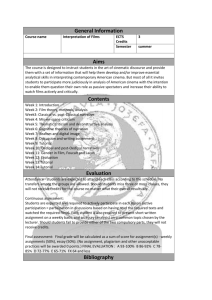

diasporic cinema: turkish-german filmmakers with

advertisement