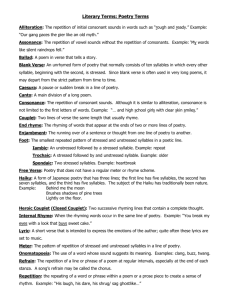

“hiss” “buzz” “whirr” “coo”

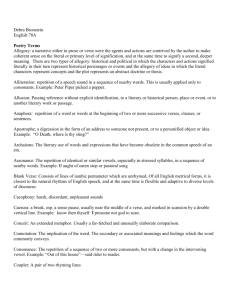

advertisement

Poetry Terms (pirated from Mrs. Eagles!) 1. Sound Effects Alliteration: The repetition of the same sound at the beginnings of words: “sessions of sweet silent thought” or “Apt alliteration’s artful aid” Onomatopeia: Words that by their sound suggest their meaning; the sound echoes the denotative sense: “hiss” “buzz” “whirr” “coo” Rhyme Scheme: The pattern of rhymes at the ends of lines, usually analyzed by assigned the same letter of the alphabet to each similar sound. The rhyme scheme for the English or Shakespearean sonnet is abab cdcd efef gg. 2. Rhythmic effects Enjambment: The continuation of a sentence from one line of a poem to the next (do not pause at the end of such a line as you read the poem). In this selection from Robert Frost’s “Mending Wall” the first line carries over to the second and the third carries over to the fourth— “Spring is the mischief in me, and I wonder If I could put a notion in his head: ‘Why do they make good neighbors? Isn’t it Where there are cows?’” In his poem “To a Poor Old Woman,” William Carlos Williams breaks down a sentence three times in order to present an old woman sensuously eating plums. The 1st and 4th lines are end-stopped, the middle 2 are enjambed. They taste good to her. They taste good to her. They taste good to her Foot: The basic unit of rhythm in verse, a foot is a group of stressed or unstressed syllables; as feet are repeated, they form a metrical pattern. “New York is home to cats and kings” (4 iambs) “Double, double, toil and trouble” (4 trochees) “Starting the car was a joy for the boy” (3 dactyls) “Underneath his broad smile grew a dangerous guile” (4 anapests) SPONDEE: 2 syllables—equally stressed as far as possible: “heartbeat” “childhood” “bookcase” “Hot sun, cool fire” IAMB: TROCHEE: DACTYL: ANAPEST: 2 syllables—unstressed, stressed: 2 syllables—stressed, unstressed: 3 syllables—stressed, unstressed, unstressed: 3 syllables—unstressed, unstressed, stressed: Meter: The regular, rhythmic pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables, measured in feet. one foot - monometer two feet - dimeter three feet - trimeter four feet - tetrameter five feet – pentameter six feet - hexameter seven feet – heptameter eight feet - octometer (the “alexandrine” is 6 iambs) Scansion: Dividing the poetic line into feet, then counting feet in order to determine meter. Because / I could / not stop / for death He kind– / ly stopped / for me iambic tetrameter iambic trimeter 3. Figurative Language (non-literal use of language) Apostrophe: Directly addressing someone absent or dead, or some abstract or imaginary quality or concept: “Death, be not proud ” “Rose, thou art sick” Connotation: The emotional implications and associations that words may carry, as distinguished from their denotative meanings. Compare: “dine” with “eat”; “admirably schooled” with “well trained”; “junkie” with “substance abuser” Denotation: The basic meaning of a word, independent of its emotional associations Imagery: A collective noun for “image.” Images are the visual content of poetry; they are representations in poetry of any sensory experience—pictures seen, sounds heard, sensations touched, tasted, smelled—which the poetic words evoke in the reader’s mind. “Poetry engages our capacity to make mental pictures.” (Edward Hirsch) Metaphor: Any comparison in which one thing described in terms of another: Walt Whitman characterized grass as “the beautiful uncut hair of graves.” Metonymy: The substitution of the name of an object closely associated with a word for the word itself. We say “The pen is mightier than the sword” and mean that writing (the pen) is more powerful than warfare (the sword). Metonymy employs concrete, tangible terms to convey abstract states. We say “the heart” when we mean “the emotions.” Overstatement (Hyperbole): Saying more than is literally meant, or than is literally true. Exaggeration. Overstatement may heighten effect or be humorous. Listen to Macbeth talk about how he can’t wash his hands of the blood of King Duncan, whom he has just murdered: (“incarnadine” means blood red; Shakespeare uses it as a verb here) “No; this my hand will rather The multitudinous seas incarnadine, Making the green one red. Understatement: Saying less than is meant or literally true; the literal sense of what is said falls detectably short of the magnitude of what is being talk about. Understatement is quite effective since the reader tends to fill in what is missing. From Thomas Hardy’s poem “The Man He Killed”: “Yes; quaint and curious war is!” Or, Artemus Ward’s humorous: “A man who holds his hand in a lighted fire will experience a sensation of excessive and disagreeable warmth.” Personification: Endowing animals, ideas, abstractions, inanimate objects with human qualities—human form, human personality, human intelligence and/or human emotion. Maya Angelou describes a powerful wind against her chimney: “The chimney made fearful sounds of protest as it was invaded by the urgent gusts.” Pun: A play on words based on the similarity of sound between two words with different meanings. Some common poetic puns involve “sun” and “son” or “I” and “eye.” Mack and Boynton cite a witty limerick: There was a young fellow named Hall, Who fell in the spring in the fall; ’Twould have been a sad thing If he’d died in the spring, But he didn’t—he died in the fall. Simile: Metaphoric comparison of two things using like or as in the statement. My love is like a red, red rose That’s newly sprung in June: My love is like the melodie That’s sweetly play’d in tune. Synecdoche: A type of metonymy, which substitutes the name of a part of something for the whole thing. We say “hired hand” when we mean a “worker. We say “wheels” for a car and “threads” for clothes. In both cases, an important part of the object (the threads or the wheels) stands for the whole. 4. Forms and Structures Blank Verse: Poetry written in unrhymed iambic pentameter, often used for longer dramatic and epic poems. Milton used blank verse in Paradise Lost and it was standard form for Elizabethan theatre. “It has been estimated that three-fourths of all English poetry is written in blank verse. (Hirsch) Couplet: Two consecutive rhyming lines of poetry. Shakespeare always ends his sonnets with a couplet, and often uses a couplet to signal the end of a scene that is in prose or blank verse. “The couplet has been an elemental stanzaic unit—a couple, a pairing—as long as there has been written rhyming poetry in English.” (Hirsch) Free Verse: (Literal translation of vers libre, employed by French poets seeking freedom from the rather cumbersome alexandrine). Free verse is unrhymed, nonmetrical—“a poetry of organic rhythms. . .often inspired by the cadence of spoken language.” (Hirsch) Quatrain: A stanza of four lines; often used as a unit of composition in longer poems, the quatrain may also be complete unto itself! “It is probably the most common stanzaic form in the world.” (Hirsch) Rhyme possibilities: abab aabb abba aaba abcb Sonnet: A poem almost invariably of fourteen lines, written in rhymed iambic pentameter (in English), and following one of several set rhyme schemes. The two basic sonnet types are the ITALIAN (PETRARCHAN) and the ENGLISH (SHAKESPEAREAN). The Italian sonnet is distinguished by its division into the octave (8 lines, rhyming abbaabba) and the sestet (6 lines, rhyming cdecde, cdcdcd, or cdedce) The English sonnet uses four divisions: 3 quatrains (each with a rhyme scheme of its own) and a couplet. The typical rhyme scheme is abab cdcd efef gg. The Spenserian sonnet complicates the Shakespearean form , interlinking rhymes among the quatrains: abab bcbc cdcd ee. Whole books have been written just on the sonnet form! 5. General Terms Allusion: An indirect reference to a biblical, literary, or historical person, place, or event—that which is alluded to is only implied, not directly stated. Othello, as he gazes on Desdemona in preparation to strangle her, says: “I know not where is that Promethean Heat / That can thy light relume.” In her short story “Parker’s Back,” Flannery O’Connor alludes to the story of Moses and the burning bush when Parker runs a tractor into a tree, the tree burns, and Parker is suddenly “changed.” Diction: The writer’s choices of particular words or expressions—choices intended to effect clear, effective, and precise meaning. In “Richard Cory,” poet E.A. Robinson describes a man who was “a gentleman from sole to crown.” The word crown (meaning his head) is also suggestive of royalty, and serves the “gentleman” description in a particularly effective way. Explication: Literally, an unfolding or spreading out. Explication is a method of uncovering meaning, line by line, of a written work. This close analysis calls attention to words, images, relationships, allusions, ambiguities— all the devices skillfully employed by the writer that together comprise art and meaning. Irony: The contrast between what is stated and what is meant (verbal), what a character knows and what the audience knows (dramatic), or what is expected to happen and what really happens (situational). Broadly, irony recognizes the “reality” that is separate from the “appearance.” When Huck Finn says “All right then, I’ll go to hell!” The reader knows that what Huck says and believes (he will go to hell) is different from what Mark Twain says and believes (Huck should be sainted for his compassion). In a popular country song, a sad farmer (who has crops to tend and four hungry children to feed) says to his wife who has abandoned him, “You picked a fine time to leave me, Lucille.” In this case, the farmer’s seeming words of praise of course really imply blame—it’s a terrible time to leave! Juxtaposition: A comparison achieved by placing two things or two concepts side by side in such a way as to imply that the reader or listener should look for a connection. The great virtue of juxtaposition is that it is unobtrusive. Paradox: “A paradox makes a single truth grow from two elements that literally contradict each other.” (Boynton and Mack). The Bible says “The last shall be first.” We hear that “less is more.” Richard Bentley asserted that there are “none so credulous as infidels.” Paradox is more than just witty; it invites the reader to understand “the tensions of error and truth simultaneously.” Merriam Webster’s Reader’s Handbook Symbol: Something that is itself and also stands for something else: the apple is a piece of fruit that represents temptation and fall; the dove is a graceful bird and also the symbol for peace. Poet Garcia Lorca said, “The form and fragrance of just one rose can be made to render an impression of eternity.” Tone: The emotional climate of the poem—usually complex. Tone is often defined as the speaker’s implied attitude toward the subject, himself, the audience, or other characters. Tone may be formal or informal, playful, intimate, ironic, condescending, zealous, tender—as far and wide as feelings can range. It emerges from the complex interactions among words, images, and allusions, from the sounds of the language—from all the artistic talents employed by the writer. Tone is inseparable from the meaning of a poem. Voice / Persona / Speaker: Poet W.B.Yeats said that the poet “never speaks directly as to someone at the breakfast table.” Thus, we speak of the “voice” or “speaker” in a poem or a novel as that character or second self through whom the story is told, the ideas conveyed. In some cases, the speaker is less distinctive, simply serving as the voice. Other times, the speaker is a crucial contributor to the whole meaning of the poem. (See Robert Browning’s “My Last Duchess” or “Porphyria’s Lover,” and E. A. Robinson’s “Richard Cory.”) SOURCES USED: A HANDBOOK TO LITERATURE by William Harmon and C. Hugh Holman HOW TO READ A POEM by Edward Hirsch INTRODUCTION TO THE POEM by Robert Boynton and Maynard Mack MERRIAM WEBSTER’S READER’S HANDBOOK