Political Consciousness and National Identities in the Latin

advertisement

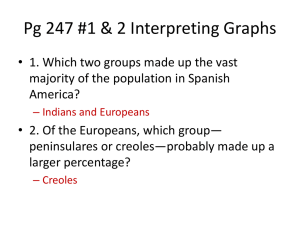

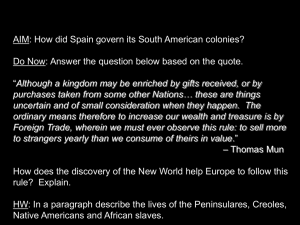

Political Consciousness and National Identities in the Latin American Struggle for Independence, 1808-1826 Federico Sor This paper comprises three parts: a summary of a lecture given by Seth Meisel on nationalist discourse during the Spanish-American independence movements (pages 1-3); an interview to Meisel after the lecture (4-6); and my commentary, which intends to deconstruct nationalist rhetoric and question the way we understand it—an ambitious undertaking indeed (7-13). I. The Lecture1 Spanish-American wars of independence, led by Creoles (Americans of European ascendance) were the first stage of national liberation. The enlightened ideals of democracy and self-determination served as ideological justification for the Creole insurrection against Spain. Napoleon’s 1808 seizure of the Spanish Crown and the subsequent legitimacy crisis of Spanish rule provided the ripe situation for the insurrection. Creoles had been conscious of the possibility of liberation since before the beginning of the Wars of Independence. For example, in 1806 and 1807 local forces defeated British troops invading the city of Buenos Aires. At this time, Creoles and slaves under the leadership of local leaders such as Santiago de Liniers and Cornelio Saavedra2 had demonstrated that they could protect their land without Spanish intervention. Moreover, this event signified that, if they could defeat the British invasions on their own, they could well put an end to Spanish colonial rule. Although the Wars of Independence were primarily a Creole movement, its enlightened ideological legitimation opened spaces of political negotiation previously nonexistent. While 1 This is the summary of a lecture given by Seth Meisel, professor of history at Yale University. The lecture was delivered on December 6, 2000 at a Latin American history survey course taught by Daryle Williams at UMCP. 2 In fact, Saavedra was a peninsular (born in Spain). Creoles sought freedom from a Spanish rule which (especially after the mid-eighteenth-century Bourbon reforms implemented by Charles III) virtually excluded them from administrative posts beyond local municipalities (cabildos), Indians and blacks adopted the ideals of independence to broadly challenge colonial hierarchies—including the hegemony of the Creole land-owning class. At this time, slaves sought their freedom through their military service to the patria and by means of legal petitions. Significantly, the latter were largely based on the same ideas of equality promoted by Creoles to justify independence. Thus the ideological rearticulations and political instability of the time provided the context for blacks and Indians to promote their own cause for freedom and equality, and the fact that they adopted the independence rhetoric to their own struggle demonstrates the political consciousness3 of the oppressed classes. As Camilla Townsend argues, the shift of power from the Spanish Crown to local Spanish-American governments, contrary to the claims of the revisionist view of independence, actually enhanced the political consciousness of "common people."4 This author analyzes the case of Angela Batallas, a Guayaquil slave woman, who appealed to independence values and the patriarchal social system to further her legal battle for freedom. In clear reference to the enlightened human equality rhetorically employed by Creoles to legitimize the struggle for independence, Angela Batallas argued that independence was incomplete if it did not abolish slavery, and she pointed out the irony in a struggle to end colonial bondage which, at the same time, perpetuated internal oppression. Referring to her unfulfilled union with a white Creole (and his unfulfilled promise to grant her freedom), she portrayed the emerging republic as a body that was only half free. In addition to the egalitarian discourse, Batallas appealed to the values of a traditionally paternalistic society as she appealed to Simón Bolívar, the Venezuelan Libertador, for protection. I use this term advisedly; ‘consciousness’ here refers to its primordial meaning, ‘awareness’ (in this case, political), and should not be equated with Marxist class consciousness. 4 "‘Half My Body Free, the Other Half Enslaved’: the Politics of the Slaves of Guayaquil at the End of the Colonial Era," Colonial Latin American Review 7.1 (1998): 105-128. This article was the required reading for the lecture. 3 Creole leaders promoted a national identity beyond internal divisions, and this discourse opened another space of negotiation for blacks and Indians. Argentine General José de San Martín stated in 1821 that "in the future the aborigines shall not be called Indians or natives; they are children and citizens of Perú and they shall be known as Peruvians."5 Meisel argued that San Martín’s pronunciation marked a shift in the conception of the social role of ‘Americans’; they had been subjects thus far, and now they were to become citizens. Indians and blacks could now appeal to this common identity in order to assert their equality. Meisel warned that slaves, in adopting the political discourse of independence, demanded their liberty individually but did not, in general, challenge slavery as an institution. Creoles promoted patriarchal self-representations (later perpetuated in the myth of the "founding fathers") to legitimize their hegemony; slaves adopted these very representations to their own struggle for freedom—like Angela Batallas, they appealed to Creoles as paternalistic figures that could grant them liberty.6 5 John Lynch, The Spanish-American Revolutions, 1808-1826 (New York: Norton, 1973), 276, as cited in Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1983), 52. 6 For Meisel’s commentary on the role of patriarchal discourse as both constructed by Creoles and adapted by slaves, see question 3 in the Interview. II. An Interview with Dr. Meisel7 1. If we accept that slaves did not attack slavery as an institution, or institutionalized racism, but rather sought to attain their individual liberty through the adoption of Creole political discourse, is it possible to talk of a ‘political consciousness’? Meisel argued that racial solidarity was the exception rather than the rule in colonial societies. There was not sufficient cohesion among slaves that would make possible a concerted struggle for the abolition of slavery. It is true, then, that slaves’ military service for the patriotic cause may have been a strategy to gain their freedom. A great level of desertion in the insurgent armies seems to back this claim. In a similar way, slaves’ petitions, which appealed to nationalism and equality, served the slaves’ own cause. But was this just a strategy? Slaves may indeed have used political discourse as a strategy for their own struggle, but their adherence to the universal equality promoted by the independence movement may have surpassed just their struggle for individual liberty. So Meisel asked, "why not believe" that they actually supported the cause of independence beyond immediate objectives? Why not believe, then, that they did develop a political consciousness compatible with the ideological foundations of the wars of independence? Military service led slaves to assert their honor, so important in the Spanish tradition. In a way, the fight for independence provided a space for political ideas to shape the political discourse of the oppressed. 2. Can we understand post-Independence civil wars in most emergent Latin American ‘nations’ as resulting from the contradictions of nationalist rhetoric during the Wars of Independence? During the Wars of Independence there was a revision of stereotypes (especially concerning ‘morality’), exemplified by the image of slaves in uniform; now slaves claimed honor for themselves on behalf of their military service. The internal tensions and contradictions of the 7 This interview was conducted by the present author and Marisabel Villagómez immediately after the lecture. I must thank Dr. Meisel for the time that he dedicated to answering our questions. For lack of a tape recorder, it has been necessary to paraphrase his responses on the basis of notes, which I have done as accurately as possible. independence period led to the chaos that characterized the first fifty years after independence. The ‘fathers of independence’, like San Martín, died in exile, and this signals the crisis of the patriarchal system and the failures of independence. During the fight for independence, individual liberties had comprised the political focus. By the 1860s, ‘order’ became the political priority, and there was a resurgence of authoritarian governments throughout Latin America. 3. Does the Creoles’ self-representation as fathers imply an equation of family and state (the larger family), of private and public spheres? Does their quest for legitimacy, in a way, provide a historical continuity with the Roman republic, specifically the presentation of the pater familias as the legitimate ruler during the Roman Republic and the rise of the Empire? In general terms, can we think of the patriarchal approach to political power in an emergent republic as legitimized by its precedent in antiquity?8 The image of a good father as the model for a republican citizen was prevalent in Spanish America during independence. The discourse that presented Creoles as a patriarchal (rather than oppressive) class was both imposed on and accepted by the lower classes. If Creoles were to take the role of fathers, they must then be fathers who respect the rights of slaves as citizens in the new nations. Creoles asserted the legitimacy of their political authority by presenting themselves as the descendants of the Spanish ‘civilizers’ and the inheritors of colonial hierarchy. At the same time, however, the family in the period of independence was in crisis. The independence struggle created divisions within families, as fathers and sons fought in opposite sides--besides more general divisions among Creoles based on fights over ‘honor’. This had consequences in the broader political system. For example, Juan Manuel de Rosas, the caudillo of the Province of Buenos Aires in the post-independence period, was deemed an ‘unnatural father’. This led to a challenge of patriarchal society, based on republican ideas. The traditional 8 We are well aware that historical parallels are swampy terrain. But the present question is justified if we remember that Bolívar, for example, had been educated on ancient Western literature. The models that he and other independence leaders adopted may not, after all, have been fortuitous. hierarchy was subverted by the formation of associations (brotherhoods) with a stress on horizontal rather than vertical relations.9 The Generation of 1837 in Buenos Aires was an example, from which writers and political thinkers arose in opposition to the patriarchal Rosas. The image of the father as having legitimate republican authority was certainly present in the struggle for independence and its aftermath. However, we cannot talk of a cultural continuity proper, as the idea of fatherly legitimacy is dubious when we take into account familial disruption and broad opposition to figures who, like Rosas, sought legitimacy by projecting the image of fathers of the nation. 4. Is the twentieth-century phenomenon of populism, in a way, a revival of the patriarchal (or paternalistic) society in the form of a corporate state? Populism arises under totally different circumstances in the 1930s in Brazil and in the 1940s in Argentina. By this time, there had been a very large immigration of Europeans, and the societies in question were in the process of industrialization, so populism was a very different event. 9 Benedict Anderson has commented that the modern nation is conceived as an association of equals, in which internal social relations are closer to the relation between siblings than that between parents and children. The very concept of nation therefore challenges a patriarchal conception of society (Benedict Anderson, "How Can a Nation Be Good?," Quigley Lecture, Georgetown University, 3 November 2000). III. The Inclusion of the Excluded: Contradictions in the Creation of the Nation Meisel’s analysis of Creole rhetoric and its adaptations is extremely useful in understanding the opening of spaces of negotiations in Spanish-American societies during independence.10 While describing the Creole nationalist rhetoric seeking to legitimize the struggle for independence, however, the speaker simplified the internal tensions that collided with the successful creation of a national identity. In a way, Meisel’s argument did not seek to draw a line between the intentions and beliefs of Creoles and their rhetoric. By simplifying rather than problematizing Creole discourse, the speaker failed to dwell into the principal contradiction of national independence recognized by Creoles themselves: that the struggle against Spanish oppression by no means aimed at the equality of internally oppressed socioracial groups (most conspicuously, Indians and blacks). Internal tensions in Spanish-American societies were actually enhanced (while made explicit) by the rhetoric that characterized the struggle for independence, and these tensions have continued to shape Spanish-American history in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Therefore, deconstructing Creole nationalist rhetoric, as well as analyzing the adoption of this rhetoric by the oppressed sectors (an analysis that complements rather than opposes Weisel’s argument), is imperative for understanding the conflict in the creation of the Spanish-American ‘nations’. We should not forget that, as Benedict Anderson has pointed out, "nation-ness, as well as nationalism, are cultural artefacts of a particular kind," and that "Communities are to be distinguished, not by their falsity / genuineness, but by the style in which they are imagined."11 Accordingly, the construction of a national identity based on common history, culture and origins is determined by specific political objectives. The ‘nation’ does not have an inherent 10 The concept of a "space of negotiation" to understand the political possibilities for subaltern groups allowed by the new Creole rhetoric was brought to my attention by Marisabel Villagómez, whom I thank for it. 11 Imagined Communities, 13, 15. essence that defines it; rather, a primordial essence is constructed a posteriori to justify specific political movements seeking to be national. Nationalist rhetoric was a means by which Creoles sought to legitimize the struggle for independence. By appealing to the ‘nation’ rather than to any particular sector, Creoles could universalize the aims of independence; these objectives thus appeared as the liberation of the whole society rather than as the advancement of Creoles. Creoles did not necessarily believe to be on an equal footing with Indians and blacks; they merely sought the adherence of these groups to the struggle for independence. But by stating that a national identity existed which blurred internal divisions (as Meisel pointed out), Creoles opened the discursive space for Indians and blacks to claim their equality based on that very national identity. A comment on discourse is due. Rhetoric may be internalized over time, and the continuous assertion of equality and national identity may lead to the belief in these ideas and their materialization.12 This means that equality may result from egalitarian rhetoric, but not that egalitarian rhetoric necessarily follows from the belief in equality. The fact that Creoles argued for a national identity beyond socio-racial divisions does not mean that they believed in the artificiality of those divisions. In other words, Creoles’ appeal to equality does not imply their belief in it.13 In turn, while Indians and blacks adopted this rhetoric to reclaim their own liberty and equality, this does not mean that they believed in the rhetorical honesty of Creoles. Rather, by taking Creoles at face value and adopting the very appeals that Creoles used in their rhetoric, Indians and slaves could present their claims as legitimate.14 While this picture is undoubtedly complex, it describes the tensions inherent to a rhetorical system in which a single discourse becomes a strategy for groups in mutual opposition. 12 I do not mean to say here that a lie becomes truth if repeated enough, nor that racial equality exists, even today, in Latin American nations. 13 In a way, a corrupt government official is no less corrupt if he condemns corruption. 14 A good rhetorical strategy to remove the corrupt government official from office is to cite his/her own condemnation of corruption. The republican ideas of the Enlightenment shaped the struggle for independence in Latin America--or, more accurately, the leaders of the struggle self-consciously adopted the ideas of the Enlightenment to legitimize their cause. But adopting enlightened ideals such as the equality of men and representative government to validate the quest for independence was not without its contradictions; for example, while Creoles sought independence from Spain (their own freedom), they were reluctant to grant freedom to slaves. In this light, the enlightened discourse that stressed freedom and a common national identity should be understood and analyzed as a means of representation rather than an accurate reflection of actual social relations. San Martín's appeal to Indians as "Peruvians," implying a recognition of all locals as emergent citizens, was coherent during the independence struggle, as the leaders of the fight sought the enlistment of as many men as possible in military service. But this appeal is especially problematic, as it reacted against an actual lack of unity among "Peruvians" (a point which Meisel failed to stress). A vast number of Indians in Perú sided with (and fought for) Spain and this was the last country in continental Spanish America to attain its independence. More generally, slaves throughout Spanish America were not so supportive of the independence cause. This was partly due to the fact that the Crown had actually issued laws for a more humane treatment of slaves, which Creoles opposed.15 Given the lack of cohesion among different socio-racial sectors and the resulting limitations of the independence movement, independence leaders sought to build unity among ‘Americans’, thereby building consensus and physical support for their fight. But some of the leaders saw the contradictions in the struggle, which people like Angela Batallas pointed out. In his famous "Jamaica Letter," Bolívar recognized the ambiguities of the Creole position in the fight against Spain, as he argued that we [Creoles] are neither Indians nor Europeans, but a species midway between the legitimate proprietors of the country and the Spanish usurpers. In short, Americans by birth, we derive our rights from Europe, and we have to assert these 15 For example, the 1789 legislation. Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities, 51. rights against the rights of the natives, and at the same time defend ourselves against the hostility of the invaders.16 Creoles were in opposition to both Indians (recognized by Bolívar as rightful owners of the land) and Spain. The Libertador thus understood the internal tensions and enmities that undermined a concerted fight against Spain, as Creoles fought against Spanish oppression of Creoles but not against Creole oppression of Indians and blacks. In this light, San Martín’s talk of a Peruvian identity should be understood not as a statement of fact (that Indians, Creoles, and blacks indeed thought of themselves as Peruvians) but as part of a political program (that they should think of themselves as Peruvians). That program aimed at conciliating different social sectors under an artificially created identity.17 This identity, in turn, was based on a national18 appeal that intended to blur internal divisions (racial, regional, socioeconomic) by identifying an external enemy (Spain) in opposition to which "Peruvians" could unite. In a sense, while proposing a common identification for Indians, blacks and Creoles as "Peruvians," San Martín’s statement created a space of "false disidentification, of false distance towards the actual co-ordinates of those subjects' social existence." This process calls for a rhetorical abandonment of previous identities, but not for the subversion of the social roles that 16 Simón Bolívar, "Answer of a South American to a Gentleman of this Island" (letter to Mr. Henry Cullen of Falmouth, Jamaica, Kingston, 6 September 1815) translated in John Lynch, ed., Latin American Revolutions, 1808-1826: Old and New World Origins (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994), 308-320, 312. 17 Anderson opportunely remarks that San Martín's edict derived from the intention to define the nation around Spanish as a common language (even if Indians in Perú spoke mainly Quechua). This process of identification is comparable to (forcible) religious conversion and contemporary immigrant "naturalization." Imagined Communities, 133. 18 The emergent nations were geographically defined more or less following the Spanish administrative structures: virreinatos (viceroyalties), gobernaciones, and alcaldías. Accordingly, national appeal was grounded on each administrative structure. There is in general (not just in the Americas) an isomorphic relation between the geographical limits of nation-states (and nationalisms) and the territorial stretches of previous colonial administrative units. See Anderson, Imagined Communities, 50-65 and 105-107. those identities imply.19 According to San Martín's discourse, Indians and blacks must cease to recognize themselves as Indians and blacks to become Peruvians--without necessarily implying that Indians and blacks should, for example, cease to be peasants to become land owners or government officials. The ambiguities which Bolívar recognized in the struggle for independence (Creole freedom from Spain without necessarily ending Creole oppression of Indians and blacks) imply that the new identification was a strategy used in building support for the independence cause, but not necessarily a promise of granting internally oppressed social groups the full rights of citizens. Against Meisel, Creole rhetoric, while calling for a transformation of locals from ‘subjects’ to ‘citizens’, really implied that Indians and blacks were to cease being the subjects of Spain to become the subjects of Creoles. Creole nationalist rhetoric may thus have been mostly a strategy to achieve popular support for their cause, rather than an accurate reflection of creole ideological renewal. In turn, the slaves’ adoption of Creole discourse did not necessarily mean that slaves actually believed it. Rather, they took advantage of the space of political negotiation made possible by the new rhetoric. Slaves thus demanded liberty on the basis of Creoles’ libertarian rhetoric; slaves and Indians demanded equality on the basis of Creoles’ egalitarian rhetoric. We have seen that the discourse of both elites and the oppressed during the period of Latin American independence did not necessarily reflect radically changing views on the social roles of different social sectors, but it certainly had a specific political objective in each case. On the one hand, Creoles sought to define a national identity compatible with their quest for sociopolitical hegemony. Nationalist rhetoric sought to build broad support for the independent 19 Slavoj Zizek, "Class Struggle or Postmodernism? Yes, please!" in Judith Butler, Ernesto Laclau and Slavoj Zizek, Contingency, Hegemony, Universality: Contemporary Dialogues on the Left (London: Verso, 1999), 90-135, 103. The author here draws on Peter Pfaller, "Der Ernst der Arbeit ist vom Spiel gelernt," in Work and Culture (Klagenfurt: Ritter Verlag, 1998), 29-36. Zizek goes on to argue that the process of "false disidentification" not only fails to subvert social roles, but actually perpetuates them, as "the very distance towards the symbolic feature that determines [one’s] social place guarantees the efficiency of this determination." cause led by Creoles; republican discourse legitimized the objectives of this struggle; and patriarchal self-representations sought to validate Creoles’ political hegemony. On the other hand, the lower classes adopted Creole discourse (when they did) to benefit from the imminent political change. Slaves adopted the nationalist rhetoric to avoid exclusion in the emergent "nations" and reap the benefits of the fight for independence; they echoed the egalitarian and nationalist discourse to further their quest for personal liberty; they appealed to Creole paternalistic self-representation in order to seek individual protection within the patriarchal model. The discourse analyzed here (and its articulations by different social sectors) reflected a specific aim at sociopolitical change20 rather than a permanent transformation. This becomes clear when we analyze nationalist discourse (the Creole claim of a national identity beyond social divisions) in the light of the continuing discrimination of certain social sectors from political power. The invention of a Peruvian nation-ness was not without its long-term contradictions, if we consider the oppression of Indians which was virtually untouched (if not worsened) by independence. Against San Martín’s prediction, Indian (as opposed to ‘Peruvian’, or ‘Mexican’) identity did not disappear. Indigenismo, the pride of Indian identity developed in the early- twentieth century, is an example of the failure of the national identification. A retrospective analysis therefore leads us to the conclusion that nationalist rhetoric was, if anything, a political devise in the legitimation of the independence movement. This rhetoric opened a space of political negotiation for Indians and blacks, who adopted the very rhetoric used by Creoles to further their own cause. But although nationalist rhetoric may have served to challenge the inequalities of Spanish-American societies when adopted by the oppressed social 20 Social, political and economic change was limited by the very ambiguities of the independent cause identified by Bolívar. Therefore, we talk of sociopolitical change advisedly. Independence from Spain did not cause drastic modifications in the social pyramid—except, of course, the virtual disappearance of the peninsular elite. sectors, it did not necessarily intend to do so. In other words, Creole rhetoric originated as an instrument in the hands of Creoles and for the benefit of Creoles, but Indians and blacks used this very rhetoric to claim their freedom and equality. The rhetoric was thus a double-edge knife with unintended consequences. The weapon used by Creoles turned against them; the discourse seeking to assert their hegemony was turned, by the oppressed, into a challenge of that very hegemony.