Cover Page - The Earth Institute

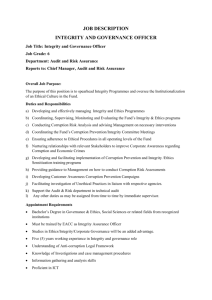

advertisement