Ethical theories

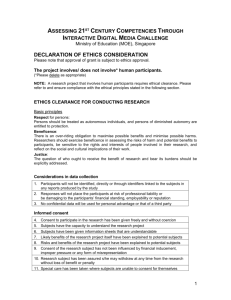

advertisement