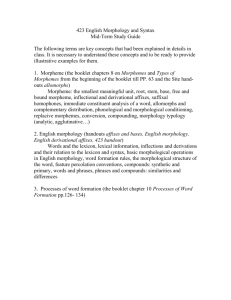

2. Identifying a Word. Morphological Structure of the Word 2.1

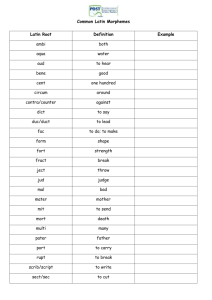

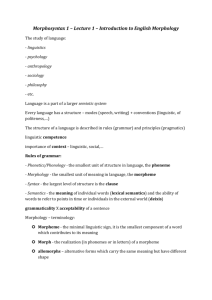

advertisement

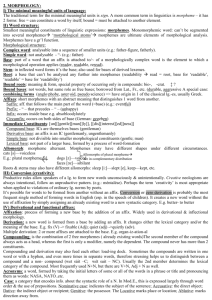

2. Identifying a Word. Morphological Structure of the Word 2.1. Problems of the Definition of the Word 2.2. Lexical and Grammatical Words 2.3. Morphological Structure of the Word 2.4. Types of Morphemic Segmentability 2.1. The Problems of the Definition of the Word Defining a word is considered to be one of the most complicated tasks in linguistics because the simplest word has many different aspects: 1) phonological, as it has a sound form; 2) morphological, as it is a certain arrangement of morphemes; 3) syntactic, as it may occur in different word forms and signal different meanings. The word being the core element of any language system has been in the centre of attention of many scientists who have attempted to define the word. One of the best-known definitions of a word was proposed by the American linguist L. Bloomfield, who defined it as a minimum free form. The French linguist A. Meillet combined three approaches and defined a word as follows: a word is defined by the association of a given meaning with a given group of sounds susceptible of a given grammatical employment. The discussion may still arise when we try to define a word on the following levels: · Orthographically words may be spelt differently: teapot, tea-pot, tea pot. Words are written separately, but not all words fit this category, e.g. will not – two words; cannot – one word. · There may be found different forms but different forms are not necessarily regarded as different words, e.g. teach, teaches, taught, teaching; nice, nicer, nicest – are not separate words, as we do not expect to find each form separately in a dictionary. · Some words can have the same forms but completely different and unrelated meanings, e.g. fair. · The existence of idioms and phrasal verbs seems to upset attempts to define words in any formal way, e.g. to kick the bucket – “to die”, to put off – “to postpone”. Thus, by a word we mean a lexical item or lexeme, i.e. the technical term for “dictionary entry”. A lexeme is the abstract unit which underlies some of the variants we have observed in connection with “words”. Thus, teach is the lexeme which underlies some of the variants teach, teaches, taught, teaching which are the word-forms. Lexemes are basic units of vocabulary in a language. The term lexeme is also connected with more than one word-form expressed by such lexical items as: Multi-word verbs, e.g. to keep up with; Phrasal verbs, e.g. to give up, to switch on; Idioms, e.g. kick the bucket. 2.2. Lexical and Grammatical Words Linguists distinguish between lexical words and grammatical words. Lexical words known as full words or content words include nouns, adjectives, verbs, adverbs and belong to the open classes of words. They carry a higher information content and are syntactically structured by the grammatical words. Let’s consider each of them. Nouns A noun can be defined as a naming word. It gives the name to a person, place, thing, etc. Most nouns possess the category of number and have a plural form: -s or -es, e.g. boy – boys, watch – watches, video – videos, photo – photos. Some words make their plural forms in a different way, e.g. foot – feet, goose – geese, mouse – mice, child – children, man – men. Other nouns never change their singular forms to make their plurals, e.g. deer – deer, fish – fish, sheep – sheep. Some nouns never occur without the plural marker, e.g. scissors, trousers, jeans, spectacles. Most nouns are used with either the indefinite article a, or the definite article the. Some nouns can be countable, some – uncountable. All nouns fall into three groups: those which appear in all four groups, those which appear in only one group, those which appear in some groups. The nouns which appear in all four groups are called countable; those which appear in only one are called uncountable. Adjectives Adjectives denote a property or quality of an object. All adjectives fall into two groups: gradable and non-gradable. Gradable adjectives take grammatical forms and represent degrees of comparison: positive, comparative, superlative, e.g. short – shorter – the shortest; beautiful – more beautiful – the most beautiful. Adjectives in English may appear either before a noun or after a verb, e.g. juicy apple, get wet, be happy. Not all adjectives appear in both positions. Some may only appear before nouns, while others appear only after the verb. Verbs There are two classes of verbs – lexical and auxiliary verbs. Lexical verbs denote actions or states. Each verb has five associated grammatical words, e.g. define – defines – defined – defining – defined; do – does – did – doing – done. Verbs like define are regular; they form the majority of verbs in the English language. Irregular verbs like go have different forms; they are about 200 in number. Adverbs Two classes of adverbs can be singled out: degree and general. Degree adverbs are a small group of words like quite, far, very, more, and most. They always appear with either an adjective or a general adverb, e.g. She drives very well. His story is quite interesting. This landscape is more beautiful. General adverbs form a large class and may appear without a degree adverb, e.g. He cooks well. Adverbs denote degree, manner, place, time. Adverbs have no inflected forms, they take comparisons like adjectives. Grammatical words comprise a small class of words that includes pronouns, auxiliary verbs, determiners, prepositions, conjunctions. They are also known as functional words, or empty words. Here they are. Pronouns are words that take the place of nouns, noun phrases. They can be of different types: personal (I, we, she), demonstrative (this, those), possessive (mine, yours), interrogative (whom, whose, which), etc. Auxiliary verbs such as have, do, did, will determine the mood, tense, or aspect of another verb in a verb phrase. They always precede main verbs within a verb phrase. Determiners introduce nouns; they are articles (a, an, the), quantifiers (some, much). Prepositions are words that show the relationship between a noun or pronoun and other words in a sentence. They indicate locations in time or space (at, in), agency (by), comparison (like, as . . . as), direction (to, toward, through), place (at, by, on), possession (of), purpose (for), source (from, out of), and time (at, before, on), etc. Conjunctions serve to connect words, phrases, clauses, or sentences, e.g. and, but, for, or, nor, yet, so. Grammatical words belong to the closed classes of words, i.e. they do not accept new members. 2.3. Morphological Structure of the Word Words consist of morphemes. This term was derived from Greek: morphe– “form” and -eme – “smallest unit”. Nowadays in linguistics a morpheme is defined as the smallest meaningful unit of speech, which cannot be split up into smaller segments. Unlike a word a morpheme is not autonomous. They occur in speech as constituent parts of words, not independently. A word may consist of a single morpheme or contain several, e.g. shelf (one morpheme), indisputable (3 morphemes) – in-disput-able. Linguists identify morphemes by comparing a wide variety of utterances and finding similarities. The morpheme in can be found in words insignificant, inexpensive; the morpheme able – in words excusable, reliable; the morpheme dispute – in such words as disputing, disputes. Some morphemes have only one phonological form, while others may have a number of variants which are known as allomorph. Let’s study the example: pronounce these words please, pleasing, pleasure, pleasant. The root morpheme is represented by different phonological forms. These representations of the given morpheme are called allomorphs or morphemic variants. Thus, an allomorph is defined as a positional variant of a morpheme occurring in a specific environment and characterized by complementary distribution. Allomorphs may vary substantially. Completely dissimilar forms may be allomorphs of the same morpheme. The words cows, cats, pigs, horses, sheep, oxen, mice all contain the plural morpheme. Allomorphs also occur among prefixes. Their form may depend on the initial letters with which they will assimilate. For example, the morpheme in may have the following phonological forms: im occurs before bilabials – impossible; ir occurs before r – irregular; il occurs before 1 – illegal; in occurs before other consonants and vowels – inability, indirect. Morphemes can be classified semantically and structurally. From the semantic point of view morphemes are divided into root morphemes and non-root morphemes. Generally the difference between root and non-root morphemes is clearly distinguished. In the words hairless, lofty, darkness, refill the root morphemes are hair, loft, dark, fill which are understood as the lexical centers of the words, as the basic constituent part of each word without which the word is inconceivable. The root-morpheme is the lexical nucleus of a word; it has an individual lexical meaning shared by no other morpheme of the language. The root-morpheme is the morpheme common to a set of words making up a word-cluster, e.g. dance in to dance, dancer, dancing. Non-root morphemes include inflectional morphemes (inflections) and derivational morphemes (affixes). Inflections carry only grammatical meaning, they build different forms of one and the same word, e.g. cheap, cheaper, cheapest. Affixes supply the stem with components of lexical and lexico-grammatical meaning. They are classified into prefixes and suffixes, e.g. chain – unchain, broad - broaden. A suffix is a derivational morpheme which follows the stem. A prefix is a derivational morpheme which precedes the root. From the structural point of view morphemes fall into: free morphemes, bound morphemes, semi-free (semi-bound morphemes). A free morpheme is defined as one that can occur by itself as a whole word, e.g. cloudy – cloud, excusable – excuse. A great number of root morphemes are free morphemes, e.g. child in the words childhood, children, childish is naturally qualified as a free morpheme because it coincides with one of the forms of the noun child. A bound morpheme is attached to another and is a constituent part of a word. Bound morphemes are of two types: inflectional morphemes and derivational ones. Examples of inflectional morphemes can be plural morphemes watch – watches, morphemes indicating past tense look – looked, etc. Derivational morphemes are affixes, e.g. -ness, -ship, -ize, dis-, de- in the words like happiness, relationship, to displease, to demoralize. Semi-free or semi-bound morphemes can function in a morphemic sequence both as an affix and as a free morpheme, e.g. half-ready, seaman, womanlike. According to the number of morphemes words fall into monomorphic and polymorphic. Monomorphic or root-words consist of only one root-morpheme, e.g. long, car, make, drive, etc. All polymorphic words according to the number of rootmorphemes are classified into two subgroups: monoradical or root words and polyradical words, i.e. words which consist of two or more roots. Monoradical words fall into two subtypes: 1) radical-suffixal words, i.e. words that consist of one root-morpheme and one or more suffixal morphemes, e.g. digestible, blackish; 2) radical-prefixal words, i.e. words that consist of one root-morpheme and a prefixal morpheme, e.g. reconstruct, unzip; 3) prefixo-radical-suffixal, i.e. words which consist of one root, a prefixal and suffixal morphemes, e.g. unpredictable, misunderstanding. Polyradical words are grouped into two subtypes: 1) polyradical words which consist of two or more roots with no affixational morphemes, e.g. brand-new, eye- ball, bus-stop; and 2) words which contain at least two roots and one or more affixational morphemes, e.g. nut-cracker, wedding-pie, penholder. 2.4. Types of Morphemic Segmentability There are three types of morphemic segmentability: complete, conditional and defective. Complete segmentability is the characteristic feature of many words. The morphemic structure of the words with complete segmentability is transparent. The individual morphemes are clearly singled out within the word and can easily be isolated. The transparent morphemic structure of the segmentable words is conditioned by the fact that their constituent morphemes are met in other words with the same meaning, e.g. speechless – two morphemes: speech and less. The morpheme speech can be found in a speech, speeches, and the morpheme less – in words nameless, useless. Such morphemes can also be called full morphemes. Conditional segmentability is characteristic of words whose segmentation into the constituent morphemes is doubtful for some semantic reasons, e.g. retain, contain, detain. The words can be split into the following re–tain, con–tain, de–tain. The constituent part -tain unites these three verbs, but we cannot trace the common meaning in each verb, consequently we cannot regard -tain as a morpheme. Similarly we may find re-, con-, de- in other verbs (recall, remind, consist, confuse, delay, defeat), but each group of words does not share a common meaning. The morphemes making up words of conditional segmentability do not reach the status of full morphemes for semantic reasons and that is why a special term is applied to them in linguistic literature: such morphemes are called pseudomorphemes or quasi-morphemes. It should be mentioned that there is no unanimity on the question, and there are two different approaches to the problem. Those linguists who recognize pseudo-morphemes, i.e. consider it sufficient for a morpheme to have only a differential and distributional meaning to be isolated from a word regard words like retain as segmentable; those who think it necessary for a morpheme to have some denotational meaning qualify them as nonsegmentable. Defective segmentability is the property of words whose constituent morphemes are seldom or never met in other words. One of the constituent morphemes of these words is a unique morpheme. A unique morpheme is isolated and understood as meaningful because the constituent morphemes display a more or less clear denotational meaning. In the word cranberry there are two morphemes: cran and berry. The morpheme -berry occurs in strawberry, blackberry, etc. Cran that is left after the isolation of the morpheme -berry does not recur in any other English word, thus, this morpheme is unique. In conclusion, on the level of morphemic analysis linguists have to operate with two types of elementary units, namely full morphemes and pseudomorphemes. From the point of view of the complexity of the morphemic structure all English words fall into two large classes: 1) segmentable words, allowing of further morphemic segmentation, e.g. quickly, fearless, agreement, 2) non-segmentable words, e.g. house, girl, orange. Morphemic analysis deals with segmentable words. The main aim of the morphemic analysis is to split a word into its constituent morphemes, determine their number and type. The method applied for morphemic analysis by linguists is called method of immediate and ultimate constituents. This method is based on a binary principle, i.e. at each stage of the procedure the word immediately breaks into two components. These two components are considered as the immediate constituents (ICs). Each immediate constituent at the next stage of analysis is in turn split into two smaller meaningful elements. The analysis is completed when we reach constituents incapable of further division, i.e. morphemes. These morphemes are considered as the ultimate constituents (UCs). The noun disagreement, for example, is first segmented in to the immediate constituents disagree recurring in disagreed, disagrees and the ment found in nouns, such as development, judgment statement. The immediate constituent -ment is at the same time an ultimate constituent of the noun, as it cannot be broken into any smaller elements possessing both sound-form and meaning. The immediate constituent disagree is next broken into the immediate constituents dis- and -agree recurring in disarm, disapprove, disbelieve, etc., on the one hand, and agrees, agreeing, agreed, etc., on the other. Questions for Revision 1. What aspects are usually concerned by defining a word? 2. What is the difference between a word and a lexeme? 3. What two big groups are words classified into? 4. Why is one group called open and the other closed? 5. What is a morpheme? 6. What is meant by the term allomorph? 7. What types of morphemes can be singled out structurally? 8. What types of morphemes can be singled out semantically? 9. Can you differentiate between an inflectional morpheme and a derivational one? Illustrate them with the example. 10. What types of morphemic segmentability are distinguished? 11. What is a unique morpheme? Can you think of an example of a unique morpheme in Russian?