Framing violence: The political function of riots in Northern India

advertisement

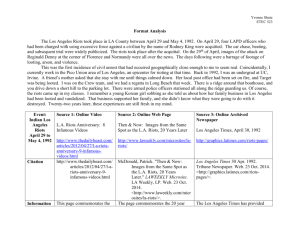

Karla López de Nava PS311 Week 9 Framing violence: The political function of riots in Northern India Why do caste and communal riots persist in India? Why have Hindu-Muslim conflicts become endemic? Do these conflicts present a serious threat to Indian national unity? These are the questions that Paul R. Brass explores in his book, Theft of an Idol1. By carefully studying the information collected on five incidents that occurred in Northern India, Brass narrates the different discourses, interpretations, representations and framings that politicians, villagers, police officers and local authorities attach to a riot, and the reasons that lie beneath the “labeling” of riots. Most importantly, he identifies the use of violence as a political weapon. The purpose of this paper is to briefly summarize Brass’ most important findings and the contribution that his analysis makes to the ethnic violence literature. Brass uses case study research to explain the persistent occurrence of riots in India. Focusing on five incidents that took place in the state of Uttar Pradesh, he explains why they were interpreted in different ways, and why some of these riots managed to capture national media coverage, while others, even though they may have merited national attention, did not. There are five events that Brass identifies as the precipitating incidents of the riots: 1. The theft of an Idol in the district of Aligarh. 2. The “alleged” rape of a girl in the district of Meerut. 3. A bus runs over a woman in Narayanpur. 1 Paul R. Brass, Theft of an Idol. Princeton University Press.1997 1 4. A brawl between police and villagers of a backward caste in Gonda district. 5. The demolition of a mosque in Ayodhya. His main argument is that the “official” versions of the caste and communal riots are constructions that are usually far removed from the actual events that originated the incident. The reason for this gap is that the framing of riots benefits political parties and dominant political ideologies.2 This labeling is useful to win political support and justify the exercise of state authority. A case in point is the Narayanpur incident that originated when an old woman was run over by a bus.3 The event evolved into a violent confrontation between police and villagers (mostly Muslims and Harijans4); some of the latter were severely beaten and put in jail. This violent episode was conveniently used by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi to attack the local opposition-run government. She accused the government of inefficiency and pointed to its inability to control a brutal police force intent on attacking “weaker sectors” of society. In the end, the local government was removed, and the Congress Party rose to power. This incident was not of the communal (Hindus versus Mulsims) type, but it was surrounded, as Hindu- Muslim and other ethnic riots are, by politician’s discourses5 that aim to attack, discredit and blame their political opponents in order to gain some sort of political advantage. Thus, politicians appeal to religious sentiment and ethnic identity to gain a broader base of support, and they use riots as perfect 2 Although Brass mentions that most of the actors involved in the riot, including the villagers, have incentives for playing their part, there are few “innocent” victims. 3 The woman was the grandmother of two children. After she was killed, the villagers demanded that the bus driver pay a financial compensation to the children. The driver failed to pay, so the villagers stop another bus driver. The police arrive at the scene, things get violent, and the struggle erupts. 4 Scheduled castes. 5 There are different discourses depending on the type of riot. Some examples of discourses are: the discourse of caste and community, the discourse of law and order, the discourse of profit, and the religion discourse, among others. 2 opportunities to do so. Every group has a different interpretation of the incidents. Their aim is to frame the incidents to their own advantage. But why are some places more prone to riots than others? Brass contends that cities that have an institutionalized riot system are more likely to experience endemic riots. He defines an institutionalized riot system as an informal network of persons who maintain communal, racial and other ethnic relations in a state of tension. At the center of the network are what Brass calls “the fire tenders or riot professionals,” i.e., people whose primary function is to always keep the tension alive, and in some cases transform small incidents into categorical riots, and groups trained in the use of weapons (police, for example). Brass mentions that there are some special circumstances that favor the emergence of riots: before and during elections, and during movements of mass mobilizations, especially when the political balance between contending forces appears to be changing; that is, when political opportunities are such that a riot increases the support for a political movement, or decreases the support for another. In this view, riots are partially planned, although some groups try to make them look spontaneous. Brass compares the riots as a super production in which different actors with particular goals and incentives interact6. Some of the actors may decide to enter into coalitions, such as the one made sometimes by the police force and a political party. But every actor knows the role he is supposed to play. Every actor has its truthful version of the final outcome, so in the end, all that is left are multiple and subjective interpretations. There are no truths, just beliefs. 6 This riot system theory sounds almost like a simultaneous game, where every player has certain incentives, an expected utility function, and acts upon the expectations he has of how the rest of the players will act. 3 Concerning the question of why some riots get national media coverage and others do not, Brass argues that the transformation of riots into categorical events only takes place when this step provides political advantage for some political party or parties: “What matters is who stands to gain and who stands to lose from publicizing such events”7 Brass concludes that not only do the different discourses and framings become a substitute for authorities’ inaction, but that they also become the means of perpetuating the same riot system. Discourses only call to attention the politically useful riots, but leave all the other incidents of violence unattended. Summarizing Brass’ argument, it is apparent that the struggle of discourses is a struggle for power, and some of these discourses or framings empower some individuals, and at the same time, weaken others. This is the reason why so many interpretations emerge from one unique event and, most importantly, this is why certain groups have an incentive to instigate or perpetuate riots. The two most important factors that favor the perpetuation of violence are: an institutionalized riot system and the actions of the local administrative authorities. With his narrative, Brass establishes some of the elements that contribute to the perpetuation of violence. Although he never explains what causes the violence in the first place. That is, he never asserts why and how institutionalized riot systems arise. Still, he describes in a compelling way the political manipulation of violence, especially near elections or when there is a change in the political balance. His detailed analysis also helps to distinguish the different power relations that lurk behind the discourses and contextualizations. 7 Paul R. Brass, Theft of an Idol. 4 Even though his narrative does not analyze the origins of the institutionalized riot system, it succeeds in explaining the function of violence as a strong political weapon, thereby providing an explanation of why some riots are turn into categorical events, while others are left in the dark. He also presents a clear picture of how politicians can manipulate existing cleavages to gain political support. 5