Callanish

advertisement

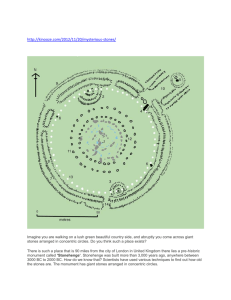

Callanish Investigations The Main Setting A Ritual Landscape Interpretations Callanish stands a low ridge at the head of Loch Roag, a long, sheltered sea-loch on the Atlantic coast of the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides. The site looks over a watery landscape dotted with small islands and surrounded by low hills. It is easily accessible by boat and a natural meeting place for people from miles around. All over the shores of the loch, within sight of the main centre, are smaller monuments—stone rings and rows as well as solitary monoliths—which look as though they were set up by visitors who got together to celebrate. Callanish: View from the North These pilgrims need not have been strictly local, for Lewis was a vital stopover on the sea lanes from Ireland and southern Britain to the Orkneys. Imported Irish axes have been found on the island and there was clearly an exchange of ideas as well. Callanish is a hybrid site as well as a very complex one, and is second only to Stonehenge when it comes to theory and speculation. Generally, the megalithic rings that are found scattered over much of western Scotland are similar to those found in the rest of Britain, especially the ones in the Cumbrian Lake District. In the Western Isles, however, the rings are more varied in design and tend to have more features—multiple, concentric rings, outliers, stone rows and centre stones. They are much smaller and tidier than the mainland examples and more likely to contain burials. They also tend to be found in clusters, such as the small group at Machrie Moor on Arran. Many of these features are also found in Ireland. Today the islands of the Outer Hebrides are thinly populated and there are large tracts of open moorland. The climate is rather cool, windy and wet, and the landscape is covered with peat. When the first people arrived on the scene, conditions were somewhat milder and much of the land was still covered with mixed forest—mainly birch and pine with some stands of oak and elm. Even so, conditions were already beginning to deteriorate. Increased rainfall coupled with poor drainage meant that much of the interior was becoming waterlogged. The trees began to die but the lack of oxygen prevented decomposition and a thick oozing mat of organic material blanketed large areas. The peat was so acidic that only the toughest scrub could grow. Settlements, such as Eilean Domhnuill on North Uist, were small and close to the water where there was access to a variety of marine resources, good grazing for their livestock and suitable soil for cultivation. Although only a few such domestic sites have been uncovered, their presence is marked by megalithic tombs similar to those found in the rest of Scotland. Investigations Early visitors to Callanish report that the locals called the stones the Fir Bhrèige ("false men") who stood under the spell of an enchanter. What they saw was a ring of stones around a tall monolith protruding from the peat with rows of stones running to the east, the west and the south. The main approach was from the north and was marked by a long, stone-lined avenue. There were the inevitable associations with the Druids but no real work was done on the site until 1857 when Sir James Matheson ordered it to be cleared of the five feet or so of peat that covered the site. His workmen uncovered a small chamber tomb within the circle and a couple of fallen stones, which have since been re-erected. Proper excavation of the site did not occur until 1980 when it was clear that it was badly in need of restoration and repair. These were conducted over two seasons by Patrick Ashmore of Historic Scotland. The central ring and tomb were thoroughly investigated and a number of trenches were opened up along the stone rows and avenue. Sketch of Callanish in 1857 by James Kerr The Main Setting Apparently the site was unoccupied prior to the construction of the monument, although traces of a circular enclosure, perhaps a corral, and some raised beds on which barley was grown. Construction began about 3000 BC with the laying out of the central setting-the ring of thirteen stones and the central monolith. Callanish: Aerial from the Southwest The stones were all Lewissean gneiss, the oldest rocks in the British Isles, distinguished by their fine, meandering lines of quartz. The central stone, at 4.75 metres, was the tallest—the rest range between 2.5 and 4 metres in height. The ring, which measures 13.4 x 11.8 metres, is not a true circle but it is symmetrical. The western half is an accurate semi-circle while the eastern half is flattened somewhat. Perhaps this was done to focus attention towards the east during ceremonial activities. The stones were set into shallow sockets that had been prepared for them and packed with pebbles and clay for additional support. Callanish: Plan of Excavations Central Setting Callanish: Centre Stone and Grave The centre stone is actually about 1.2 metres northwest of actual centre point, at the back of a small chamber tomb. The latter, a small version of the stalled cairns found in northeastern Scotland and Orkney, is clearly later than the ring but how much later is unclear. The cairn was horseshoe-shaped and had an outer revetment wall of horizontal slabs. he burial chamber was sub-divided into 'stalls' by upright slabs projecting from the walls and produced some fragments of cremated bone when it was excavated in 1857. The latest excavations produced some potsherds, found in a layer of greasy black earth outside the tomb. Ashmore believes that this was the residue of burials that had been removed from the burial chamber once the flesh had decomposed. The tomb was apparently in use for several centuries judging from the pottery, which includes both Grooved Ware and Beaker vessels, found outside. Chamber Tomb Callanish: Avenue from the south Running NNE from the circle is an avenue 83 metres long-two rows of orthostats, not strictly parallel but diverging slightly until they terminated in two higher stones set at right-angles to the others. Recent excavations have uncovered an empty stone socket near the north end of the west side of the avenue, suggesting a total of (perhaps) sixteen stones on each side. The stones of the western side of the avenue are taller than those on the eastern side—a feature also characteristic of many Irish double rows. A single row of four stones ran due west for 9 metres while another ran roughly ENE for 15.4 metres. In 1981, a fallen stone was found at the end of the eastern row of stones. West Alignment & Central Setting The socket for the latter was also discovered and the stone has since been re-erected, making five altogether. Running south for a distance of 22 metres is another row of five stones, which may have been intended as the eastern side of another avenue. If that was the case, the builders never got further than erecting a single stone on what would have been the western side. West Alignment Overall view from the South South Alignment & Central Setting A Ritual Landscape View from Cnoc Fhillibhir Bheag to Callanish with Cnoc Ceann a Ghàrraidh in the middle distance. Callanish is the largest of a number of contemporary monuments around the shores of the loch. Cnoc Ceann a Ghàrraidh is an oval ring (ca. 22 x 19 metres) consisting of five standing and three fallen stones located about a half a mile away from the main site. A rough cairn and pebble-lined sockets for at least five posts were found inside it. Just uphill is Cnoc Fhillibhir Bheag, where eight stones were found in the circuit of a slightly smaller ring (ca. 13 metres across) and another four in the centre. Several fallen stones were discovered in the course of excavations. Less than a mile north Cnoc Ceann a Ghàrraidh of Callanish is a fallen ring of eleven stones known as Na Dromannan while two miles to the south is the small ring of Ceann Thulabhaig, which also contained a cairn. In addition, there are several stone rows and individual standing stones within a mile or two. That these peripheral sites were associated with Callanish proper seems obvious but the nature of their relationship is unclear. Map of the Callanish Region Ceann Thulabhaig Interpretations Astronomers have had a field day interpreting Callanish. It has been suggested that the north avenue was directed toward the rising of Capella in about 1800 BC; that the western row was aligned with the sunset on the equinoxes; and that the eastern row pointed towards the Pleiades (in 1750 BC) or to the rising of Altair (in 1760 BC). However, it must be pointed out that the avenue also marks the natural approach to the site from the shore and is far too broad to be used as a sightline. The eastern row is not especially straight and it is difficult to imagine it being much use to prehistoric astronomers. In any case, Altair is so faint when it rises that it would have been barely visible. Gerald Hawkins emphasised the importance of the lunar cycle and suggested that the southern row was oriented towards the line of hills, Cailleach na mòitich, where the moon skipped along the horizon every 18 or 19 years. In the northern hemisphere, this phenomenon only occurs at this particular latitude (58 º). In short, while we have convincing cases for solar and lunar events, the idea that the site was a prehistoric observatory is not particularly convincing. The Classical historian, Diodorus Siculus, may have been describing Callanish when he wrote, This island...is situated North and is inhabited by the Hyperboreans... And there is also on the island both a magnificent sacred precinct of Apollo and a notable temple which is adorned with many votive offerings and spherical in shape.... They say that the Moon, as viewed from this island, appears to be but a little distance from the Earth and to have upon it prominences like those of the Earth, which are visible to the eye. The account is also given that the God visits the island every nineteen years, the period in which the return of the stars to the same place in the heavens is accomplished. At some time around the middle of the second millennium BC, the site was abandoned and apparently vandalized by the Bronze Age farmers who now populated the district. To them, the site was evidently still a place of great power