Chapter 2

advertisement

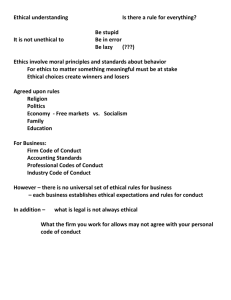

Slide 1 Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility Chapter 2 2-1 ©2007 Prentice Hall Chapter 2: Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility Slide 2 Chapter 2 Objectives After studying this chapter, you will be able to: • Discuss what it means to practice good business and explain the three factors that influence ethical behavior • Identify three steps that businesses are taking to encourage ethical behavior • List four questions you might ask yourself when trying to make an ethical decision • Explain the difference between an ethical dilemma and ethical lapse 2-2 ©2007 Prentice Hall Chapter 2 Objectives: After studying this chapter, you will be able to: Discuss what it means to practice good business ethics and highlight three factors that influence ethical behavior Identify three steps that businesses are taking to encourage ethical behavior and explain the advantages and disadvantages of whistle-blowing List four questions you might ask yourself when trying to make an ethical decision Explain the difference between an ethical dilemma and an ethical lapse Slide 3 Chapter 2 Objectives, cont. • Explain the controversy surrounding corporate social responsibility • Discuss how a business can become more socially responsible • Define sustainable development and explain the strategic advantages of managing with sustainability as a priority 2-3 ©2007 Prentice Hall Chapter 2 Objectives, cont. Explain the controversy surrounding corporate social responsibility Discuss how a businesses can become more socially responsible Define sustainable development and explain the strategic advantages of managing with sustainability as a priority Slide 4 Two Sets of Ideals Social Responsibility Ethics 2-4 ©2007 Prentice Hall This chapter explains what it means to conduct business in an ethically and socially responsible manner and discusses the importance of doing so. Many people use the terms social responsibility and ethics interchangeably, but the two are not the same. Social responsibility is the idea that a business has certain obligations to society beyond the pursuit of profits. Ethics, by contrast, is defined as the principles and standards of moral behavior that are accepted by society as right versus wrong. To make the “right choice” individuals must think through the consequences of their actions. Business ethics is the application of moral standards to business situations. This slide includes an animated image. A man in a suit is silhouetted in the back and looking off to the left. There are two cogs that appear to be rotating in order with the man’s thought process. Slide 5 What is Ethical Behavior? • Definition • Competing Fairly and Honestly • Communicating Truthfully • Not Causing Harm to Others 2-5 ©2007 Prentice Hall In business, besides obeying all laws and regulations, practicing good ethics means competing fairly and honestly, communicating truthfully, and not causing harm to others. Businesses are expected to compete fairly and honestly and not knowingly deceive, intimidate, or misrepresent customers, competitors, clients, or employees. While most companies compete within the boundaries of the law, some do knowingly break laws or take questionable steps in their zeal to maximize profits and gain a competitive advantage. Companies that practice good ethical behavior refrain from issuing false or misleading communications. According to a recent Business Week/Harris poll, some 79 percent of Americans believe corporate executives put their own personal interests ahead of workers’ and shareholders’. Placing one’s personal welfare above the welfare of the organization can cause harm to others. For instance, every year tens of thousands of people are the victims of investment scams. Insider trading is illegal and is closely checked by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Another way that businesspeople can harm others is by getting involved in a conflict of interest situation. A conflict of interest exists when choosing a course of action will benefit one person’s interests at the expense of another or when an individual chooses a course of action that advances his or her personal interests over those of his or her employer. This slide includes an image on the right of the slide showing four businesspeople sitting at a conference table. A man in a shirt and tie appears to be talking to the group. He is holding and displaying to the group a sheet of paper. Slide 6 Competing Fairly and Honestly • Trade Secrets • Industrial Espionage • Pretexting 2-6 ©2007 Prentice Hall Businesses are expected to compete fairly and honestly and not knowingly deceive, intimidate, or misrepresent themselves to customers, competitors, clients, or employees. Practices that raise ethical questions include hiring employees from competitors to gain trade secrets, engaging in industrial espionage to spy on other companies, and pretexting—essentially lying about who you are (such as posing as a journalist) in order to gain access to information that you couldn’t get otherwise. Tom Krazit, “FAQ: The HP ‘Pretexting’ Scandal,” ZDNet.com, 6 September 2006 [accessed 26 October 2006] www.zdnet.com. This slide includes a picture of four diverse and professional looking individuals. All with a stern, yet friendly facial expression. There are two females and two males. Slide 7 Communicating Truthfully • Tell the Truth, Whole Truth and Nothing but the Truth • Transparency 2-7 ©2007 Prentice Hall Today’s companies communicate with a wide variety of audiences, from their own employees to customers to government officials. Communicating truthfully is a simple enough concept: Tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. This slide includes an image of a dictionary. Over the dictionary is a magnifying glass that is focused on the word ‘honesty’. Slide 8 Not Causing Harm to Others • Insider Trading • Conflict of Interest 2-8 ©2007 Prentice Hall Specifically, buying or selling a company’s stock based on information that outside investors lack is known as insider trading, which is not only unethical but also illegal. Insider trading is a good example of the ethical trouble that businesspeople can get into when they face a conflict of interest, a situation in which a choice that promises personal gain compromises a more fundamental responsibility. This slide includes an image on the right side that is of a man in a suit dropping from the sky with a parachute. Slide 9 Corporate Fraud Adelphia WorldCom Ford and Firestone 2-9 ©2007 Prentice Hall The new millennium has ushered in a wave of fraud, investment scams, and ethical lapses unprecedented in scope. Worse yet, such corruption has cost thousands of employees their jobs, clipped investor stock portfolios by billions, and destroyed the faith of many in Corporate America and its underlying securities markets. Adelphia. For 50 years, John Rigas, the founder of the sixth largest U.S. cable company, lived the American Dream. But he and his two sons—Timothy and Michael— were accused of committing one of the largest frauds ever perpetrated on investors and creditors. WorldCom. This long-distance telecom giant shocked investors when it revealed in 2002 that it had engaged in one of the biggest frauds in corporate history. The company admitted to overstating cash flow by $3.9 billion by reporting ordinary expenses as capital expenditures. The accounting fraud allowed WorldCom to post a 2001 profit of $1.4 billion instead of reporting a loss for that year. Ford and Firestone. Faulty Firestone tires on Ford Explorers are blamed for 271 deaths and more than 800 injuries worldwide—numbers that investigators said could've been much lower if both companies had reacted sooner to evidence of product failure. Firestone blamed the problem on Ford (and on Explorer drivers); Ford blamed the problem on Firestone. Firestone refused to recall the tires, then Ford stepped in and replaced the tires on nearly 50,000 vehicles in 16 counties outside the United States— but neither company bothered to inform U.S. authorities or customers until similar failures started to show up in this country. This slide includes an image of a judge sitting at his desk with his gavel raised and what appears to be a law book that is open and in front of him on the desk. Slide 10 Corporate Fraud Enron Tyco Arthur Andersen 2-10 ©2007 Prentice Hall The new millennium has ushered in a wave of fraud, investment scams, and ethical lapses unprecedented in scope. Worse yet, such corruption has cost thousands of employees their jobs, clipped investor stock portfolios by billions, and destroyed the faith of many in Corporate America and its underlying securities markets. Enron. The most highly publicized corporate financial scandal of the new millennium involved energy-trading giant Enron and its auditors, Arthur Andersen. Company executives have been charged with grossly inflating company profits by hiding debt and engaging in numerous accounting shenanigans. The debacle damaged public trust in Corporate America, setting off a chain of governmental proposals to reform big business. Tyco. Former Tyco In 2002 CEO L. Dennis Kozlowski and former Tyco CFO Mark H. Swartz were charged with having stolen more than $170 million from the company and with defrauding investors by illegally reaping $430 million from company stock sales. Arthur Andersen. One of the world's oldest and most distinguished public accounting firms, Arthur Andersen served as both Enron's independent financial auditor and management advisor (Chapter 13 discusses this conflict of interest in more detail). The company was indicted for shredding Enron accounting documents and later convicted of obstruction of justice for hiding information about Enron finances, making it the first major accounting firm ever convicted of a felony. As a consequence, Arthur Andersen was required to stop performing public audits—the core of its business—and shed twothirds of its employees. This slide includes an image of a judge sitting at his desk with his gavel raised and what appears to be a law book that is open and in front of him on the desk. Slide 11 Ethical Business Behavior Organizational Behavior Knowledge Influential Factors Factors Influential Cultural Differences 2-11 ©2007 Prentice Hall Although a number of factors influence the ethical behavior of businesspeople, three in particular appear to have the most impact: cultural differences, knowledge, and organizational behavior. Globalization exposes businesspeople to a variety of different cultures and business practices. What does it mean for a business to do the right thing in Thailand? In Africa? In Norway? What may be considered unethical in the United States may be an accepted practice in another culture. In most cases, a well-informed person is in a position to make better decisions and avoid ethical problems. Making decisions without all the facts or a clear understanding of the consequences could harm employees, customers, the company, and other stakeholders. The foundation of an ethical business climate is ethical awareness. Organizations that strongly enforce company codes of conduct and provide ethics training help employees recognize and reason through ethical problems. Similarly, companies with strong ethical practices set a good example for employees to follow. On the other hand, companies that commit unethical acts in the course of doing business open the door for employees to follow suit. Slide 12 Be an Ethical Leader • Lead by example • Don’t tolerate unethical behavior • Inspire concretely • Acknowledge reality • Communicate • Be honest • Hire good people 2-12 ©2007 Prentice Hall Lead by example. Again, nothing is more important than demonstrating your commitment to ethics than behaving ethically yourself. Don’t tolerate unethical behavior. At the same time, you have to show that bad decisions won’t be accepted. Let one go without correction, and you’ll probably see another one before long. Inspire concretely. Tell employees how they will personally benefit from participating in ethics initiatives. People respond better to personal benefits than to company benefits. Acknowledge reality. Admit errors. Discuss what went right, what went wrong, and how the company can learn from the mistakes. Solicit employee opinion and act on those opinions. If you only pretend to be interested, you’ll make matters worse. Communicate, communicate, communicate. Ethic needs to be a continuous conversation, not a special topic brought up only in training sessions or when a crisis hits. Harold Tinkler, the chief ethics and compliance officer at the accounting firm Deloitte & Touche, says that “Companies need to turn up the volume” when it comes to talking about ethics. Be honest. Tell employees what you know as well as what you don’t know. Talk openly about ethical concerns and be willing to accept negative feedback. Hire good people. Alan Greenspan, former chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, put it nicely: “Rules are no substitute for character.” If you hire good people (not people who are good at their jobs, but people who are good, period) and create an ethical environment for them, you’ll get ethical behavior. If you hire people who lack good moral character, you’re inviting ethical lapses, no matter how many rules you write. This slide includes an image of a gentleman with a megaphone in his right hand and he is shouting toward the skies. Slide 13 The Four Questions • Is the decision legal? • Is it balanced? • Can you live with it? • Is it feasible? 2-13 ©2007 Prentice Hall The time-honored “Golden Rule” of treating others the way you want to be treated can get you into trouble when others don’t want to be treated the same way you do. You might also consider asking yourself a series of questions: Is the decision legal? (Does it break any laws?) Is it balanced? (Is it fair to all concerned?) Can you live with it? (Does it make you feel good about yourself?) Is it feasible? (Will it actually work in the real world?) This slide includes an image of a stick-figure man that has a balloon over his head with a question mark inside the balloon. The man is resting his head on his right hand and has a briefcase in his left hand. He is staring at a road sign that is offering a left turn or a right turn. Slide 14 Ethical Situations Ethical Dilemma Ethical Lapse 2-14 ©2007 Prentice Hall When making ethical decisions, keep in mind that most ethical situations can be classified into two general types: ethical dilemmas and ethical lapses. An ethical dilemma is a situation in which one must choose between two conflicting but arguably valid sides. All ethical dilemmas have a common theme: the conflict between the rights of two or more important groups of people. The second type of situation is an ethical lapse, in which an individual makes a decision that is clearly wrong, such as divulging trade secrets to a competitor. Be careful not to confuse ethical dilemmas with ethical lapses. A company faces an ethical dilemma when it must decide whether to continue operating a production facility that is suspected, but not proven, to be unsafe. A company makes an ethical lapse when it continues to operate the facility even after the site has been proven unsafe. This slide includes an image of an African American judge who is holding a law book in his right hand and extending his pointer finger on his left hand. The picture is taken from above the judge and his is looking up at the camera with glasses and a stern look on his face. Slide 15 Business and Society • Consumers expect benefits that require money. • Business generates a majority of money in a free-market economy. • Standard of living is generally derived from profit-seeking companies. • Businesses cannot hope to operate profitably without the many benefits provided by a safe and relatively predictable business environment. 2-15 ©2007 Prentice Hall Consumers in contemporary societies enjoy and expect a wide range of benefits, from education to health care to products that are safe to use. Most of these benefits share an important characteristic: They require money. Businesses operating in free-market systems such as the U.S. economy generate the vast majority of the money in a nation’s economy, either directly or indirectly. When companies pay taxes or pay for the right to use a public asset (such as a cell phone company buying the right to use part of the radio spectrum), they directly contribute to the nation’s economic well-being. When companies pay employees, those employees spend money on goods and services and pay income taxes on what they earn as well as a variety of other taxes on what they buy and own. Either way, profit-seeking companies are the economic engine that powers modern society. People who expect “the government” to pay for something need to remember that the government gets most of its income from taxpayers, both businesses and individuals. Aside from money, much of what we consider when assessing a society’s standard of living, from medication to building materials, involves goods and services created by profit-seeking companies. Conversely, companies cannot hope to operate profitably without the many benefits provided by a safe and relatively predictable business environment— talented and healthy employees, a transportation infrastructure, opportunities to raise money, protection of assets, and customers with the ability to pay for goods and services, to name just a few. Slide 16 Corporate Social Responsibility Perspectives • Minimalist • Defensive • Cynical • Conscientious 2-16 ©2007 Prentice Hall Minimalist. According to what might be termed the minimalist view, the only social responsibility of a business is to pay taxes and obey the law. In a 1970 article that is still widely discussed today, Nobel Prize–winning economist Milton Friedman articulated this view by saying, “There is only one social responsibility of business: to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.” This view, which tends to reject the stakeholder concept described in Chapter 1, might seem selfish and even antisocial, but it raises a couple of important questions. First, any business that operates ethically and legally provides society with beneficial goods and services at fair prices. Isn’t that meeting the business’s primary social obligation? Second, should businesses be in the business of making social policy and spending the public’s money? Proponents of the minimalist view claim this is actually what happens when companies make tax-deductible contributions to social causes. Assume a company makes a sizable contribution that nets it a $1 million tax break. That’s $1 million taken out of the public treasury—where voters and their elected representatives can control how money is spent—and put into whatever social cause the company chooses to support. Would it be better for society if companies paid full taxes and let the people decide how the money is spent? Defensive. Many companies today find themselves facing pressure from a variety of activists and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), nonprofit groups that provide charitable services or promote causes, and from workers’ rights to environmental protection. One possible response to this pressure is to engage in CSR activities as a way to avoid further criticism. In other words, the company takes positive steps to address a particular issue but only because it has been embarrassed into action by negative publicity. Cynical. Another possible response is purely cynical, in which a company accused of irresponsible behavior promotes itself as being socially responsible without making substantial improvements in its business practices. For example, environmental activists use the term greenwash (a combination of green and whitewash, a term that suggests covering something up) as a label for publicity efforts that present companies as being environmentally friendly when their actions speak otherwise. Ironically, some of the most ardent anti-business activists and the staunchly pro-business proponents of the minimalist view tend to agree on one point: that many CSR efforts are disingenuous. Thirty-five years after his provocative article, Friedman said he believed that “most of the claims of social responsibility are pure public relations.” Conscientious. In the fourth approach to CSR, company leaders believe they have responsibilities beyond making a profit, and they back up their beliefs and proclamations with action—without being prompted to by outside forces. John Mackey, CEO of Whole Foods Market, is a strong proponent of this view: “I believe that the enlightened corporation should try to create value for all of its constituencies,” which he identifies as customers, employees, vendors, investors, communities, and the environment. From its inception, the company has given 5 percent of profits to a variety of causes. “Whole Foods gives money to our communities because we care about them and feel a responsibility to help them flourish as well as possible.” Mackey says the minimalist view and Adam Smith’s invisible hand guiding the marketplace (see Chapter 1) are based on a “pessimistic and crabby view of human nature.” Note that his approach doesn’t have to compromise profits or returns for investors, either: Whole Foods is the most profitable large grocery chain in the United States. . Milton Friedman “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits,” New York Times Magazine, 13 September 1970 [accessed 15 June 2007] www.umich.edu/~thecore. . “Social Responsibility: ‘Fundamentally Subversive’?” Interview with Milton Friedman, Business Week, 15 August 2005 [accessed 14 June 2007] www.businessweek.com. . Milton Friedman, John Mackey, and T. J. Rodgers, “Rethinking the Social Responsibility of Business: A Reason Debate Featuring Milton Friedman, Whole Foods’ John Mackey, and Cypress Semiconductor’s T. J. Rodgers,” Reason, October 2005 [accessed 14 June 2007] www.reason.com. This slide includes an image from below looking up of a tall, modern looking skyscraper with a blue sky and puffy clouds in the background. Slide 17 Efforts to Increase Social Responsibility Social Audit Philanthropy Cause-Related Cause Cause-Related Marketing 2-17 ©2007 Prentice Hall Businesses that give back to society are finding that their efforts can lead to a more favorable public image and stronger employee morale. Thus, more and more organizations are attempting to be socially responsible citizens by conducting a social audit, by engaging in cause-related marketing, or by being philanthropic. A social audit is a systematic evaluation and reporting of the company's social performance. The report typically includes objective information about how the company's activities affect its various stakeholders. Companies can also engage in cause-related marketing, in which a portion of product sales help support worthy causes. Some companies choose to be socially responsible corporate citizens by being philanthropic; that is, they donate money, time, goods, or services to charitable, humanitarian, or educational institutions. This slide incorporates three evenly sized circles symbolizing the equal relationship between a social audit, cause-related marketing, and philanthropy. Slide 18 Reduce Pollution Industrial Discharges Vehicle Emissions Chemical Spills 2-18 ©2007 Prentice Hall Environmental issues exemplify the difficulty that businesses encounter when they try to reconcile conflicting interests: Society needs as little pollution as possible from businesses. But producing quality products to satisfy customers’ needs can cause pollution to some degree. For decades, environmentalists have warned businesses and the general public about the dangers of pollution (the contamination of the natural environment by the discharge of harmful substances). Our air, water, and land can easily be tainted by industrial discharges, aircraft and motor vehicle emissions, and a number of chemicals that spill out into the environment as industrial waste products. Moreover, the pollution in any one element can easily taint the others. For instance, when emissions from coal-burning factories and electric utility plants react with air, they can cause acid rain, which damages lakes and forests. This slide includes an image of the earth and pollution. Slide 19 Responsibility Toward Consumers • Consumerism: The right to safe products The right to be informed The right to choose The right to be heard 2-19 ©2007 Prentice Hall The 1960s activism that awakened business to its environmental responsibilities also gave rise to consumerism, a movement that put pressure on businesses to consider consumer needs and interests. Consumerism prompted many businesses to create consumer-affairs departments to handle customer complaints. It also prompted state and local agencies to set up bureaus to offer consumer information and assistance. At the federal level, President John F. Kennedy announced a "bill of rights" for consumers, laying the foundation for a wave of consumer-oriented legislation. These rights include the right to safe products, the right to be informed, the right to choose, and the right to be heard. The U.S. government imposes many safety standards that are enforced by the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), as well as by other federal and state agencies. Consumers have a right to know what is in a product and how to use it. They also have a right to know the sales price of goods or services and the details of any purchase contracts. The Food and Drug Administration, the Federal Trade Commission, and the Agriculture Department are the federal agencies responsible for regulating product labels to make sure no false claims are made. How far should the right to choose extend? Are we entitled to choose products that are potentially harmful, such as cigarettes, liquor, or guns? To what extent are we entitled to learn about these products? Consumer groups and businesses are concerned about these questions, but no clear answers have emerged. Moreover, some consumer groups say that government does not do enough. Many companies have established toll-free numbers for consumer information and feedback and print these numbers on product packages. In addition, more and more companies are establishing websites to provide product information and a vehicle for customer feedback. Companies use such feedback to improve their products and services and to make informed decisions about offering new ones. Slide 20 Responsibility Toward Investors Fair Profit Social Distribution Responsibility Ethical Behavior 2-20 ©2007 Prentice Hall Today a growing number of investors are concerned about the business ethics and social responsibility of the companies in which they invest. Aggrieved investors are filing lawsuits against the management of companies that admit to “accounting irregularities,” their boards of directors, and their audit committees. Clearly, a business can fail its investors by depriving them of their fair share of the profits. This slide includes an image of three colored and equally sized circles that shows the relationship between fair profit distribution, social responsibility and ethical behavior. Slide 21 Responsibility Toward Employees • Equal Opportunity Civil Rights Act EEOC • Affirmative Action 2-21 ©2007 Prentice Hall The Civil Rights Act of 1964 established the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the regulatory agency that addresses job discrimination. The EEOC is responsible for monitoring the hiring practices of companies and for investigating complaints of job-related discrimination. It has the power to file legal charges against companies that discriminate and to force them to compensate individuals or groups who have been victimized by unfair practices. The Civil Rights Act of 1991 extended the original act by allowing workers to sue companies for discrimination and by granting women powerful legal tools against job bias. In the 1960s, affirmative action programs were developed to encourage organizations to recruit and promote members of groups whose economic progress had been hindered through legal barriers or established practices. This slide includes an image of a two sided scale that is evenly balanced. On the left side of the scale are three men with their arms extended to their sides and parallel to the ground. On the right side are three women with their arms extended at their side and angled upward. Slide 22 Responsibility Toward Employees • People with disabilities ADA • OSHA 2-22 ©2007 Prentice Hall In 1990, people with a wide range of physical and mental difficulties got a boost from the passage of the federal Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which guarantees equal opportunities in housing, transportation, education, employment, and other areas for the estimated 50 to 75 million people in the United States with disabilities. Every year 5,000–7,000 U.S. workers lose their lives on the job and thousands more are injured (see Exhibit 2.8). During the 1960s, mounting concern about workplace hazards resulted in passage of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970, which set mandatory standards for safety and health and which established the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to enforce them . “Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities,” Bureau of Labor Statistics [accessed 12 June 2007] www.bls.gov/iif. This slide shows an image of a man with a hard hat on and a brick that has fallen on his head and bounced off. Slide 23 Global Responsibilities • Bribery • Environmental Abuse • Unscrupulous Business Practices 2-23 ©2007 Prentice Hall As complicated as ethics and social responsibility can be for U.S. businesses, these issues grow even more complex when cultural influences are applied in the global business environment. Corporate executives may face simple questions regarding the appropriate amount of money to spend on a business gift or the legitimacy of payment to “expedite” business. Or they may encounter out-and-out bribery, environmental abuse, and unscrupulous business practices. This slide includes an image of a photo of the earth and two human hands cradling the earth.