Canterbury Pony Club - Carolina Region Pony Clubs

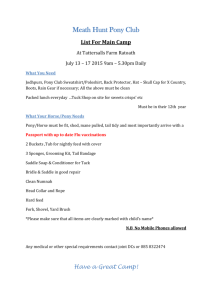

advertisement