Example 4 (several persons, utterances, arguments and rebuttals)

advertisement

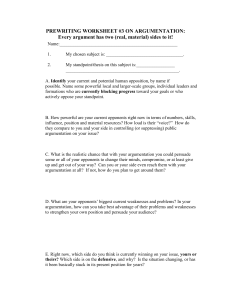

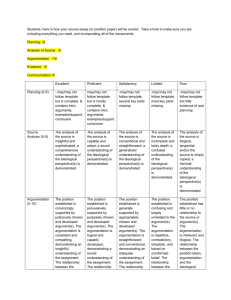

Argumentative reasoning in peer groups; conceptual issues and epistemological underpinning Clas Olander, University of Gothenburg Background, aims and framework Argumentation in school science settings is a growing interest especially the value of argumentation for unpacking the nature of claims and warrants for knowledge (Kelly, 2007, p. 453). In argumentation it is possible for the learner to elaborate and coordinate both cognitive and epistemic goals (Erduran, Osborne & Simon, 2005). It is through argumentation reasoning and knowing become accessible, both to the learners themselves and to others and then it could enhance the possibilities to perform assessment for learning (Black, Harrison, Lee, Marshall, & Wiliam, 2003). The skill to choose from different explanations following a discussion is a discursive practice essential in building scientific knowledge according to Jiménez-Aleixandre & Pereiro-Muñoz (2002). Analysis of argumentation is often done in relation to socioscientific issues. However this study’s analysis is towards a specific content, the evolution of life on earth. It is a topic that could challenge our ontological views, as well as our understanding of evolution. Like other topics it depends on a number of conceptual issues and their epistemological underpinning. Students conceptions about evolution have been investigated thoroughly through individual writings and interviews (see for example Thomas, 2000). The aim in this study is to investigate conversations in peer group discussions with focus on argumentation patterns towards a substantive content issue; the origin of variation. The aim is to put students´ own wording in the foreground; what students´ perceive as important conceptual and epistemological issues. The specific research questions are: - What conceptual issues are articulated and made important by the students? - How do students justify and support their claims about the origin of variation? Methods and sample The empiric data is generated through a group discussion between seventeen-year old students attending the Natural science programme at a Swedish upper secondary school. They are taking part in a teaching-learning sequence about biological evolution. It is their third lesson, the previous two have dealt with genes, inheritance, cell division, mutations and the common descend of life. The context is an ordinary lesson with three group tasks that the students move between. At one station they are supposed to discuss an issue about the origin of variation and new traits (figure 1). In total it is 29 students divided in seven groups that are videotaped. The teacher asks them to discuss one alternative at the time and, if possible come to an agreement. When performing this group discussion the students went to another room, turned on the video camera, discussed, turned the camera of and went to the next task. During evolution living organisms have evolved a lot of different traits. The origin of this enormous variation is: s strive to develop Need of great variation in order to get balance in nature Figure1. Issues to discuss in peer groups. Student’s use of arguments are being analysed with the help of Toulmins´ argumentation pattern, TAP (Toulmin, 1958/2003), which is summarised below in figure 2. Data Claim Warrant Rebuttal Backing Figure 2. Toulmins´ Argumentation Pattern Students make claims that are grounded in data; in this case the data is stated in the actual text (see figure 1) i.e. living organisms have evolved different traits. Students’ claims emanate from the alternatives in the assignment, which they are supposed to elaborate. Focus of the analysis is the various warrants that students use in order to support and justify their claims. Beside the three more or less mandatory elements (data, claim and warrant) in an argumentation there are also facultative components. Warrants could be supported by backings, which are assumptions that could be explicitly or implicit articulated. Rebuttals are limitations and boundaries where the claim may be valid or invalid. Findings Students’ utterances show a great variety of how they articulate and argue on different conceptual issues. The most frequently discussed issue is whether variation originates from individuals´ needs or from random changes in the gene pool. In order to exemplify the data and analysis (se next page) one short excerpt from a discussion between four students is shown below. In line 114 one student brings up a new example in the discussion; circumcision among Muslims. This is partly done as a reply to an earlier claim by student D that random change is unlikely, articulated as: … if it now is that it originated randomly how come that every animal on the bloody earth has succeeded adapting to its environment. 114 115 116 117 118 A: D: A: D: A: 119 D: 120 A: 121 D: 122 C: you know Muslims and such the boys /../ they cut this epidermis foreskin yes foreskin from the willie pip censor and they have done this as long as ever and their children they have the entire time got epidermis foreskin I mean and … it is nothing you need consequently it doesn’t develop at all … they don’t have to do this it has to do with religion even if they want to change they will … there will never be a change because it isn’t necessary they don’t need it in order to survive it is the same thing as ... it is evident that Michel Jackson’s kid will be Negro /../ his genes doesn’t change just because he himself gets white data claim … not the individual’s need of the trait. Expressed in line 120: even if they want to change they will … there will never be a change Living organisms have evolved a lot of traits ... the origin of this is … since warrant 1 (from A) 118: they have done this as long as ever and their children have the entire time got epidermis foreskin I mean warrant 2 (from C) 122: it is evident that Michel Jackson’s kid will be Negro /…/ his genes don’t change just because he himself gets white In between these utterances above student D put forward two counter arguments. First in line 119: and … it is nothing you need consequently it doesn’t develop at all /.../ because it isn’t necessary they don’t need it in order to survive and then in line 121: … they don’t have to do this it has to do with religion. Conclusion and implications The argumentation that student D put forward is an attempt to give more arguments that support the need-rationale, which has strong potential as an explanation among students (Southerland, Abrams, Cummins & Anselmo, 2001). When warrants are scrutinised Toulmins´ element backing could be applied. Although it has to be used with caution, since it often involves interpretation of implicit assumptions. In this case the utterance in line 119 … they don’t need it in order to survive could be seen as drawing on a connection between need and survival; only the needs that are essential for survival are important. Making this remark student D also states a rebuttal, as he points at limitations of where need is applicable. Furthermore it seems that student D rejects the circumcision example because it has to do with religion, meaning cultural evolution and not biological. The argument interposed by C, in turn 122 … his genes don’t change just because he himself gets white is a kind of helping argument. The interpretation of this remark is that it draws on a refusal of the notion that “acquired traits are inherited”. Since this idea is common among students (Jensen & Finley, 1995), the actively articulated refusal is an important utterance. Many of the disagreements could be traced to whether putting randomness or need in the foreground when explaining the origin of variation. Partly this is inherent in how the theory of evolution is understood; as one single process or two different processes. For instance it is possible that student D perceives that randomness is the one and only process that is involved in evolution. This insight could be used by the teacher in her/his assessment for learning, e.g. dividing the explanation in one part that is random, the origin of variation and one part that is not random, the selection part. Students own wording is accurate most of the time, for example the utterance which settles one group’s arguing on the issue randomness/need … random changes have occurred, just as it says, but they remained because they were needed. Students’ utterances are potential tools for teachers’ own “argumentation” that may have more impact i.e. a language that would touch and influence students more directly without devaluating the scientific clarity and stringency. Bibliography Black, P., Harrison, C., Lee, C., Marshall, B & Wiliam, D. (2003). Assessment for Learning – putting it into practice. Open University Press Erduran, S., Osborne, J &. Simon, S. (2005). The role of Argumentation in Developing Scientific Literacy. In K. Boersma, M. Goedhart, O. de Jong & H. Eijkelhof (Eds.), Research and the quality of science education (pp. 381- 394). Dordrecht: Springer. Jensen, M.S. & Finley, F.N. (1995). Teaching evolution using historical arguments in a conceptual change strategy. Science Education, 79, 147-166. Jiménez-Aleixandre, M.P. & Pereiro-Muñoz , C.(2002). Knowledge producers or knowledge consumers? Argumentation and decision making about environmental management. International Journal of Science Education, 24 (11), 1171-1190. Kelly, G. (2007). Discourse in Science Classrooms. In Abell,S & Lederman, N. (Eds) Handbook of research on Science Education (pp. 443 - 469). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, New Jersey/London. Southerland, S., Abrams, E., Cummins, C & Anselmo, J. (2001). Understanding Students´ Explanations of Biological Phenomena: Conceptual Frameworks or P-Prims? Science Education, 85: 328-348. Thomas, J. (2000). Learning about Genes and Evolution through Formal and Informal Education. Studies in Science Education, 35 (2000), 59 – 92. Toulmin, S. (1958, 2003). The Uses of Argument. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.