A Cultural History of Circumcision in America

advertisement

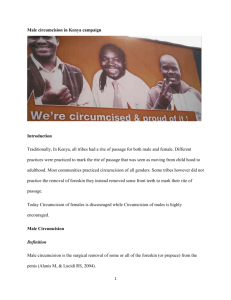

A Cultural History of Circumcision in America Circumcision of infant males in modern Western countries has generated an enormous amount of fiery controversy. Associations of medical professionals, psychologists, public health experts, and a host of citizen groups have organized to both defend and condemn the practice and the medical establishment that has made it routine. It has been studied by physicians, theologians, ethnologists, students of government, sexuality and psychology. Where there are heated social debates, there are simmering cultural anxieties beneath. And wherever broadly shared anxiety is evident, rich history can be written. My proposed program of study for the SSHRC – a subject wholly distinct from my doctoral thesis, described below – aims to bring coherence to the contests surrounding circumcision in America since the early nineteenth century by understanding the place of Jewishness in these social tensions. My methodological approach is to conceptualize circumcision as a cultural practice and a ritual rather than a medical surgery, something no student of circumcision in America has adequately done. Instead of adjudicating between intensely held moral, religious and ideological positions among the debaters, my task will be to make sense of why circumcision generated so much tension, and account for how it became a battleground. More specifically, my goal is to capture and analyze the perennial but shifting debates around (1) ethics, (2) public hygiene, (3) religious tolerance, and (4) sexuality that have, in different times and for different reasons, focused on this highly charged and somewhat taboo “site” (more accurately a non-site, the absent foreskin). It will also be to accurately describe how Jews and Jewishness have factored among these public debates. On the one hand, experts in the fields of medicine, psychology, law, ethics, theology, and civics, along with journalists, parent groups and non-experts have debated circumcision repeatedly and thoroughly since the early nineteenth century (and long before then, outside America). The debates appear repetitive, irresolvable and intractable. Yet on the other hand, the reasons advocates and detractors have articulated for and against circumcision reflect ideas that have changed dramatically over time about what is truly at stake in the practice. What appears to be clear-cut – the surgical removal of the foreskin – is in fact a shifting field of contested meanings. Circumcision itself is the site of impassioned controversy, and – not unlike abortion in the United States – it both magnifies and telescopes cultural anxieties. My research will thus bring two bodies of primary sources together: first, the scholarly literature on Judaism and circumcision, and second, the mix of polemic, medical and ethical debates around hygiene, immigration, race, citizenship, sexual pleasure, moral relativism and cultural diversity. Judaism, it seems from my preliminary research, was thrust to the centre of these debates. In response, Jews chose to intervene in them in ways they hoped would defend their ethnic particularity and simultaneously maintain the fragile sense of belonging they enjoyed amidst the scientific and moral mores of the broader America in which they lived. Unwittingly, Jews appeared in nearly every turn in circumcision’s social history over the last century. A Cultural History of Circumcision in America A body of scholarship already exists on circumcision as a social practice.1 Robert Darby has produced an excellent study of circumcision in England.2 Robin Judd and John Efron have both considered circumcision in the German context.3 I take these studies as model for my own. Parallel to this scholarship, Jews have written another not- always scholarly literature about the nature and meaning of ritual circumcision largely for Jewish audiences.4 Yet virtually no scholarship exists that deals directly with the “Jewish question” amidst public circumcision debates in America.5 In fact, no serious scholar has studied circumcision as far-reaching social and ritual practice in the American context whatsoever. My proposed work, in addition to being significant, new and frankly fascinating, will also challenge a pervasive Euro-centrism that burdens much of Jewish Studies. It is simply not the case that the tangled experience of modernity for Jews in America was “more or less” like the German experience (nor that the Canadian Jewish experience was more or less like the English). The terms of the debates, the social position of Jews in their national, economic and cultural contexts, and most importantly the outcomes of struggles were markedly different. So while studies like those of Judd, Efron and Darby’s will be useful, they cannot stand in for a work of scholarship on American circumcision grounded in as-of-yetunexamined primary archival sources. A terse chronology of circumcision debates based on my preliminary research reveals Jewishness at every turn. Many early nineteenth century American mentions of circumcision were focused on the theme of “savagery.” Observers noted that some American Indian tribes circumcised their boys, just as had the ancient Israelites. The first circumcision discussions in America then, were offered as “proofs” of the claim that Indians descended from the Lost Tribes of Israel. The stakes of these discussions had little to do with the ritual or the surgery. Rather, discussion about circumcision advanced the belief that many early 19 th century Americans had regarding the Divinity of the New World’s colonization. During the Second Great Awakening with the rise of Evangelicalism, Christians critiqued circumcision as atavistic Hebrew savagery to be “superceded” by Pauline ideas about “circumcised hearts.” 1 Please see the attached Bibliography for the most significant works, few of which treat circumcision historically. Notable from an ethnological and psychological perspective is the pioneering work of Bryk, Felix. Circumcision in Man and Woman: Its History, Psychology, and Ethnology. Translated by David Berger. New York, American Ethnological Press, 1934 [1974]. Also notable is Kathleen Biddick’s work of cultural theory, Biddick, Kathleen. The Typological Imaginary: Circumcision, Technology, History. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003. 2 Darby, Robert, A Surgical Temptation: The Demonization of the Foreskin and the Rise of Circumcision in Britain. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005. 3 Judd, Robin, Contested Rituals: Circumcision, Kosher Butchering, and Jewish Political Life in Germany, 1843-1933. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2007; Efron, John M. Defenders of the Race: Jewish Doctors and Race Science in Fin-de-siècle Europe. New Haven: Yale University Press 1994. 4 See for example, Cohen, Shaye J. D. Why Aren't Jewish Women Circumcised?: Gender and Covenant in Judaism. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005; Kunin, Samuel A. Circumcision: Its place in Judaism, Past and Present. Isaac Nathan Publishing Co. Los Angeles, 1998; and Wyner, Elizabeth Mark (ed.) The covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite. Hanover, N.H.: Brandies University Press, published by University Press of New England, 2003. 5 Leonard Glick’s Marked in Your Flesh: Circumcision from Ancient Judea to Modern America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005, is more of a celebratory and polemic work than a work of critical history. As study spanning some 4,000 years, it understandably devoted scant attention to historical detail. A Cultural History of Circumcision in America The debate had shifted from the cosmic significance of colonialism, to a racial and religious question, namely, how Christian would the new nation be. As the century came toward a close, medical experts began circumcising infant male patients believing it a prophylactic against a host of diseases, mental disorders, the spread of venereal disease, and even masturbation, considered by many “a social sickness.”6 Medicalized circumcision was born precisely as American anxieties peaked with the tide of millions of Eastern and Southern European immigrants, many of them Jews, flooded America. 7 With nativist fears of ethnic difference and degeneration, circumcision – the Jewish mark of difference – became a public health matter. With immigration halted, and high modernism competing with economic depression in the wake of the Great War, circumcision had shifted once again. By the 1920s, circumcision became the mark of social class for it indicated having been delivered in a hospital by a physician. Routine hospital circumcisions of newborn males steadily rose to approximately 70% from the end of World War II until the 1970s (a rate far higher than those in other developed countries), a time when Jewish doctors enjoyed the peak of their power in the medical establishment. Did American Jewish doctors in effect circumcise American boys so as to render their mark of difference invisible? By the 1980s and 1990s, with the explosion of discussion around ethnic diversity, corporate identity and multiculturalism, debate about circumcision reached new peaks. The emergence of numerous advocacy groups, feverish public criticism of circumcision, and the admission of circumcision cases in local and national courts all signaled the newest shift in the meaning of circumcision. The debate, while often couched in medical terms, is now focused on questions about children’s rights and the limits of ethnic particularism in ethical democracies. Jews and Muslims are now the case studies of multicultural flexibility. For all intents and purposes, my proposed research is distinct from my doctoral research. My dissertation, entitled The Jews’ Indian: Native Americans in the Jewish Imagination and Experience, 1845 – 1945, analyzes a wide range of social, cultural, political and economic encounters between Jews and Native Americans. It argues that American Jews used their engagements with both the imaginary “Indian” and the real Native Americans they encountered as frontier settlers, peddlers and traders, to work out central questions about their own place in American society as white, yet somehow different. I will defend my dissertation and earn my PhD from New York University’s departments of History and Hebrew & Judaic Studies in late January 2011. My graduate training in American religious history, in modern Jewish history (PhD), and the anthropology of medicine (MA, University of Toronto) positions me well to advance my proposed research. While my dissertation research, publications, and archival notes cannot and will not be used for any part of my proposed research on circumcision, there are some important continuities between my current scholarly project and my proposal. Like my dissertation, my SSHRC research will unpack how ideas about masculinity and ethnicity become intertwined in public consciousness and how tensions at these intersections get played out on human bodies. Furthermore, a scholarly consideration of circumcision continues my work on how Jews negotiated their place in a landscape both welcoming and hostile to their difference. Finally, methodologically, these two studies will share a common interest in bringing 6 Laqueur, Thomas Walter, Solitary Sex: A Cultural History of Masturbation. New York: Zone Books, 2003. 7 “From Ritual to Science: The Medical Transformation of Circumcision in America,” David L. Gollaher. Journal of Social History, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Autumn, 1994), pp. 5-36. A Cultural History of Circumcision in America together approaches and questions from social and cultural history, drawing from my graduate training in both history and anthropology. I will achieve my proposed research in several clearly defined stages. First I will devote several months of intense research at archives of various medical organizations,8 hospital and governmental medical reports, pro- and anti-circumcision advocates,9 the published and unpublished works of communal organizations including the Jewish ones who stake a claim in the circumcision debates. Second, I will compare this material with the published record the medical journals, books and articles by public health officials, reformers, religious advocates, psychiatrists, nurses, the popular and immigrant presses (in English and Yiddish), as well as popular cultural texts (films, memoirs, and novels). Next, I will carefully select and use this body of primary and secondary sources to analyze the meanings and anxieties that have been focused on circumcision and to set it within its most appropriate broader historical and social contexts. I intend to present my work-in-progress at the general meetings of the Canadian Congress for the Humanities & Social Sciences, the American Historical Association, and the Association for Jewish Studies in order to hone my argument and dialogue with other scholars in this interdisciplinary field. I expect this research to lead to the publishing of a book or a series of articles in peer-reviewed journals. I have selected the University of Toronto for my research for several reasons. First and foremost, Derek Penslar, the Samuel Zacks Professor of Jewish History and the co-editor of Jewish Social Studies, is among the most esteemed and rigorous historians of modern Jewry. He and I have had an ongoing relationship for several years and I believe I will benefit enormously from his mentorship as I transition from doctoral scholarship to faculty member. Furthermore, the University of Toronto is home to the Centre for Jewish Studies, arguably Canada’s finest academic hub of Jewish Studies, which along with the History department, has expressed its enthusiasm and support for my project and has invited my involvement in its scholarly activities should I be awarded a SSHRC grant. Finally, there are nearly a dozen faculty members in the Departments of History, Anthropology and the Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology at the University of Toronto whom I believe would be interested in extending me support and guidance. I would be honoured to advance the vision and goals of the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada by pursuing this scholarly work on the social and cultural history of circumcision in America in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and grateful for your consideration. Most centrally, Harvard Medical School’s Countway Library, the National Library of Medicine in Bethesda, MD, and the Biomedical Library at the University of California, San Diego. 9 These groups include the National Organization for Circumcision Information Resource Centers, the International Coalition for Genital Integrity, Doctors Oppose Circumcision, and Attorneys for the Rights of the Child. 8 A Cultural History of Circumcision in America