Preserving Florida`s HeritageMore Than Orange Marmalade

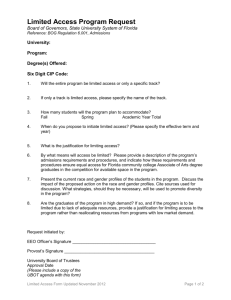

advertisement