Estonian folklore. Taive Särg Historical periods of Estonian folk

advertisement

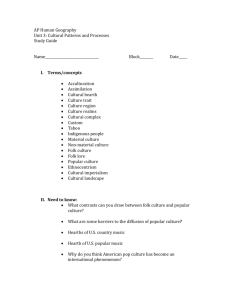

Estonian folklore. Taive Särg Historical periods of Estonian folk culture 1) Estonia was settled near the end of the last glacial era, beginning from around 8500 BC. Before German invasions in the 13th century proto-Estonians, with Finno-Ugric roots (or influence), worshipped the spirits of nature. Hunters-gatherers become gradually farmers ~1000-2000 BC. 2) 13th century German conquest brought along the Catholic faith, a class society, and an urban culture. Estonia was occupied in 1227. Despite numerous influences, Estonians kept their traditional ways of living and the old ways of thinking for a long time. 3) The Reformation took place in North Estonia 1523, Southern Estonia 1625. An Estonian language liturgy provided the background against which Estonian language printing and Estonian schools could emerge. Literacy started spreading among the people. These factors contributed to the gradual disintegration of the old oral and musical traditions and to the formation of new beliefs. These processes were gradual and the changes became firmly rooted only at the end of the 18th century. 4) Radical changes in the folk culture occurred during the second half of the 19th century and were connected with abolishing of serfdom (1816-1819) and buying land for freeholds in the 1860s. Increasing numbers of peasants moved to towns in order to study or work. The Estonian peasant society with its ancient traditions was becoming more and more modern. Being farm owners gave people a feeling of security and was a boost to their self-esteem. In the history of Estonian folk culture, the mutual influence of high and popular cultures have to be pointed out. The mediators here were the church and monasteries and also manor houses and towns. Language and identity According to the most popular theory Estonian language belongs to the Finno-Ugric language family, to the group of Balto-Finnic languages (läänemeresoome keeled). But several hypotheses about the development of the Estonian language during the earliest period of development up to the 13th century are now also considered to be of dubious reliability. It is unanimously agreed that ancient Estonian was influenced by various Germanic, Baltic and ancient Slavonic languages. This is proved by multiple loan words and several shifts in pronunciation. Estonia is geographically situated in Europe, but Europe is also a cultural term, representing some treats that are regarded as European in Estonia. In cultural terms Estonians have felt themselves sometimes as being Europeans, sometimes as being in opposition with Europe. The reasons for this opposition: 1) The Estonian language and culture have Finno-Ugric roots, but most European nations have Indo-European roots and languages. 2) For a long time (1227-1918, 1940-1991) Estonia was the colony of different European and European/Asian empires: Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Russia. Estonians have been identified themselves both as Europeans and as Finno-Ugric peoples. Estonia has stood on the cultural dividing line between Eastern and Western 1 Europe for for millennia. The Estonian cultural scene can be characterised by a multitude of peculiarities, the origins of which date back to the very distant past. In order to understand Estonian folk culture, it has to be recognised that this is a highly complicated and multilayered way of existence of a small nation who used to belong to the lower social status in its own country. An Estonian’s spiritual world was contradictory as well. It contained Christian and pagan characters, and it was necessary to get on well with both. Local areal cultures in Estonia There are also differences of local areal cultures in Estonia. The most noticeable differences exist between Northern Estonia Põhja-Eesti and Southern Estonia LõunaEesti. Their cultural differences and dialects date back to prehistoric times. Northern Estonia has more similarities with Finnish and Votian culture. Very special area of Northern culture are islands (Saaremaa, Hiiumaa, Kihnu) in Western Estonia. Estonian literary language bases on North and Central Estonian dialects. Besides large and culturally fairly homogeneous areas there are a number of small regions with a very specific character of their own. The most distinctive region is Setumaa which is located in southeastern Estonia and was separated from the rest of Estonia for long periods of time, thus developing a culture of their own with strong Russian influences; this culture has to a certain extent survived up to today. Setomaa has been incorporated to Estonia in 1920, earlier is has been belonged to Russia. However, despite the regional differences, there existed also the unifying features of the ancient Estonian folk culture that were common to the entire country. ‘ Tangible and intangible heritage Traditional cultural expressions include tangible and intangible heritage (folk art and folklore), the physical environment and the way of life. Disciplines that study folk cultural heritage are folklore studies folkloristika and ethnology etnoloogia. Aesthetic and pragmatic aspects exist together in folk life. In the Nordic countries, as in Britain and North America, immaterial and material folk culture are not separated as autonomous disciplines. But in Estonia and Finnish scholarly tradition material culture belongs to the realm of ethnology (etnoloogia). There exists the close linkage between folklore studies, ethnology and cultural anthropology. pärimus (*pär + i + mus) traditional cultural expression pärima be heir to, inherit; pärandama hand down; pärandus inheritance Folklore folkloor, rahvaluule folklore (= rahvas folk + luule poetry, lore) vaimne pärimus intangible cultural heritage = folklore (in Estonian and Finnish scholarly tradition) vaimne mental, immaterial < vaim spirit, mind, mental power Folklore (intangible cultural heritage) includes oral traditions, performing arts, social practices, rituals, festive events, knowledge and practices concerning nature and the 2 universe or the knowledge and skills to produce traditional crafts, “savoir faire” (‘know how’) folk beliefs rahvausk – common beliefs that are widely accepted as truth by most members of the group, e.g. old myths about world creation, supernatural beings, but also contemporary superstitions etc. Often beliefs appear in verbal form (proverbs, narratives), they are the bases of customs and rituals, can govern cultural practices. customs kombed – family traditions, calendar traditions, etc, often combining entertainment and magic verbal arts sõnalooming – folk songs (lyrics), folk narratives, short forms of folklore music and dances muusika ja tantsud folk music and dance rahvamuusika ja -tants – folk song melodies, instrumental pieces, folk dances, games with songs and music Folk art includes material objects aineline pärimus, rahvakunst – tangible cultural heritage aineline material, tangible < aine substance rahvariided traditional costumes – clothes, shoes, adornments elutarbed necessaries – implements, tools, furnishing, utensils, vehicles rahvustoit national dish – food, drink ehitised farm architecture – building materials, the types of settlement, farm buildings (barn-dwelling, granary, saun) rahvapillid folk music instruments special instruments – magic tools, toys, calendars kaunistused decorations, adornments Folklore Folklore, both ancient and new, forms intrinsic part of our human existence, like the air we breathe or the nature to which we belong. Matti Kuusi. Perhaps the most deeply Estonian are the age-old songs called regilaul that are closely related to Finnish folk songs, called runo song or kalevala meter songs. Estonians tend to view folklore as wondorous and admirable. These feelings stem largely from the Romantic age when folklore – particularly the songs – offered Estonians a means of viewing themselves and their culture as equal to the great civlizations of classical anitquity and medieval Europe. Important model for Estonians how to use folklore for developing national culture was Finnish culture and especially their great national epic Kalevala. Through the phenomenal success of the Kalevala folklore and folkloristics played a central role in the country’s eventual attainment of indepence. Even today, the standard name for folklore in Estonia is literally “folk poetry” – rahvaluule. This reflects the early and singular prominence of folk songs in Estonian intellectual life. Very similarly, the standard name for folklore studies in Finland is folk poetry studies kansanrunoudentutkimus. This feeling of wonder has its ill effects as well, however. It becomes easy to think of folklore as a thing of the past. Even worse, it becomes difficult to imagine that people create and use it today. Folklore becomes equated with the preindustrial community of old, the village or farm life so unfamiliar to many in the highly urbanized , industrialized Estonia of today. Images of murmuring epic singers or impoverished 3 peasant women in colorful folk costume seem remote and unimportant to modern experience. This Romantic heritage of folkloristic studies prepares us to think of folklore in idealistic terms – as the shining, precious and beautiful products of ordinary life. Folklore is more than simply curious relics of the past. It is a dynamic and everpresent dimension of human experience everywhere in the world. Folklore flourishes even amid te neweast and most technologically advanced circles of human acitvity (e.g. the xerox and fax machines, the computers, newspapres). Folklore reflects human creativity and traditionality in all occasions, including everyday life. It reflects the mentality of the group and changes in the course historical and cultural developments. Folklore is transmitted in different situations and by different means, including oral tradition, media and internet. Folklore includes aspects of agression and negative behavior as well. There are verbal obscenities, cruel nicknames, pejorative labels, derisive satire and parody etc. – all these cultural expressions also belong to the human interaction. Professional, institutionalized arts and religions are not folklore. Folklore has 3 basic components: group (~folk), text (~lore), context. 1) Group (~folk). In classical (old) folkloristics the subject of folklore was country folk. Today researchers define “folk” of folklore as any and all people who, through participation in small groups, communities or networks, exert influence upon one another and create their own shifting and unofficial cultures. Groups may be longstanding or ephemeral, and nearly everyone belongs to multiple groups at the same time. “Folk” of this sort can be found as easily in preagrarian hunter-gatherer societies as in the contemporary urban metropolis. 2) Text, tradition (~lore). Likewise “lore” should be understood in their broadest sense – as ever-changing expressions of cultural community and continuity. 3) Context – the performing situation. In wider meaning the cultural, social and historical background. 4