REGULATION OF GMO CROPS AND FOODS: KENYA CASE STUDY

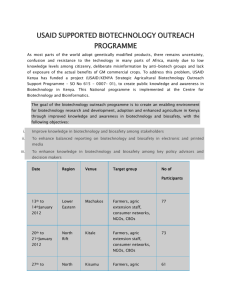

advertisement