The Keren and the Shofar

advertisement

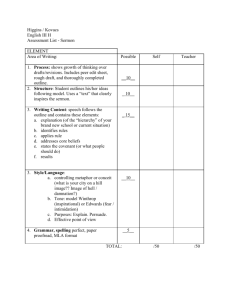

Bar-Ilan University Parshat Hashavua Study Center Rosh Hashanah 5774/September 25-26, 2014 This series of faculty lectures on the weekly Parsha is made possible by the Department of Basic Jewish Studies, the Paul and Helene Shulman Basic Jewish Studies Center, the Office of the Campus Rabbi, Bar-Ilan University's International Center for Jewish Identity and the Computer Center Staff at Bar-Ilan University. For inquiries, please contact Avi Woolf at: opdycke1861@yahoo.com. 1033 The Keren and the Shofar By Shalem Yahalom* In Tractate Rosh ha-Shanah 3.2, the Mishnah invalidates using a bone taken from the head of a bull for blowing the shofar: "All kinds of shofar are valid except that of a cow because this is a horn [= keren]." This assertion rests on the distinction between a keren - rendered here as horn - and a shofar. The tosafists and Nahmanides endeavored to understand the significance of this distinction. The tosafists were inclined to view it merely as a linguistic matter: those animal bones that Scripture refers to as a keren may not be used for the commandment of blowing the shofar. Only if the scriptural verse defines the bone as a shofar, is it fit for blowing on Rosh haShanah. This claim elicited detailed discussion of the ostensibly contradictory sense of verses mentioning both keren and shofar. In opposition to the scriptural linguistic approach, Nahmanides maintained in a sermon delivered in Acre towards the end of the 1270's that the distinction between a keren and a shofar stems from a fundamental physiological * Dr. Shalem Yahalom teaches at the Center for Basic Jewish Studies, Bar Ilan University. 1 difference.1 A bone that is constructed as a single unit is called a keren, and one with twopart tubular construction is a shofar. The inner part of the bone is called the male component and the outer part, the female component; to fulfill the commandment of blowing the shofar, only the female component must be used: The tosafists2 challenged…we might also say that [the horn] of a goat [gedi] is not valid, for it says in Scriputre, "The goat [tzafir]3 had a conspicuous horn [keren] on its forehead" (Dan. 8:5); however it must be said that a goat is also called a seh in Scriptures, as in "the sheep and the goat [seh kesavim ve-seh `izim]" (Deut. 14:4), and [the horn] of a sheep is a shofar, as it is written, "ram's horns [shofrot ha-yovlim]"4 (Josh. 6:4). All this follows the method of the commentators on this mishnah, but with all due respect I say that a shofar is none other than a hollow horn that has a male component inside and a crusted layer that can be peeled away from the male component, as those of sheep, goats, and ibex; but the horns of most animals that are of one bone are not called shofar in the holy tongue, 1 The tosafists and Nahmanides have a similar difference of opinion with respect to the distinction between dirt, or `afar, with which blood is covered after slaughtering, and ashes, or efer, which is not acceptable for performing this commandment. The tosafists established two criteria for `afar: a substance in which plants can grow, and an argument based on scriptural verses: "Here is a reference to ashes of trees (efer) in which plants can be grown; and even though it is not called `afar, it is used for covering…but whatever is called `afar, even though it does not produce growth, may be used for covering…for it is written, 'it contains gold dust (`afrot zahav)'…Since gold dust…does not produce growth, therefore the verse explicitly states that it is called `afar" (Tosefot, Beitzah 8a, s.v. hakhi). At the beginning of his remarks Nahmanides rejected the linguistic distinction, but further on reiterated the tosafists' position: "Should you say [it is permissible] since it is called `afar,…[we have the counter-example of] the dirt of the desert itself, which is pure dirt (`afar) and is not used to cover [blood] since plants do not grow in it…accordingly…anything in which plants grow can be used to cover…But here we see that pure dirt and all that is thus called, such as efer [=ashes] and gold dust can be used to cover, even though plants do not grow in it" (Nahmanides, Hullin 88b, s.v. Amar Rabba, מערבאed., Jerusalem 1996, p. 102). 2 The passage from the tosafists that he quoted in his New Year's sermon is no longer extant. 3 Tzafir is the same as se`ir (he-goat). A yearling is referred to either as an `ez or se`ir izim, or gedi. From the second until the end of the third year it is called a se`ir or se`irah. 4 Yovlim are the same as elim, and an ayil (sing. of elim) is an adult male sheep. 2 rather keren (Sermon for the Jewish New Year, M. L. Katznellenbogen ed., Jerusalem 1987, pp. 122-124). The quotes from Nahmanides' sermon presented thus far have been taken with slight changes from Hiddushei ha-Ramban le-Rosh ha-Shanah.5 What makes his sermon special, however, comes further on, where he introduces a personal note: I suggested this innovative view in my younger years, and ran it before the rabbis of France, Rabbi Moshe b. Rabbi Schneur, his brother Rabbi Samuel, and Rabbi Yehiel in Paris, through my relative Rabbi Jonah, who was studying there. They all arose and said: He has had his word, and he will be held accountable for it (p. 125). Mentioning these rabbis in his sermon was not just bibliographical happenstance. Around the year 1260 Rabbi Yehiel of Paris set out with a group of immigrants to the land of Israel, but did not manage to complete his journey; however his son and disciples settled in Acre. There these rabbis founded an academy called Beit ha-Midrash de-Paris, and through their presence there they strengthened French hegemony.6 For Nahmanides to deliver a sermon to them was like closing a circle. In his later years, when he took up residence in Acre, Nahmanides reiterated before Rabbi Yehiel's disciples the innovative view he had sent their master in his youth. As a novice disciple, Nahmanides had sought to submit his innovative idea to Rabbi Yehiel for his critique. Now he saw himself as having sufficient authority to challenge the words of the great tosafists.7 The polemical leaning of his sermon finds expression, among other things, in his style. When he wrote down his innovative ideas, Nahmanides' style had been tentative: "It seems to me" (p. 50). In his sermon, his tone was assertive: "With all due 5 M. L. Katznellenbogen, ed., Jerusalem 1987, pp. 50-52. 6 J. Prawer, Toledot ha-Yehudim be-Mamlekhet ha-Tzalbanim, Jerusalem 2001, pp. 159-163, 226-227, 247, 265-268, 272-271. 7 Often sermons delivered aloud document landmarks in the intellectual development of ethics. See M. Saperstein, Jewish Preaching: 1200-1800, An Anthology, Yale University Press 1989, p. 85. H. Pedayah notes things that Nahmanides and Rabbi Yehiel had in common. Both participated in JewishChristian disputations that were documented by both sides. In the wake of the disputations they each left the country in which they had been residing in order to move to the land of Israel, and Nahmanides chose to settle alongside Rabbi Yehiel's disciples. See H. Pedayah, Ha-Ramban: Hit`alut Zeman Mahzori ve-Text Kadosh, Tel Aviv 2003, p. 94. 3 respect to them, I say" (p. 124); "…this interpretation is true and sound and elegant, regardless of who might challenge it or who might concur" (p. 137). The controversy appears not to have been incidental, but rather to have stemmed from essential differences in world view between the tosafists and Nahmanides.8 The rabbis of France considered that the source of knowledge was revelation from the past, and therefore sought the distinction between a keren and a shofar in hints found between the lines of verses from the Torah. In 13th century Catalonia, however, people began to rely on factual findings from experimentation and observation, and by the early 14th century quasi-empirical explanations for natural phenomena had become characteristic of scientific thinking.9 The latter half of the 13th century also saw a rise in the influence of Thomism, which attempted to harmonize between faith and intellect rather than give supremacy to a single truth.10 Hence Nahmanides' search for a physical finding that would clarify the laws of the Torah should be seen as characteristic of the new scientific approach of his time and place.11 Perhaps the willingness to contend with objective data and not rely on homilies and hearsay is hinted at in the Sages' remarks on the straight shofar: "The shofar of the New Year was a straight one of antelope's horn…On the New Year, the more straightly a person directs his mind, the better" (Rosh ha-Shanah 26b). Translated by Rachel Rowen 8 On Nahmanides' way of presenting a new approach that obviates the need for arguments and explanations given by the tosafists, see I. Ta-Shma, Ha-Sifrut ha-Parshanit la-Talmud be-Eropa u-viTzfon Africa: Korot, Ishim ve-Shitot, Jerusalem 1999-2000, Part II, pp. 46-47. 9 L. Thorndike, A History of Magic and Experimental Sciences III, Columbia 1934, pp. 386-397; Zh. Leh- Gof, Yemei ha-Beinayim be-Si'am, Tel Aviv 1993, p. 209. 10 B. Netanyahu, Don Isaac Abarbanel: Medina'I ve-Hogeh De`ot, Jerusalem and Tel Aviv 2005, pp. 117-118. Roger Bacon shifted the emphasis from traditional knowledge to empirical experimentation. See B. Clegg, The First Scientist: A Life of Roger Bacon, New York 2003, pp. 195-196, 199-206. 11 Often Nahmanides based his rulings on scientific findings. See S. Yahalom, Bein Girona le-Narvona: Avnei Binyan le-Yetzirat ha-Ramban, Jerusalem 2013, pp. 226-242. 4