In Deep Water on the Oil Spill Disaster in Gulf of Mexico

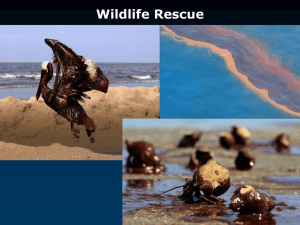

advertisement

The Deepwater Horizon disaster has put three urgent questions before the country. What happened? How did we arrive at this point? And: where must we go from here? The way we answer these questions will have a profound impact on the future of the Gulf of Mexico, its people and, indeed, Americans everywhere. The implications for our economy and national security, our environment, and our entire way of life can hardly be overstated. This book is an attempt to address those questions, providing answers where they exist, clues where they do not and guidance as to where we might find them. As the questions are urgent, the book is meant to be timely, a first draft of sorts. The narrative that we tell is the story so far, with much remaining to discover and learn. We hope that various analyses underway, as well as the president’s commission investigating the blowout (on which NRDC President Frances Beinecke serves), will bring us all to a more thorough understanding. On the face of it, what happened is clear: the fourth-largest corporation in the world drilled a well beneath a mile of water in the Gulf of Mexico. Operating at the frontier of knowledge in conditions more challenging than even deep space, this well was inherently dangerous. There were a series of judgments, operations and technological shortcomings running from the planning and design of the well to the effort to seal it that set the stage for disaster. When the well blew out on the night of April 20, equipment designed to be that last line of defense against disaster failed to shut down the well. Eleven men were killed that night and more than two hundred million gallons of crude oil gushed into the ocean during the three months it took for oil company, formerly known as British Petroleum, to cap the well. More than six hundred miles of coastline were oiled and a slick the size of South Carolina covered the fertile Gulf. Ocean, coastal and wetlands habitat and birds, fish, marine mammals, sea turtles and other animals and plants were damaged or destroyed. Thirty-seven percent of American waters in the Gulf were closed to fishing, thousands of watermen and others were thrown out of work; and the future of a complex and vital region was cast into uncertainty. Our country arrived at this point because our demand for oil has driven companies like BP into deeper and riskier Gulf waters at precisely the time the political consensus had broken down for the public safeguards we need to protect our safety, health and environment. Our watchdog agencies, in short, were defanged. And so, just as companies pushed the outer limits of their technological capability and operational expertise to drill for oil in water up to two miles deep, the agency responsible for ensuring the industry’s safety was steadily becoming compromised, losing its ability to keep up. That agency, the Minerals Management Service, an arm of the Department of the Interior, was addled by rules and authority that were yeas behind the fast-changing offshore oil industry. The agency had five dozen inspectors to keep tabs on four thousand offshore platforms, some of which serviced more than two dozen wells, across the Gulf of Mexico. The close-knit culture of the region, and a near-incestuous relationship between the agency and the industry it was supposed to oversee, created an atmosphere in which oil company engineers sometimes penciled in their own responses to inspection forms and federal inspectors later traced over those replies in ink. Offshore oil companies treated inspectors to private hunting expeditions, skeet shoots and fishing trips. Beyond such cultural proclivities, there were institutional mandates as well. President George W. Bush and his vice president Dick Cheney were both oil company executives before they came to the White House. Waging war in Iraq, home to the fourth-largest proven oil reserves in the world, those men also put in place energy policies aimed at boosting domestic production. In the Gulf, that meant speeding the permitting process for offshore wells like the one BP lost control of in April, and waiving requirements for adequate environmental review and sufficient oversight of blowout response plans. And what was happening in the Gulf was reinforced by similar developments around the country. Most efforts to conserve or use energy more efficiently were stymied, in part due to the opposition of the oil, gas and coal companies. At the same time, agencies Congress had ordered to protect the public were underfunded, staffed with industry allies and intimidated by attacks in the press. When BP’s Macondo well blew out, the company had no idea how to stop the runaway well and no equipment in place to cap it. From the president on down, Americans watched in helpless fury as two million gallons of crude oil a day gushed into some of the most diverse and productive fisheries in the world. The Gulf is home to scores of species of fish, from the majestic bluefin tuna to the common carp, numerous endangered species, such as whales and sea turtles, and birds both migratory and resident. It is the source of seventy percent of oysters and shrimp produced in this country and hundreds of millions of pounds each year of snapper, grouper, tuna and other seafood. Drilling for oil in the Gulf of Mexico, it turned out, is an activity that puts an irreplaceable resource at risk. There are only two rational responses: reduce the risk and reduce the need for the activity. We can do both; we must do both – or else further catastrophe awaits. In this book, we show how we can make offshore drilling safer by investing in the safeguards we need, the institutions required to enforce those safeguards and the professionals we can count on to protect our safety, health and environment. I am not a technical expert and this book does not purport to offer engineering solutions: rather, the book suggests structural changes that will ensure that we have adequate technical experts with the ability and authority to protect us. And we show how we can cut our consumption of oil in half while reducing the threats to habitat and health. The conclusions I draw are informed by a thirty-year environmental law career that began on the Gulf Coast. Working for the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund, I helped bring a lawsuit against the federal government regarding the environmental impact of a planned bridge at Dauphin Island, in Alabama’s Pelican Bay. We lost the case and the bridge was built, but I developed an abiding interest in this rich and robust region and the endless complexity of its wildlife and habitat. Working on the case also inspired me to go to Columbia University Law School, where I learned that, if we’re right on the law and the science, we can accomplish an enormous amount for our environment. I took that adage to heart, creating the environmental prosecution unit at the New York City Law Department. Our first big case addressed New York’s biggest oil spill, when an Exxon pipeline burst. The case resulted in major operational changes and wetlands restoration. I later headed the New York Attorney General’s Environmental Protection Bureau, with an excellent staff of forty lawyers and ten scientists, where I saw both a wider range of fossil fuel energy impacts and opportunities for a cleaner future. As executive director of the NRDC, I oversee the work of more than four hundred dedicated environmental advocates, lawyers and scientists supported by 1.3 million members and activists nationwide. From the early days of the BP blowout, we recognized the potential threat it posted to deep ocean, coastal waters, shore-line, wetlands, estuaries and bays, as well as to our air, inland fresh waters marine life, aquatic life and birds. This book pulls together the work of an entire staff of dedicated professionals, including dozens who have been directly involved in our oil spill response efforts from the opening days of the disaster. The Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989 focused the NRDC’s attention on the risks of producing and transporting oil in the frigid Arctic waters far north of the Gulf of Mexico. Our advocacy succeeded in putting in place a twenty-year moratorium on drilling in the Arctic and many of our coastal waters, but we did not succeed in protecting the Gulf, which has seen decades of environmental degradation in the name of drilling and other commercial activities. Hurricane Katrina reawakened the nation to the decades of harm experienced in the lower reaches of the Mississippi delta, and the impact that deterioration had been having on the Gulf. Collapses in coal mines killing dozens of workers, spills of toxic coal ash, and gas contamination of water supplies have been constant reminders. The Macondo blowout is another national wake-up call, a sobering plea for action on the greatest environmental challenge of our time: finding a way out of the economic and social model we’ve built around fossil fuels, and forging a future built instead around the clean energy technologies of tomorrow.