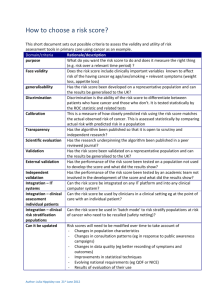

Guidance: Validation Consultation draft

advertisement