Sergei Bulgakov: Between Two Worlds in Sophia

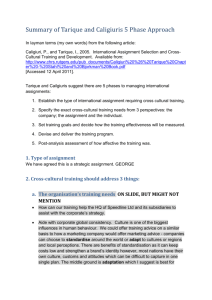

advertisement