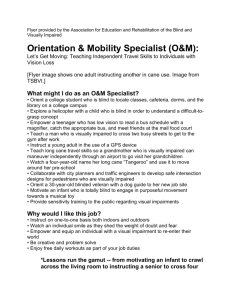

Preschool Children - Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired

advertisement