Outline

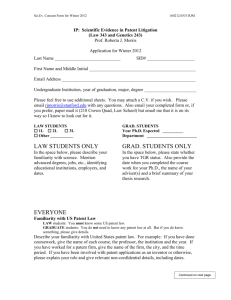

advertisement

Patent Models INTRO – compare to NEMES show in Feb, discussion with Dick re Patent Models Who am I I. What is a patent model A. Patents – contract, written description, figures… B. Models – only in USA 1790-1880, working scale model C. Cottage industry in Washington II. History A. Patent Law of 1790 – Jefferson B. Burning of Washington Aug 25, 1814 (War of 1812) C. Great fire of December 13, 1836 a. 10,000 patents and models lost b. 2800 restored – x series c. rest canceled D. September 24, 1877 fire a. No patents lost b. 75,000 models lost E. Law change in 1880 – patent applications increase significantly F. Moved to storage in 1893 – 150,000 to abandoned stable G. Disposal in 1925 a. Smithsonian b. Inventors and family c. Libraries, etc d. Sale of patent models H. Sir Henry Welcome purchase, planned museum I. Alan Rothchild purchase – 1990s III. Sample Models CONCLUSION: Great job for model builders Patent Model Background From Rothschild Patent Museum www.patentmodel.org Originally enforced by a commission including Thomas Jefferson, the Patent Act of 1790 required that anyone applying to the U.S. Patent Office submit a working model of the invention. Over 200,000 models were submitted during the next 90 years, but after two fires and a growing lack of space, the model requirement was abolished in 1880. Congress sent some models to the Smithsonian Institution, but the bulk was sold at auction in 1925. The winning bidder was Sir Henry Wellcome, founder of what is now the Glaxo-Wellcome pharmaceutical company. After Wellcome's death, the collection was broken up and thousands of models were sold off by a succession of private owners. Alan Rothschild acquired the remainder of the original collection in the 1990s from Cliff Petersen, and established the Rothschild Petersen Patent Model Museum in 1998. Since then, Mr. Rothschild has added to the Museum with purchases of smaller patent model collections from around the United States, including the purchase of all 82 models in Carolyn Pollan's Patent Model Museum in Fort Smith, Arkansas. The Rothschild Petersen Patent Model Museum contains nearly 4,000 patent models and related documents. Due to limited space, only a fraction of the models are on display. Alan Rothschild hopes to establish a national Patent Model Museum. See the "Vision for the Future" section for more details. WIKI A patent model was a scratch-built miniature model no larger than 12" by 12" by 12" (approximately 30 cm by 30 cm by 30 cm) that showed how an invention works. It was one of the most interesting early features of the United States patent system. Since most early inventors were ordinary people without technological or legal training, it was difficult for them to submit formal patent applications which require the novel features of an invention to be described using words and a number of diagrams. Actually, the patent system then was very crude by today's standards. It was a good idea for these amateur inventors to submit a model with a brief explanation or drawing of it. Patent models were required from 1790 to 1880. The United States Congress abolished the legal requirement for them in 1870, but the U.S. Patent Office (USPTO) kept the requirement until 1880. Some inventors still willingly submitted models at the turn of the twentieth century. [edit] Working model Patent models were required up until 1880 but are no longer required by the USPTO. However, in some cases, an inventor may still want to present a "working model" as an evidence to prove actual reduction to practice in an interference proceeding. The models were sold off by the patent office in 1925 and were purchased by Sir Henry Wellcome, the founder of the Burroughs-Wellcome Co. (now part of GlaxoSmithKline). Although he intended to establish a patent model museum, the stock market crash of 1929 damaged his fortune; the models were left in storage. After his death, the collection went through a number of ownership changes; a large portion of the collection--along with $1,000,000--was donated to the nonprofit United States Patent Model Foundation by Cliff Peterson. Rather than being put into a museum, these models were slowly sold off by the foundation. A saga of legal wrangling, purchasing, and re-selling ensued.[1] A comparatively small number of models (4,000) are currently the property of the Rothschild Patent Museum.[2] February 18, 2002 Patent Models' Strange Odyssey By TERESA RIORDAN N the 1870's, the United States Patent and Trademark Office was a big tourist attraction in Washington. Its Parthenon-inspired facade, along with the United States Capitol, dominated the skyline. Inside, visitors roamed its grand galleries, peering into glass cases that stretched from the floor midway to the 20-foot vaulted ceilings. The cases held patent models — Lilliputian reproductions of inventions that ranged from Morse's telegraph to waltzing dolls and collapsible hoop skirts. Last week, after a strange and perilous odyssey that lasted nearly a century, some of those models went back on display — at the patent office's museum in Crystal City, Va. Most of the 50 models in the new exhibition are on loan from Alan Rothschild, a former pharmacist who is now a health care executive in Syracuse. "Patent models represent a way we can visually turn back time 100- plus years," Mr. Rothschild said. The museum, which is tucked into a glass-and-steel office tower, lacks a 19th-century ambience. But the patent models evoke their era: an "apparatus for breaking and subduing horses," a reed organ, an "earth scraper" (others might call it a plow), an "atmospheric and vacuum egg beater," a coffin with a window and so on. The patent office required that inventors submit models with their applications until 1880, when it deemed that models were no longer necessary except for perpetual motion contraptions and flying machines. After the Wright brothers demonstrated flight, the agency dropped the model requirement for flying machines; the exhibition features a 1902 model for a "blade for propellers for airships." (Anyone submitting a perpetual motion patent application would still be required to provide a proof-of-concept model.) Although some models were crudely built by their inventors, many were made in Washington by about a dozen model-making shops for whom patent work had become a cottage industry. Some models can be perceived as not only artifacts from the history of technology but also as finely wrought examples of folk art. Mr. Rothschild, who owns about 4,000 patent models and exhibits some of them in a small museum in his house, hopes to establish a permanent museum dedicated exclusively to patent models. He is by no means the first person to have this ambition, but the nation's patent models have not exactly lived a charmed life. "Many people have had dreams of doing something big with these, but none of these dreams has ever come true," said Robert C. Post, who is a former curator at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History and currently a senior fellow at the Dibner Institute, a science and technology historical research center in Cambridge, Mass. In 1836 a fire destroyed the patent office and its records, including models. In 1877 a second fire destroyed 76,000 models there. By 1893 the agency was strapped for space, so it hauled about 150,000 models to an abandoned livery stable. Congress ordered them sold in 1925. Before that sale, though, curators from the Smithsonian were allowed to cull the models to take what they wanted. Some models were returned to the inventors' families, and many were destroyed. The remaining lot was sold to Sir Henry Wellcome, the founder of the Glaxo Wellcome pharmaceutical company (now called GlaxoSmithKline (news/quote)), who intended to establish a patent model museum. But he abandoned those plans after the 1929 stock market crash. Over the next decades the models were acquired by a Broadway producer, then by a group of businessmen who went bust and finally by an auctioneer. In 1979, Cliff Petersen, an aerospace engineer, bought 800 crates of models — about 35,000 models — many of which were in their original government packing. Mr. Petersen donated 30,000 models and $1 million to the United States Patent Model Foundation, a nonprofit organization whose goal was to set up a museum. That effort, however, went sour, and later was the subject of an unfavorable report by the investigative TV program "20/20." When Mr. Petersen died last year, Mr. Rothschild acquired several thousand patent models from Mr. Petersen's estate. The remaining models are scattered in public and private collections throughout the United States. The Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village in Michigan, the Hagley Museum and Library in Delaware and the Smithsonian all have significant collections. A number of individuals have also amassed collections. Diane Davie of Woodbridge, Va., is such a collector. She and her husband, Jim Davie, who is a patent examiner and recognized as the agency's unofficial historian, own about 200 models. Several patent models are sold every month on eBay (news/quote). This month a washing machine went for about $3,000. Mrs. Davie said that the best way to establish a model's provenance was to have its original patent office tag attached, often with a red ribbon, an arrangment that supposedly gave rise to the expression "government red tape." "Otherwise," Mrs. Davie said, "it's hard to know that it's not just a salesman sample." The largest share of patent models appears to be held by J. Morgan Greene, who was affiliated with the United States Patent Model Foundation. Mr. Greene could not be reached for comment, but several patent model aficionados attested that as recently as a year ago they saw the collection — of about 20,000 models — stored in a warehouse in Alexandria, Va. Mr. Post applauded Mr. Rothschild's efforts, noting that historians could learn from such artifacts. But he said that because the models required considerable space and maintenance, a museum would need a fat endowment. "You would have to establish the right pitch about how these symbolize ingenuity and what we revere about our national character," Mr. Post said. "And then you would have to go to someone like Bill Gates and ask for $50 million." PRESS RELEASE Contact: Kim Byars 703-305-8341 kim.byars@uspto.gov February 11, 2002 #02-11 Patent Models: Icons of Innovation USPTO Museum Opens New Exhibit Showcasing American Ingenuity The Department of Commerce's United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) today unveiled its newest periodic exhibit "Patent Models: Icons of Innovation," in celebration of the 155th anniversary of Thomas Edison's birthday. In the 19th Century, the United States was the only industrializing nation that required patent applicants to submit a model along with a description and detailed drawing of their invention, resulting in thousands of crafted miniature machines. Those that survive today compose a national treasure chest that captures a very specific chapter of American history - a treasure chest the USPTO is committed to preserving. The USPTO exhibit showcases some of the more interesting patent models from this era. Patent models were first housed in Blodgett's Hotel in downtown Washington after the Patent Office moved there in 1810. Two fires and the general chaos of the Civil War threatened their future before their enormous quantity made them an unwanted nuisance in the 1880s. In the next century, the miniature machines changed hands many times, surviving more fires, auctions and general neglect. The Smithsonian Institution received some historically significant models in 1907 and 1924, but many boxes were never opened. Today, thousands of patent models have ended up in the hands of New York businessman Alan Rothschild. The model collector and inventor in 1998 opened the Rothschild Petersen Patent Model Museum, the largest accessible private collection of patent models in the country. Among the 50 models on display are some of the most significant in the Rothschild collection, plus Thomas Edison's light bulb, (# 223,898). Although Edison did not invent the light bulb, he dramatically improved it by developing carbonized filaments that would glow for hours inside their oxygen-emptied glass globes. Nelson Goodyear's India Rubber (# 8075) is also displayed. Other models of significant inventions on display include the Washing Machine (#90416), the Steam Generator (#80543), the Telegraph (#76748), the Universal Joint (#197541), the Refrigerator (#88468), the Sewing Machine (#16434), and the Plow (#369727). A patent signed by President Thomas Jefferson and Secretary of State James Madison will also be displayed. Established in 1995, the Patent and Trademark Museum strives to educate the public about the patent and trademark systems and the important role intellectual property protection plays in our nation's social and economic health. The museum features a permanent exhibit that explains what intellectual property is and how it is protected. It is now run by the National Inventor's Hall of Fame. "Patent Models: Icons of Innovation" runs through May 2002 and can be seen at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office Museum, 2121 Crystal Drive, Suite 0100, Arlington VA.