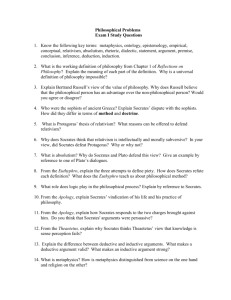

21 - The Open University

advertisement