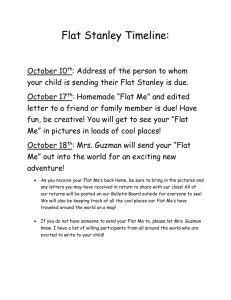

advertisement