CELESTIAL PHENOMENA: COLIN McCAHON

advertisement

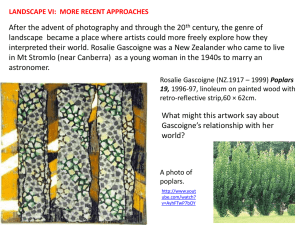

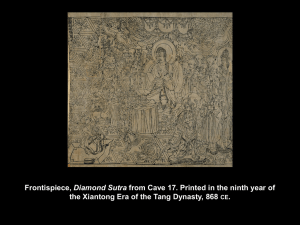

CELESTIAL PHENOMENA: COLIN McCAHON JAN M. WHITE University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland 1020, NEW ZEALAND. Funded by a grant from the University of Auckland. ABSTRACT. This paper will examine a selection of works by the New Zealand painter Colin McCahon (19191987), in which astronomical phenomena such as the comet and the star are used symbolically. Metaphorical symbols and emblems such as these form part of a visual ‘language’ used by Western artists to cross over between outer reality and inner subjective experience.1 To facilitate this process of interpreting experience McCahon used symbols as ‘transitional objects’2 enabling him to speak about such personal issues as his own existential crisis, to question cultural values and through which aspects of identity are indicated.3 McCahon’s sources and influences will be touched upon to reveal underlying issues of identity and of existential crisis on both an individual and a collective, cultural level. Western iconography has its roots in antiquity. By the fourth century of the Christian era the Egyptian scholar Horapollo Niliacus had compiled approximately two hundred symbols and emblems for his text Hieroglyphica.4 This catalogue was republished in the sixteenth century in various translations and illustrated by artists such as Albrect Dürer. Its publication encouraged many Northern artists including Dürer, Albrect Altdorfer, Mathias Grunewald and Hieronymus Bosch together with contemporaneous Italian artists such as Giovanni Bellini, Giogione and Titian to create from its pages an expanded visual ‘language’ of symbols. Horapollo’s Hieroglyphica thus became a source for developments in the use of astronomical and natural phenomena during the sixteenth century. 5 In antiquity phenomena such as comet and star sightings or meteorite and lightning strikes were interpreted as omens of good or evil. These signs where believed to be portents signalled by mythological gods and goddesses indicating the outcome of important events such as wars and the birth or death of great leaders. Ancient Akkadian and Babylonian Cuneiform for instance used the star to signify ‘god’ when placed before a name. Later pagan Imperial Roman iconography used the star for example to symbolise the astral existence of the Discouri, Roman emperors and heroes.6 These notions were absorbed into Biblical texts such as Revelations and used in religious imagery. 1 Winnicott,D. The Maturation Processes and the Facilitating Environment. 1965. Hogarth Press,London. Ibid. 3 Summers, J. ‘To Hell With Culture.’ New Zealand Monthly Review Number 28. October 1962 ‘In his painting particularly, [McCahon] questioned, saw through and attacked the cultural framework; a thing that can never be more than provisional anyway, because man’s spirit is always larger than it…’ 19 4 Horapollo,N.,Trans. Boas, G. The Hieroglyphics of Horapollo. 1993, Princeton University Press. New Jersey. 5 For more on this see Grabar, A. Christian Iconography:A study of its origins.1969, Routledge and Kegan Paul, London. 6 Ibid. 132. 2 Comets and stars have long been considered to be portents of birth or death in Western culture, as is recorded in literature and the arts.7 A possible candidate for the bright star heralding Christ’s birth was thought to be the appearance of Halley’s comet in 12 BC used for instance by the early Renaissance Italian painter Giotto di Bondone in his Adoration of the Magi (1303-06). This comet either marks the birth of Christ or is perhaps an omen of the infant’s future death on the Cross. Giotto’s is believed to represent the reappearance of Halley’s comet in 1301.8 9 McCahon studied and admired early Italian painters such as Giotto, Bellini, Giorgione and Titian as well as Northern sixteenth century artists such as Dürer, Grunewald and Altdorfer, uplifting emblems and symbols from their work for his own painting. Although McCahon’s work shows stylistic changes over the decades death and existential crisis were subjects he addressed from the outset of his career as a painter. Sometimes he did this formally through symbols such as the comet, the star and the triangle as a means of reflecting on the nature of death or to question the purpose of life.10 He marked change or spiritual transformation as a ‘journey’ through emblematic landscapes in works like Six Days and Nights in Nelson and Canterbury (1950), and the Northland Panels (1958). These series of barren landscapes represent Christ’s ‘journey’ through the Stations of the Cross underlining McCahon’s identification with the ‘artist-prophet’ figure. This set of symbols also represents the collective separation and isolation felt by the European diaspora to New Zealand for whom this ‘new’ country represented the ‘Promised Land’. 11 This dual personal and collective cultural reality is acknowledged in the writer John Summers’ comment that ‘naturally what McCahon found within himself he also found in society.’12 The identification of the artist with the prophet figure can be traced back to Marcilio Ficino (1433-1499), whose Neo-Platonist ideas impacted upon Christian thought. Ficino promoted the notion that all men who excelled in the arts were born under the influence of the star of genius and were melancholic by disposition. A disposition underlined by Dürer’s remark that ‘A boy who practices painting too much may be overcome by melancholy.’ 13 Dürer’s comment is applicable to McCahon’s life, as is evidenced by his dedication to being an artist often at the expense of his family and friends and by his increasingly dominant melancholic doubt and fear of death expressed through the symbolism in his work. 14 Dürer viewed his artistic role as a 7 Classical poets and writers such as Virgil (70-19BC), and Tacitus (?55-?120AD), tied the appearance of comets to the deaths of Roman emperors. Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare (1564-1616), in which it is noted that ‘when beggars die, there are no comets seen. The heavens themselves blaze forth the death of princes.’ William Shakespeare. Julius Caesar. 2:2. 8 Olsen,R ‘Giotto’s Portrait of Halley’s Comet.’ Scientific American 240. May 1979 160-70. 9 The well-documented life of the Biblical King Herod marks the planetary configuration of Jupiter and Saturn in 67BC as the more likely phenomenon recorded as the Star of Bethlehem. 10 In late works such as Through the Wall of Death, A Banner (1972), McCahon depicted the transitory nature of life as the play of light and shadow. 11 Chapman,R. ‘Fiction and the Social Pattern.’ Landfall 7 1953 26-58. Richardson,J. A Summer’s Excursion in New Zealand, with gleanings from other writers. Kerby and Sons. London 1954 p143. Chapman,T. Letters and Journal quoted from Thomas Chapman to Church Mission Society London 1830-1869. Shepard,P. English Reaction to New Zealand Landscape Before 1850. Sigma Print. Victoria University Wellington. 1969 30. Bell,C. ‘The Big ‘O.E.’: young New Zealand Travellers as Secular Pilgrims.’ Conference Paper 2000. Unpublished. 12 Summers 1962 20. 13 Dürer, A. Dürer’s papers. British Museum, London. Sloane 5230, fol.5. 14 Brown,G. Three Paintings by Colin McCahon. Websdale Printing Group, Sydney, 1998 25. ‘As a result of his passionate commitment to his art a schism exists within the family that calls into doubt his willingness to truly devote himself to their welfare. He sees the importance of the Christian message, but how does he apply it to his own situation ‘calling’ in service to God. He was one of the first artists to use self-portraits in works to create a political subtext. McCahon followed this model, also inserting his self-portrait into many of his compositions or using his self-image for the prophet Christ and for Saint Paul as exemplified in Crucifixion: Apple Branch (1950), which is understood to be McCahon, his wife Anne and his son William and I Paul (1946), thought to be a self portrait.15 McCahon’s painting Sacred to the Memory of Death (1955), combines the comet, the sun and triangles together with a dark rectangular symbol in the top left of the composition he used to represent the Entombment from the Passion Cycle. These symbols all refer to death and through death to the Resurrection with its implied promise of salvation. The sixteenth century Northern artists McCahon studied during his early years repeatedly used astronomical phenomena as exemplified in Altdorfer’s Berlin Nativity (1511), dominated by a huge golden nova with blue concentric circles. Another example is Dürer’s Melencolia I (1514), in which a comet sweeps across an ominous night sky. Dürer’s interest in astronomical phenomena followed Biblical texts such as Revelations and was further inspired by Neo-Platonist writings.16 He used stormy weather, lightning, solar and lunar eclipses, flaming stars and comets to underpin the message of the Passion Cycle, Biblical narratives and in secular works. On the verso of his Saint Jerome in the Wilderness (1494-98),17 for instance Dürer painted a large flaming red comet – perhaps as an expression of spiritual insight. Dürer’s and Altdorfer’s visions of the ‘heavens and the revelation of heavenly phenomena stand squarely in the transitional moment of early modern thought - on the threshold of modern science but still well within the inherited traditions of astrology…’18 Contemporaneous Germany was dominated by a belief in connections between the divine, heavenly realm and worldly life. This belief reinforced the notion that human events were reflected in nature and were influenced astrologically by astronomical phenomena. Ficino had positioned the melancholy nature of the Renaissance man of genius within the framework of Christian Neo-Platonic mysticism.19 This thinking is believed to have influenced Dürer and to be reflected in the content of his etching Melencolia I. In this work Dürer is thought to be referring to the melancholia imaginativa as described by Heinrich Cornelius ?’ McCahon,C. 1981 Exhibition flyer. A journey into the darker terrain of his nature was alluded to by McCahon who remarked that ‘sometimes I feel terribly sad, it hurts and it’s hard to work at all…I think I am a Christian – perhaps I am. I think I am a good guy – but I’m not.’ McCahon,C. McCahon papers. Hocken Library, Dunedin, New Zealand. The hostile reception with which the New Zealand critics and the public received McCahon’s work is illustrated in a letter from McCahon to Wystan Curnow on October 9th,1975 which reads ‘Thanks for your review in the Listener. It is the first and only serious comment I’ve had. There has been a deathly silence all round. You cheer me, I’ve been a bit sad about it, I thought I was saying something.’ This was thirty years after McCahon had begun to paint. 15 Brown quoted of Crucifixion: Apple Branch that ‘There is an understanding among surviving members of the McCahon family that the three personages in the painting represent McCahon himself, his wife Anne and his son William. Perhaps the fact that Anne and William occupy one landscape while McCahon is segregated in the other, indicates his acknowledgement that a conflict exists at the centre of his life. Three Paintings by Colin McCahon. Websdale Printing Group, Sydney, 1998 25. New Zealand painter Doris Lusk, who owned I Paul said that she ‘always used to imagine that in [this] striking early painting there was a quite haunting self portrait; a prophesy of the future, indeed the portrait of a prophet...Colin always had a particularly direct and arresting gaze, and this confronts one with forceful exaggeration in the eyes of I Paul set in the ascetic bearded face.’ Bulletin. Robert McDougall Art Gallery Number 52. 1987 3. 16 Dürer’s godfather, Anton Koberger, published Ficino’s letters in 1496. 17 For more on this see Carritt,D. ‘Dürer’s St. Jerome in the Wilderness.’ Burlington Magazine 99. 1957 363-66. 18 Silver, L. ‘Nature and Nature’s God: Landscape and Cosmos of Albrect Altdorfer’. The Art Bulletin. June 1999 196210. 19 Ficino,M. Libri de Vita Triplici. Florence, 1489. Agrippa of Nettersheim (1486-1534 or 35), in his text De Occulta Philosophia, also influenced by Ficino’s writings. In Melencolia I the symbolic cuboid shape Dürer placed to the right of the composition, a cube in perspective with its opposite corners cut off, represents order (perspective), and erudition (scholarly knowledge). The sunrise (or sunset), in the background is uplifted from the Passion Cycle imagery and used as a warning of danger or retribution. 20 The figure in Melencolia I is depicted as the ‘star-crossed’ muse with her astrological stars indicated by the magic numbers on the wall behind her and by the comet crossing a nocturnal sky. The star motif also refers to the creative capacity of the imagination which the Swiss physician and alchemist Paracelsus (1493-1541), a contemporary of Ficino and of Dürer, named ‘the inner star’. The notion of the artist as melancholic genius has long been a familiar one with the ‘star-crossed’ artist identified with by Western artists through the centuries. 21 Artists such as Paul Gauguin and Vincent Van Gogh are examples of individuals who lived the ‘star-crossed’ lives of the artist-genius – as was McCahon himself. The emblematic star, subject of McCahon’s Night Sky (1965), refers to this notion of the artist-genius by reiterating Van Gogh’s Starry Night (1888), and The Starry Night (1889). Writer Gordon Brown ties McCahon’s John in Canterbury (1959),22 to Van Gogh’s Crows Over the Cornfields (1890). The crows in Van Gogh’s work represent death. 23 McCahon refers to Van Gogh’s symbolism remarking that in his work John in Canterbury ‘the words are the crows.’ 24 McCahon’s texts are infrequently a despairing voice often contradicting the imagery and underpinned by an atmosphere of anxiety and separation, indicating his identification with the ‘outsider’, the unheard artist-prophet and reflecting the cultural crisis of identity suffered by the European diaspora. The use of the astronomical comet as an emblem marking death appeared in McCahon’s work in the early 1970s. In 1974 McCahon personalised the comet symbol in an exhibition titled Jumps and Comets: Related Events in my World.25 For example in Comet (Series F1-3 1974), comprising three panels and Comets (Series F4-7 1974), comprising four panels, for example, he uses the comet as a metaphor to mark the deaths of three of his friends and his mother between 1971 and 1972.26 This series comprises predominantly black canvasses with low horizon lines above which a tiny white comet arcs progressively upwards through the series of canvasses. Perhaps the stark emptiness of the composition expresses the void of existential crisis. The 1970s Comet series is related stylistically and through the imagery to McCahon’s Jump series. However, if the Comet series was about marking particular deaths then McCahon’s Jump series was about the act of dying. The abstracted landscape locates these works on the West Coast of Auckland, New Zealand. A wild, unpredictable coastline evoking a sense of danger through steep, precipitous cliffs and crashing seas. Transitional paintings, such as 20 See Silver. June 1999. And Roob,A. Alchemy and Mysticism. Taschen,Cologne. 1997. p203. The Surrealists favoured the star motif whose influence on McCahon’s works takes the form of the juxtaposition of image and text and contradictory elements between the imagery and text. 22 Brown notes that John in Canterbury was painted directly prior to McCahon approaching the Catholic Church in 1959. 23 Brown,G. Colin McCahon: Artist. Reed Publishing, Wellington. 1999 76-77. 24 McCahon,C. Colin McCahon: A Survey. Auckland City Art Gallery, Auckland. 1972 27. 25 In March of the previous year Lubos Kohoutek, a Czech astronomer working in Germany had discovered the comet Kohoutek. 26 Brasch,C, Editor of the literary magazine Landfall, mentor and patron to McCahon who died in 1971. Writer R.A.K.Mason died in 1971. McCahon’s mother died in 1971and James K.Baxter, poet and friend to McCahon died in 1972. 21 Jumps 25 (1973-74), combines comets and landscapes in a series of panels. Jump 28 (1974), traces the path of a leap from the Earth to the heavens – perhaps representing a leap of faith. Jump I/IV (1974), traces the path of these leaps as tiny dots together with three black columns symbolic of the Christian Trinity and numerals that reference the six days of Creation from Genesis.27 The white dots on a black canvas representing the comet are repeated in Am I Scared (1976), and Scared 3 (1976). This series expresses, through these symbols, a warning of the inevitability of death and the existential fear this provoked for McCahon. The symbolic dotted line begins to trace the form of a Tau Cross in I considered all the acts of oppression (1982), McCahon’s last work. The connection between death, the ‘journey’ through the landscape, representing Christ’s journey through the Stations of the Cross, and Salvation through the Trinity, is similarly expressed through the symbol of the triangle. Dürer used the triangle in works such as the Adoration of the Trinity (1511), as a device to accentuate the figure of Christ on the Cross and to symbolically refer to the Trinity. The deep blue of the gilt-edged cloak in the background accentuates the triangular form of the Tau Cross, which is further defined by a layer of soft, pale clouds along its sides. In this way Dürer refers to the perfection and harmony of divine geometry represented by Aristotle’s Golden Section. He ties this together with the triangle and the Trinity, through which Salvation is promised. McCahon’s fascination with death and fears around the gaining of salvation symbolised through the triangle are evidenced in his charcoal drawing A New Way of Dying (1969), in which he ties together the triangle and death. The text of this reads ‘If you can afford a psychiatrist, if you’re suffocating with plush, stuffed with money worries and responsibilities, try being poor, not that it will cure you but at least as a new way of dying you won’t find it lonely.’28 Beneath this hand-written text is a roughly drawn triangle along two sides of which the same text is rewritten. The Holy Name (1965), also underlines this connection between the triangle, the Trinity - in the division of the canvas into three sections and to salvation through death with the letters IHS, IHSUS. 29 In McCahon’s A Candle in a Dark Room (1943), the triangular pyramid may, through its triangular shape, represent the Christian Trinity. Altdorfer recorded an extraordinary example of the connection between the triangular symbol to mark a particular death in his illustration for Joseph Grünpeck’s Historia friderici et maximiliani,30 commissioned by Emperor Maximillian in 1508. This print documents a fall of stones of great weight that fell from the heavens on November 16th, 1492 in Alsace, France. In this fall was a huge triangular meteorite, still extant, weighing 127 kilograms.31 The event was reported in the 1493 Nuremberg Chronicle interpreting this fall of meteorites as an omen heralding the death of Emperor Frederick III, father of Maximillian. There is a parallel between this triangular shaped meteorite and the geometrical form used by Dürer in his Melencolia I. To the right of the figure in this etching the large triangular rock is believed to be symbolic of the arts and architecture, 32 reflecting the notion of the divine nature of geometry following Aristotle. The triangular pyramid in McCahon’s A Candle in a Dark Room may well refer to Dürer’s Melencolia I. McCahon’s triangular pyramid matches Dürer’s geometrical form with its cut corner on the left, also 27 McCahon exhibited these series of works together in a show at Barry Lett Gallery in 1974 (May-June), calling the show Jumps and Comets : Related Events in my World. 28 McCahon,C. McCahon papers. Hocken Library, Dunedin, New Zealand. IHS and IHSUS are the Greek for Jesus. Grünpeck,J. Historia friderici et maximilliani. Haus, Hof und Staatsarchiv, hs Böhm. 1508. Nr. 24, fig.12. 31 Amphoteric chondrite, LL6, Catalogue of Meteorites, Museum of Meteorology, University of Rome. 32 Roob. 1997 203. 29 30 missing behind the lettering of the text in McCahon’s painting. The pose of the muse in Melencolia I is based on Dürer’s Christ as Man of Sorrows (1493-94), symbolically eliding the notion of the melancholic genius and the artist as the Christ-like prophet figure. In McCahon’s work the candle, symbol for the artist/prophet, replaces Dürer’s figure, paraphrasing Christ’s epithet as ‘light of the world’. The sky behind the candle acts as a warning of Retribution or danger as it does in Dürer’s etching. The warning of Divine Retribution through the symbolic sunrise/sunset became the primary subject in McCahon’s Storm Warning (1980-81). Here nature’s threatening crimson sky becomes the central narrative, creating an atmosphere of anxiety, underlined by text and title. Perhaps Storm Warning was an omen for McCahon as the reappearance of Halley’s comet in 1985-86 heralded his pending death, which followed in 1987. In conclusion McCahon used symbols and emblems to mark passage between subjective and objective experience. He developed an abstracted ‘language’, which included astronomical phenomena such as the comet and the star that was based on Biblical symbolism from the Western cultural tradition. Drawing on Northern and Italian sixteenth century sources McCahon used this symbolism to examine the nature of death to explore the human condition and to question collective social values. In so doing he constructed a personal identity that reflected European cultural norms such as the artist as prophet figure. The triangle, the rectangle, emblematic landscapes and the play of light and shadow were also symbols that he uplifted and used to examine the nature of death and to express aspects of existential crisis. This symbolism reflects both McCahon’s own existential crisis and the cultural crisis of identity of the European diaspora to New Zealand, precipitated through separation and isolation from their cultural roots.