A Town Unearthed

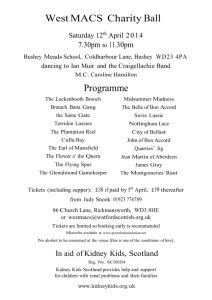

advertisement

Talk given by Thierry Biot – 15 November 2011 Quern Stones Thierry’s interest in Quern Stones began in June 2011 when he visited the site of the Folkestone Villa archaeological dig. On his visit he found that many quern stones had been excavated and found littered around the site. Following up this interest Thierry has researched the early history of quern stones and provided the research group with a fascinating talk about their development and importance as an early industry for Folkestone. Geologically the physical setting of Folkestone is characterised by lying at the eastern end of the Lower Greensand which comprises a group of Greensand beds forming an area known as the Chart Hills. Hythe Beds, Sandgate Beds and Folkestone Beds comprise an area of Greensands which are likely to have provided a rich natural source of material for working into quern stones. Indeed most quern stones found in the Folkestone area are made of Greensand. The Greensand Ridge stretches across Kent from Folkestone to Maidstone and Sevenoaks. The first grinding activity using stones is thought to be 40,000 years ago. At this time a simple flat stone called a quern which was used with a simple rubbing stone hand-stone in the Neolithic period. These early querns are known as Saddle Querns and were used in a rubbing motion backwards and forwards to work the grain. There is considerable debate concerning the dating of the onset of agriculture and settled activity but it is generally accepted that this was becoming an accepted lifestyle from 8,000 BC. The design of early quern stones changed very little during the Palaeolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic and even the Bronze Age, therefore in the period of transition from a nomadic to a settled lifestyle people continued to use the Saddle Quern. It is estimated that this design yielded 3-4kg per hour. About 500 BC many new designs of quern were developed. The most significant being the Rotary Quern. It is likely that a household would have had several types of quern which were used for grinding different types of grain and spices. It has been recorded that in addition to grain, querns were used for grinding nuts, seeds, herbs, spices, temper and iron. Rotary querns were used in a circular motion to grind material, meaning that the lower quern and the hand-stone (known as a Caitillus) were circular. The upper stone is kept in position by means of a spindle fixed in the lower stone and passing right through the upper stone and a handle/cleaver was fixed to the upper stone to rotate the quern. The grinded material fell to the sides between the two stones. The yield was 2-9 times better and the Rotary quern developed rapidly. However the Caitillus would wear down very rapidly and a stone of 5-6 inches would have worn down by half with its size within one year, and so most querns needed to be replaced within two years. Clearly this meant that grain would have been contaminated with ground stone and this is evident in the skeleton evidenced of this period which shows worn down teeth and dental damage. It is estimated that up to 2% of sand ended up in the grain. A quern survey was conducted in Kent in 1966 by W.S. Penn who built on the earlier work of E.C. Curwen in 1937. Changes in the design of quern stones from the Pre-Roman through the Roman period have been identified which reveal interesting facts about the design of querns. In the PreRoman period (100BC) the angle of the grinding surface was circa. 20 degrees, in the Early Roman the angle was circa. 15 degrees, in the Later Roman the angle was 10 degrees, and in the Late Roman the angle was 3 degrees or less. Greensand stones are noted for their quality and strength, and this is critical for grinding power and mechanical resistance to wear and tear. This means that Folkestone querns made from Greensand would have been very robust. Greensand was laid down in the Cretaceous period and there is local variation in the quality of Greensand depending upon whether it came from the Folkestone, Sandgate or Hythe beds. There was much discussion about the origin of the Greensand worked at the Folkestone Villa site which has not been identified as coming from the Folkestone beds. Querns have been found above and below the foreshore. Since Winbolt’s 1924 dig 20 quern stones have been found above East Wear Bay foreshore. In 1988 five querns were recovered from the cliff edge. During the dig between July and September 1989 a number of querns stones were recovered. In 2010 -2011 more stone have been found in the villa courtyard. From the foreshore itself between 1974 and 1990 over 30 quern stones both upper and lower stones have been recovered. The majority of these have been unfinished stones. There is considerable debate here as to whether the stone is local to Folkestone or brought from other beds of Greensand to be worked up in Folkestone. Is this evidence of early industrial production? Could it be that the stones were really worked up on the upper level and then dropped down to the foreshore due to a process of cliff erosion. Keller identified stones by sample type, and archived geological samples and this work needs to be followed up. Why were the stones just below the cliff and were they there is Roman times? Early quern stones found in Folkestone probably date from 100BC to 100AD. This is likely to be before the construction of the second villa. There has been much speculation regarding what the Folkestone querns were for. What were they used for grinding? One hypothesis is that they were used for grinding rock salt. This also raises questions about trade and where the querns went to once they had been worked up? It is very tempting to speculate on coastal sea trade as well as inland coastal trade via navigable rivers. Greensand has been identified in France where the beds continue across the channel. However, no quarry has been found there. It is more likely that quern stones were exported there, possibly via the trading route of Portus Itus. However, the process of silting up in northern France replicated the experience of Kent and trade routes ceased to be navigable. This silting up process begun in the early Middle Ages, and was contemporaneous to the process which took place in Thanet which resulted in the silting up of the Wantsum Channel. Greensand quern stones have been found in many Kentish locations. Some of these have been PreRoman and were recovered in the digging of the Channel tunnel in 2006. They have also been found at Thurnham Villa, Westhawk Farm, Ashford, Lede Cottages, Eastwood, Fawkham, Hayes Manor, and West Wickham. It is speculated that these may all have links with the Folkestone industry. One type of quern stone can be identified as the ‘Folkestone type’. Many questions have been raised – were the stones made for export or for the local market? Where was the local settlement at this time and who lived here? How long did it take to work up a finished quern? How many were broken in the process? Petrology will help us to discover and confirm the geographical location and provenance of the Greensand. Kate Holtham-Oakley added her knowledge of quern stones to Theiry’s research. We also learnt that 44 quern stone fragments have been recovered from the villa site since 2010. Some have been left in situ. Part of a German lava stone quern has also been found. In the 2011 dig season 61 quern stones have been found this year. But we know that many more stones exist as less than a 20th of the site has been excavated, therefore the recovered querns are a small sample of what is actually there. This season a Saddle quern has been uncovered in three fragments. Worked like a pestle and mortar it is likely to be early Iron Age and was made from Greensand. A very stimulating discussion raised many questions for which answers are needed if we are to understand the provenance of Folkestone’s Greensand, how Folkestone’s quern stone industry operated, and what impact it had on local and possible export trade