Background Document by William Maloney of the World Bank

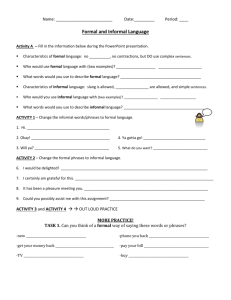

advertisement