Barbora Charvátová

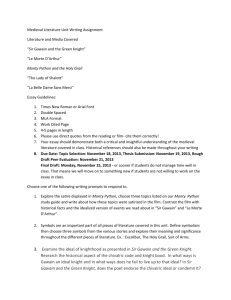

advertisement