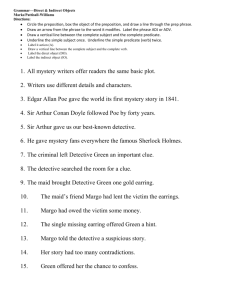

Directions and All Articles

advertisement

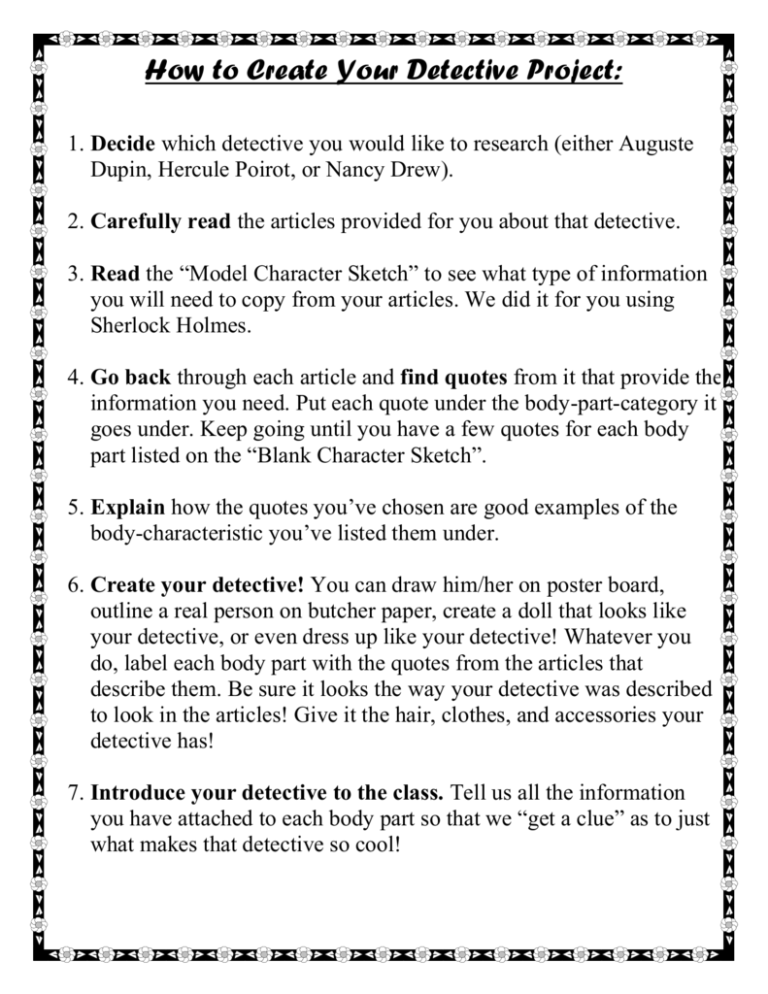

How to Create Your Detective Project: 1. Decide which detective you would like to research (either Auguste Dupin, Hercule Poirot, or Nancy Drew). 2. Carefully read the articles provided for you about that detective. 3. Read the “Model Character Sketch” to see what type of information you will need to copy from your articles. We did it for you using Sherlock Holmes. 4. Go back through each article and find quotes from it that provide the information you need. Put each quote under the body-part-category it goes under. Keep going until you have a few quotes for each body part listed on the “Blank Character Sketch”. 5. Explain how the quotes you’ve chosen are good examples of the body-characteristic you’ve listed them under. 6. Create your detective! You can draw him/her on poster board, outline a real person on butcher paper, create a doll that looks like your detective, or even dress up like your detective! Whatever you do, label each body part with the quotes from the articles that describe them. Be sure it looks the way your detective was described to look in the articles! Give it the hair, clothes, and accessories your detective has! 7. Introduce your detective to the class. Tell us all the information you have attached to each body part so that we “get a clue” as to just what makes that detective so cool! Model Character Sketch Head: Brainstorm- What are this character’s intellectual characteristics? Quotes: “…vigilant and deductive” (Lederer 3). “…aesthete with a cool creative touch…” (Ellis 1). Explanation: These two quotes list examples of Sherlock’s intellectual characteristics like vigilance and creativity. Right Hand: Right-Hand Man- Who helps this character? Quotes: “His sober, credulous companion, Dr. Watson, narrates most of the Sherlock Holmes stories (Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia 1). “…the game was always afoot with Holmes and Watson” (Ellis 1). Explanation: Both of these quotes list Dr. Watson as not only the narrator of the story but a person who often accompanies Holmes in his adventures, making him his likely partner. Left Hand: Handy Dandy- What are this character’s skills? Quote: “…Sherlock Holmes, ‘the most perfect reasoning and observing machine’” (Ellis 1). “…Holmes solves all his extraordinarily complex cases through ingenious deductive reasoning” (Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia 1). Explanation: These two quotes both suggest that Holmes’ most obvious and often-used skills are brilliant reasoning and detailed observation. Stomach: Blow to the Gut- What are this character’s inner weaknesses? Quotes: “…workaholic…” (Ellis 1). “penchant for…morphine and cocaine…” (Ellis 1). Explanation: Though Holmes is said to have few weakness, these two quotes show that he works too much and compensates with drugs. Left Leg: A Leg to Stand On- Why is this character historically/socially relevant (as in, why do we still know/read about him today?) Quotes: “…Sherlock Holmes, the world’s first consulting detective” (Lederer 1). “…one of the first detectives to base his work squarely on scientific methods” (Lederer 1). Explanation: These quotes suggest that Doyle’s detective is unique because no other fictional detective had been a “consulting” detective, nor had any other ever used the scientific method to solve crime, which makes Holmes historic. Right Leg: Just Kickin’ It- What are this character’s interests/hobbies? Quotes: “…penchant for violins…” (Ellis 1). “…pipe-smoking…” (Ellis 1). Explanation: Aside from solving mysteries, these quotes show Holmes has everyday interests as well. Left Foot: Strong Foundation- Who created this character? (provide a short bio) Bio:Arthur Conan Doyle was born in 1859 in Edinburgh, England. He became a doctor in the early 1880s, though he was more interested in writing. He created the popular character Sherlock Holmes in 1887, and he quit his job as a doctor three years later. He also wrote historical love stories, political lectures, and research-based novels on spiritualism. He was knighted for his valiant efforts in literature in 1903, and continued writing until his death in 1930 (Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia 1). Explanation: No explanation needed Right Foot: Best Foot Forward- Why did the author create this character/what was the author’s inspiration? Quotes: “Inspired by Edgar Allan Poe’s detective Dupin and the neat dovetailing of plots in Emile Gaboriau’s M. Lecoq tales, Doyle added the ‘science’ of detailed observation…” (Ellis 1). “…his model for Sherlock Holmes, the amazing lecturer Dr. Joseph Bell, whose deductive powers in sizing up patients from their behavior, physiognomy, accent, and clothing were legendary” (Ellis 3). Explanation: The first quote shows Doyle was influenced by other detective authors; however, as stated in the second quote, the specific character of Sherlock Holmes was inspired by a real person. EXTRA CREDIT: Mouth: Say What?- Give a quote from this character about who they are (and the context in which it appears) “My name is Sherlock Holmes. It is my business to know what other people don’t know.” –The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle Blank Character Sketch—Provide CITED quotes for each (at least two per body part) Head: Brainstorm- What are this character’s intellectual characteristics? This is where you are listing what the character’s mind is like. Are they smart/stupid? Are they creative/boring? Quotes: Explanation: Right Hand: Right-Hand Man- Who helps this character? This could be a partner, a friend, a police officer, or anyone who consistently comes to the aid of your detective. Quotes: Explanation: Left Hand: Handy Dandy- What are this character’s skills? Slightly different from the facts you put on the head; what are the things this detective is good at? Yes, you can using “solving crime” as one of them (though that shouldn’t be the only one). Quotes: Explanation: Stomach: Blow to the Gut- What are this character’s inner weaknesses? What is this character bad at? If they are good at many skills, what are their personal weaknesses? Do they get scared or are they sometimes mean? Quotes: Explanation: Left Leg: A Leg to Stand On- Why is this character historically/socially relevant (as in, why do we still know/read about him today?) What made this character “the first” or “the best” of their time? Why are they still important and beloved today? Quotes: Explanation: Right Leg: Just Kickin’ It- What are this character’s interests/hobbies? You can use “crime-solving” for one interest, but what else does this detective like to do in their spare time? Quotes: Explanation: Left Foot: Strong Foundation- Who created this character? (provide a short bio) This should include the author’s name, birth/death date, where they were born, what it was like for them growing up, what sort of jobs they had as an adult, or anything that informs us how they turned out like they did. This should be paraphrased (DO NOT PLAGIARISE OR SUMMARIZE) from your source, but don’t forget the citation at the end! Right Foot: Best Foot Forward- Why did the author create this character/what was the author’s inspiration? Was there another popular character that the author based their detective on? Were there other stories like this one at the time? Why did the author decide this character needed to exist? Quotes: Explanation: EXTRA CREDIT: Mouth: Say What?- Give a quote from this character about who they are (and the context in which it appears). Dupin Source 1 “Dupin,C.Auguste.” Merriam-Webster’s Encyclopedia Of Literature (1995): N.PAG. Literary Reference Center. Web. 23 Apr. 2014. Dupin, C. Auguste Fictional detective appearing in three stories by Edgar Allan Poe. Dupin was the original model for the detective in literature. Based on the roguish FranÇois-Eugène Vidocq, onetime criminal and founder and chief of the French police detective organization Sûreté, C.Auguste Dupin is a Paris gentleman of leisure who uses “analysis” for his own amusement to help the police solve crimes. In the highly popular short stories THE MURDERS IN THE RUE MORGUE and THE PURLOINED LETTER, as well as the less successful “The Mystery of Marie Roget,”Dupin is depicted as an eccentric, a reclusive amateur poet who prefers to work at night by candlelight and who smokes a meerschaum pipe—foreshadowing the nocturnal Sherlock Holmes. Like Holmes, Dupin is accompanied by a rather obtuse sidekick, though Dupin’s companion, unlike Dr. Watson, remains a nameless narrator. Poe’s three stories of “ratiocination”—to become Holmes’s “deduction”—introduced a new genre to world literature: the detective story. Dupin Source 2 Bouchard, Jennifer. "Edgar Allan Poe’s "The Purloined Letter." Literary Contexts In Short Stories: Edgar Allan Poe's 'The Purloined Letter' (2008): 1. Literary Reference Center. Web. 23 Apr. 2014. Published in 1845, "The Purloined Letter" by Edgar Allan Poe is one of the first published detective stories. The story features C. Auguste Dupin, a witty intellectual with a knack for solving crimes. Dupin comes to the aid of the Paris police department in helping to secure a letter which has the power to publicly dishonor the Queen. Author Supplied Keywords: Letter; Logic; Minister; Paris; Police; Prefect; Purloined; Royal Plot Synopsis In the short story, "The Purloined Letter," the narrator retells the account of how his friend, C. Auguste Dupin, solves a mystery regarding a letter stolen from the royal family. It begins in Dupin’s Paris apartment as the narrator enjoys a pipe and the quiet company of his friend when they are interrupted by Monsieur G -- --, the Prefect of the Paris police. The Prefect has come to confide in Dupin in a matter of utmost secrecy and ask for his advice. The Prefect explains that a theft has recently occurred at the royal headquarters and diplomatically implies that the Queen has had an affair or some indiscretion that she is trying to hide from the King. Her secret was threatened when the King entered her bedroom while she was reading a revealing letter. About the same time she tried to hide the letter, the Minister D—entered the room and from the Queen’s behavior figured out her secret. Determining the letter to be a great source of power over her, he found a way to swap the letter with one of similar appearance and take the original from her possession. The Minister has been blackmailing the Queen ever since. The Prefect tells the men that he has since searched every inch of the Minister’s residence but cannot find the letter. He says the Minister is a poet, which makes him a fool; the Prefect is confounded as to how his police department has not discovered the letter yet. Dupin asks the Prefect to recount the details of his search so that he can better assist him. He explains that he and his crew took apart furniture, searched drawers, walls, floors, books, etc. He is certain that they did not miss an inch of the Minister’s home. Dupin then asks the Prefect to describe the letter, which he does before leaving in disappointment that Dupin cannot be of more assistance. One month later, the Prefect returns to visit Dupin and confesses that he still cannot find the purloined letter. Dupin asks him if he really has done all that he can. The Prefect replies that he has and says that he would pay 50,000 francs if he could get the letter. Dupin asks him to write him a check and when he does, he produces the letter for the Prefect who then leaves speechless. The narrator asks Dupin how he found the letter who goes on to explain that the Prefect underestimated the Minister’s intellect because he believes that all poets are fools. Dupin, knowing this to be false, had estimated that the Minister would anticipate the Paris police ransacking his house. Therefore, Dupin knew he would not hide the letter in any of the usual places. Dupin then explains how he went to the Minister’s house himself to search for the letter. He found it in an old card rack placed in plain site, however disguised as a dirty and unimportant letter. Dupin then excuses himself but intentionally leaves his snuffbox behind so he has an excuse to return the next day. Upon his return, Dupin tells the narrator, that he paid someone to create a disturbance in the street to distract the Minister while Dupin switched the letter with a worthless one. So that the Minister would know who outwitted him, he wrote in the letter the following clue: " -- -- -- -- Un dessein si funeste, S'il n'est digne d'Atrée, est digne de Thyeste. They are to be found in Crébillon's Atrée." The translation of the passage is, "If such a sinister design isn’t worthy of Atreus, it is worthy of Thyestes," revealing clever Dupin to be connected to, possible the brother of, the cunning Minister D-. Symbols & Motifs The letter in "The Purloined Letter" serves as a symbol of a privacy that has been invaded as well as a power struggle. The public release of the letter would disgrace the royal family and thus the cunning Minister uses it as a means to gain power over the Queen. "The Purloined Letter" opens with a latin maxim, "Nil sapientiae odiosius acumine nimio," translated as "nothing is more hateful to wisdom than excessive cleverness." The story truly is a battle of wits as Dupin proves to outsmart both the Prefect and the thief. The letter that Dupin replaces with the purloined letter so as to avoid an early detection by the Minister made reference to the brothers Atreus and Thyeste of ancient Greek lore. In the myth, the brothers were constantly in competition with one another. In an act of revenge because Thyeste had an affair with Atreus’ wife, Atreus killed Thyeste’s children, cooked them and served them to Thyestes (Hunter). Eventually, Thyeste had a son who grew up and killed Atreus (Hunter). The reference to these brutally competitive brothers suggests a symbiotic relationship between Dupin and the Minister. Historical Context "The Purloined Letter" is one of three stories to feature C. Auguste Dupin, the world’s first literary detective. He first appears in "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" written in 1841 and considered by many to be the first detective story, and "The Mystery of Marie Roget" both of which were alluded to at the beginning of the story. The actual profession of detective had just been establis hed in the early 1800s and Poe was inspired by Francois-Eugene Vidocq who, in 1817, founded the first detective bureau (Poe and Ratiocination). Societal Context In a letter to James Russell Lowell, Poe used the term ratiocination to refer to "The Purloined Letter." Ratiocination is defined as the process of exact thinking or reasoning (Merriam Webster). The first detective stories are referred to as tales of ratiocination. Poe is quoted as saying, "Truth is often and in very great degree, the aim of the tale. Some of the finest tales are tales of ratiocination" (Poe and Ratiocination.) He was proud of his capacity for logic and analysis. He loved solving problems and puzzles, much like his detective Dupin (Poe and Ratiocination). However, he eventually tired of these stories and stopped writing in the genre that he created (Poe and Ratiocination). Poe took special care to note that the villain in "The Purloined Letter" is a poet and thus, according to the Prefect, one step away from a fool. Dupinagrees but acknowledges that he himself has dabbled in the art. He therefore does not underestimate the poet’s abilities at reason and is able to defeat the Minister and outsmart the Prefect. Poe is able to acknowledge society’s negative views of the poet as a trivial profession, unworthy of any intellectual recognition. Yet he is also makes a statement in the sense that the character representative of the public, the Prefect, is unable to solve the crime. He cannot outsmart the poet but Dupin can due in part to his respect for the abstract reasoning abilities of a poet. Religious Context "The Purloined Letter" does not have a specific religious context. Scientific & Technological Context "The Purloined Letter" does not have a specific scientific or technological context. Biographical Context Edgar Allan Poe was born in Boston 1809 to a traveling actor and actress. When Poe was born, his father abandoned his mother ("Edgar Allan Poe"). She died a few years later while on tour in Virginia and he was taken in by a wealthy couple in Richmond, John and Frances Allan, who could not have children. While the Allans cared for and educated Poe, they never formally adopted him and John Allan never warmed to his foster son. Once in college at the University of Virginia, Poe accrued a large gambling debt and John Allan withdrew him from school ("Edgar Allan Poe"). After a heated argument, Poe left home and moved to Boston. In 1827, in Boston, Poe published a volume of poetry entitled "Tamerlane." The book did not sell well and, in need of money, Poe joined the army. Poe did not like the army but was promoted to the rank of sergeant major, and with the Allans’ help, he enrolled in the US Military Academy at West Point ("Edgar Allan Poe"). In 1829, Poe published another book of poems "El Aaraaf" which received positive reviews. While at West Point, Allan’s wife died and he remarried. Since Poe knew he would no longer be considered as Allan’s heir, Poe withdrew from West Point, and moved in with his aunt in Baltimore, Maryland ("Edgar Allan Poe"). In 1835, Poe married his chronically ill thirteen-year old cousin, Virginia. Poe worked as an editor at various magazines while trying to succeed as a writer ("Edgar Allan Poe"). He wrote only one full-length novel, "The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym" but his short stories became his claim to fame. Poe is given credit as the creator of the modern detective story with such stories as "The Gold Bug," "The Murders in the Rue Morgue," and "The Purloined Letter." Other stories, such as "The Tell-Tale Heart" and "The Cask of Amontillado" explore the inner demons of a person’s mind. In 1845, he published the poem "The Raven" which brought him fame and solidified his career as a writer. Unfortunately, alcohol abuse and financial instability continued to plague Poe throughout his life. When his wife died in 1847 or tuberculosis, Poe grew more unstable ("Edgar Allan Poe"). In 1849, Poe disappeared and a week later he was found, battered and delirious, near a Baltimore tavern. He died four days later at the age of 40 and his death remains a mystery to this day. Poirot Source 1 "Dame Agatha Christie." Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6Th Edition (2013): 1. Literary Reference Center. Web. 23 Apr. 2014. Christie, Dame Agatha, 1890–1976, English detective story writer, b. Torquay, Devon, as Agatha Mary Clarissa Miller.Christie's second husband was the archaeologist Sir Max Mallowan, and she gained much material for her later novels during his excavations in the Middle East. An extraordinarily popular author, Christie wrote over 80 books, most of them featuring one of her two famous detectives; Hercule Poirot, an egotistical Belgian, and Miss Jane Marple, an elderly spinster. Her novels, noted for their skillful plots, include The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920), The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926), Murder on the Orient Express (1934), Death on the Nile (1937), And Then There Were None (1940), Death Comes as the End (1945), Funerals Are Fatal(1953), The Pale Horse (1962), Passenger to Frankfurt (1970), Elephants Can Remember (1973), and Curtain (1975); her plays include The Mousetrap (1952), one of the longest-running plays in theatrical history, and Witness for the Prosecution (1954). Christie also published novels under the pseudonym Mary Westmacott. She was named Dame Commander, Order of the British Empire, in 1971. Poirot Source 2 Huebert, Susan. "Hercule Poirot, Agatha Christie's Detective." Suite. N.p., 12 Mar. 2010. Web. 23 Apr. 2014. <https://suite.io/susan-huebert/36z62cc>. Hercule Poirot, Agatha Christie's Detective One of the world's most famous fictional detectives is Hercule Poirot, created by the British writer Agatha Christie in 1920 and still popular around the world. When fans of the mystery genre hear the term, “little grey cells,” only one fictional character comes to mind: British writer Agatha Christie’s Belgian detective, Hercule Poirot. Since his creation in 1920, the quirky little detective, known for his foppish clothes, self-confidence bordering on arrogance, unique mannerisms, and brilliant detective abilities, has captured the minds of mystery enthusiasts around the world and has helped make Agatha Christie one of the most widely-read authors in the world. Agatha Christie and the First Hercule Poirot Book According to the official Agatha Christie website, the famous author’s career started at the prompting of her sister, Madge, who urged her to try writing a novel. She drew on her experiences during the First World War to write The Mysterious Affair at Styles, the first book to feature the detective who would be part of more than thirty novels, as well as many short stories. The final Poirot book, Curtain, was published after Christie’s death. Settings range from a cruise ship on the Nile River to elegant English country houses to the streets of London, all brought to life by a cast of characters including country doctors, aristocrats, and schoolgirls. The Word IQ website describes the characteristics that make Hercule Poirot unique, especially in contrast to some of the recurring characters in the novels. Poirot’s dandified appearance, egg-shaped head, and frequent references to the “little grey cells” of the brain lead many criminals to underestimate his powers of deduction, and even his good friend, Arthur Hastings, rarely understands the great detective’s process of reasoning. Whatever the case, Hastings is always several steps behind his friend and is astonished at the solutions to the mysteries. Another friend of Poirot’s is Ariadne Oliver, who provides comic relief in several books, including Cards on the Table and Third Girl, with her strong opinions and obsession with eating apples. Although she is a mystery writer, she is unable to apply her fictional detective’s deductive skills to her her own experiences. In each mystery, she is surprised by the ending. Poirot Source 3 "About Poirot." Agatha Christie: The Official Information and Community Site. N.p., n.d. Web. 23 Apr. 2014. <http://www.agathachristie.com/christies-work/detectives/poirot/1>. ABOUT POIROT It was in 1920 that Hercule Poirot made his first appearance in The Mysterious Affair at Styles, called upon by his old friend Lieutenant Hastings, who would come to be the Watson to Poirot's Holmes. In fact, Agatha Christie later wrote that Poirot's introduction to detective fiction was not at all how he himself would have liked. "Hercule Poirot first," he would have said, "and then a plot to display his remarkable talents to their best advantage." But it was not so. Christie had already mentally drafted the story for The Mysterious Affair at Styles, yet it lacked a detective. She took note of Belgian refugees in Torquay in 1904 and it wasn't long before she had a character in mind, "a former shining light of the Belgian police force". It was a light that proved impossible to extinguish, foiling Poirot's multiple attempts at retirement as well as any chance he gets for a holiday. Poirot would be the first to call himself a great man - he has never been known for his modesty - but with such success in his career, it is difficult to argue with him. He finishes each case with a dramatic dénouement, satisfying his own ego and confirming to all that he is truly "the greatest mind in Europe." His love of elegance, beauty, and precision, as well as his eccentric mannerisms are often ridiculed by the local bumbling policemen, but it is always Poirot who has the last word. Agatha Christie never imagined how popular Poirot would become, nor how many stories she would write about him. He stars in 33 novels and 54 short stories, including some of Christie's most successful such as Murder on the Orient Express and Death on the Nile. One of Christie later regrets was that Hercule Poirot began his literary life too mature: "the result is that my fictional detective is well over a hundred by now." And it is no secret that character and author did not always see eye to eye. Christie grew tired of Poirot's idiosyncrasies so much so that she wrote Curtain: Poirot's Last Case in the 1940s. It was locked in a safe until 1974 when it was finally published, earning Poirot a well-deserved obituary in The New York Times; he is the only fictional character to have received such an honour. The first actor to take on the role of the little Belgian was Charles Laughton in 1928 in the theatrical debut of Alibi. Austin Trevor was the first Poirot on screen in 1931, and went on to star in three films. There was Tony Randall in 1965 and Academy Award nominee Albert Finney in the all-star classic Murder on the Orient Express in 1974. The great Peter Ustinov, winner of two Academy Awards, played Poirot in six films and despite not physically resembling the character is still much loved worldwide. There was even a Japanese anime version of Poirot, broadcast in 2004. Perhaps, however, the actor most synonymous with Hercule Poirot is David Suchet, who first took on the role in 1989. Christie never saw David Suchet's portrayal but her grandson, Mathew Prichard, thinks that she would have approved; Suchet balances “just enough of the irritation that we always associate with the perfectionist, to be convincing!” Suchet's final series finished filming in 2013 and marks 25 years of being Poirot. Christie wrote in an article in 1938 that Hercule Poirot's favourite cases included The Murder of Roger Ackroyd and Lord Edgware Dies, whereas he regards Three Act Tragedy as "one of his failures. Although most people do not agree with him." She concluded that while they have had their difficulties, "We are friends and partners. I am beholden to him financially. On the other hand he owes his very existence to me." A sentiment which Poirot himself would surely deny. Drew Source 1 Fisher, Jennifer. "The Mysterious History of Nancy Drew." The History of Nancy Drew. N.p., 1 Jan. 2014. Web.23 Apr. 2014. <www.nancydrewsleuth.com/ history.html>. Th e My s t e r i o u s H i s t o r y o f N a n c y D r e w F o r o ve r timeless quality war-torn 1940’s t h a t h a ve l e d t o 8 0 ye a r s , N a n c y D r e w h a s t r a i l b l a ze d t h r o u g h g e n e r a t i o n s , h e r e n d u r i n g a n d f o r e ve r a huge part of her appeal. She endured through the depression era of the 1930 ’s and the w h e n m a n y o t h e r s e r i e s w e r e d i s c o n t i n u e d a n d w a n e d i n p o p u l a r i t y. Th e r e a r e m a n y f a c t o r s t h e s u c c e s s o f N a n c y. I n t h e b e g i n n i n g s h e w a s j u s t a n a m e . J u s t a f e w p a g e s o f p l o t a t t h e h a n d s o f c r e a t o r E d wa r d S t r a t e m e ye r a n d h i s S t r a t e m e ye r S yn d i c a t e . S h e d e b u t e d a t a t i m e wh e n g i r l s we r e r e a d y f o r s o m e t h i n g d i f f e r e n t — s o m e t h i n g t h a t g a ve t h e m h i g h e r i d e a l s . N a n c y wa s t h e e m b o d i m e n t o f i n d e p e n d e n c e , p l u c k , a n d i n t e l l i g e n c e a n d t h a t w a s wh a t m a n y l i t t l e g i r l s c r a ve d t o b e l i k e a n d t o e m u l a t e . I t wa s Mi l d r e d A . W i r t B e n s o n , wh o b r e a t h e d s u c h a e i s t y s p i r i t i n t o N a n c y ’ s c h a r a c t e r . Mi l d r e d w r o t e 2 3 o f t h e o r i g i n a l 3 0 N a n c y D r e w My s t e r y S t o r i e s . I t wa s t h i s c h a r a c t e r i za t i o n t h a t h e l p e d m a k e N a n c y a n i n s t a n t h i t . T h e S t r a t e m e ye r S y n d i c a t e ’ s d e v o t i o n t o t h e s e r i e s o v e r t h e ye a r s u n d e r t h e r e i g n s o f H a r r i e t S t r a t e m e ye r A d a m s h e l p e d t o k e e p t h e s e r i e s a l i ve a n d o n s t o r e s h e l ve s f o r e a c h s u c c e e d i n g g e n e r a t i o n o f g i r l s a n d b o ys . N a n c y w a s a l wa ys H a r r i e t ’ s f a vo r i t e . H a r r i e t ’ s d e d i c a t i o n t o t h e s e r i e s h e l p e d t r e m e n d o u s l y i n e n s u r i n g t h a t N a n c y i s s t i l l a r o u n d t o d a y a n d l i k e l y wi l l b e f o r m a n y y e a r s t o c o m e . Th e o r i g i n a l p u b l i s h e r s , G r o s s e t & D u n l a p , p l a ye d a h u g e r o l e i n t h e s u c c e s s o f N a n c y D r e w . F r o m t h e i r m a r k e t i n g s t r a t e g i e s t o t h e i r m a n y s a l e s m e n , t h e y k e p t t h e s e r i e s i n wi d e s p r e a d d i s t r i b u t i o n s o t h a t c h i l d r e n f r o m a l l a r o u n d t h e c o u n t r y a n d l a t e r i n f o r e i g n c o u n t r i e s c o u l d d i s c o ve r N a n c y ’ s e xc i t i n g w o r l d . I t wa s G r o s s e t & D u n l a p wh o h e l p e d c h o o s e t h e o r i g i n a l a r t i s t , R u s s e l l H . T a n d y , t o i l l u s t r a t e t h e s e r i e s . H i s i l l u s t r a t i o n s h a ve b e e n a h u g e f a c t o r i n N a n c y ’ s s u c c e s s . Th e y w e r e s o p h i s t i c a t e d a n d c l a s s y. Th e y b r o u g h t t o l i f e t h e c h a r a c t e r o f N a n c y ve r y m e m o r a b l y a n d n o d o u b t h e l p e d s a l e s a s c h i l d r e n we r e a t t r a c t e d t o t h e g l a m o r o u s c o ve r s . E a c h s u c c e e d i n g g e n e r a t i o n o f wo m e n a n d m e n w h o r e a d t h e b o o k s a s c h i l d r e n , h a ve p a s s e d t h e m d o wn t o s i b l i n g s , t o c h i l d r e n , t o g r a n d c h i l d r e n a n d h a ve k e p t a l i ve t h e m e m o r i e s o f r e a d i n g N a n c y a s a c h i l d . N o s t a l g i a p l a ys a l a r g e f a c t o r i n t h e c o n t i n u i n g s u c c e s s o f t h e s e r i e s , wh i c h i s s t i l l p u b l i s h e d t o d a y b y S i m o n & S c h u s t e r , wh o h e l p e d b r i n g N a n c y D r e w i n t o t h e m o d e r n e r a . Drew Source 2 Ewing, Jack. "Mildred A. Wirt." Guide To Literary Masters & Their Works (2007): 1. Literary Reference Center. Web. 23 Apr. 2014. Biography Mildred A. Wirt was born Mildred Augustine on July 10, 1905, in Ladora, Iowa. She began writing at an early age and published her first story at age fourteen. In 1925, after earning a B.A. in English at the State University of Iowa, she worked for a year as a reporter for a newspaper in Clinton, Iowa. The following year, she headed for New York City in search of a writing job. While writing work for women was scarce, she made a valuable contact who would soon provide the venue through which Wirt would become famous: Edward Stratemeyer, the owner of a syndicate that published a slew of popular juvenile fiction series. Returning home, Wirt in 1927 became the first woman to earn a master’s degree in journalism at the University of Iowa. Shortly thereafter, Stratemeyer invited her to write an entry in the syndicate’s Ruth Fielding series and Wirt accepted the challenge, producing her first novel, Ruth Fielding and Her Great Scenario (1927), under the pseudonym Alice B. Emerson. After writing several successful Fielding entries, she was offered the opportunity to write novels for a new series featuring a young female detective named Nancy Drew for a flat rate of $125 to $250, with no possibility of additional royalties. Under the syndicate-owned pseudonym Caroline Keene, Wirt wrote the first Nancy Drew mystery, The Secret of the Old Clock (1930); she eventually penned more than twenty entries in the series, concluding with The Clue of the Velvet Mask (1953). Under the same pseudonym, she also wrote a dozen novels in The Dana Girls Mystery Stories series between 1936 and 1954. In 1928, she married Asa Wirt, who worked for the Associated Press. The couple moved to Cleveland, Ohio, and later to Toledo, Ohio. Between the 1930’s and the early 1960’s, Wirt churned out nearly 140 juvenile and young adult novels under her own name and a variety of pseudonyms of her own or her syndicate’s invention, including Frank Bell, Don Palmer, Joan Clark, and Helen Louise Thorndyke. She contributed entries to many series of both the syndicate’s creation and her own, including Flash Evans, Penny Nichols, Doris Force, Honey Bunch, Penny Parker, and Dot and Dash. At the same time, Wirt wrote many stories and articles for publication in periodicals such as St. Nicholas Magazine and Calling All Girls. In 1944, Wirt began working as a reporter for the Toledo Times. In 1950, three years after her first husband died, she married the newspaper’s editor, George Benson, who died in 1959. By the mid-1960’s, Wirt had stopped writing fiction in favor of her full-time job as a court reporter. During that decade, she acquired her pilot’s license and wrote a number of aviation articles for various publications. When the Toledo Times folded in the 1970’s, Wirt went to work for the Toledo Blade, where she maintained a regular column virtually until her death. In 1993, Wirt was inducted into the Ohio Women’s Hall of Fame. In 1994, she was inducted into the Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame and received the University of Iowa Distinguished Alumni Award. Perhaps most significantly, in the 1990’s the current Nancy Drew franchise owners, publishers Simon and Shuster and Grosset and Dunlap, officially, legally, and publicly recognized her as the original Carolyn Keene. Vindicated at long last for her excellent fictional work, which has enthralled millions of children over the years, Wirt died on May 28, 2002, at age ninety-six. Drew Source 3 Pfluger, Jean. "The Mystery of Nancy Drew." University of North Texas. N.p., 1 Jan. 2003. Web. 23 Apr. 2014. <http://www.courses.unt.edu/efiga/HistoryAndEthnography/ 5960HistoryPaperJPfluger.doc.> For generations, serial novels like Nancy Drew have endured the adoration of young readers and the vexation of librarians and teachers. This paper looks at the growth of the serial novel through the 20 th century with emphasis on the Nancy Drew series. From their beginning, these books have drawn criticism for reasons that are discussed here along with recent research with an opposite view. Also in this paper, is a look into the specific appeal of Nancy Drew to several generations of readers. Nancy Drew ranks right at the top with Barbie as a favorite among girls and women of all ages. Since her beginning, she created a stir with readers, librarians, and teachers. The question I found myself asking was “why” on both sides. Why did my friends and I love these books and also why do my daughter and her friends continue to devour them with the same voraciousness that my generation did? If these books fill some need with their readers, why did librarians and teachers dislike them so much? Are the arguments of educator’s valid? Finding the answers to these questions may unlock the mystery of Nancy Drew. The Stratemeyer Syndicate, known as the “fiction factory”, under the guidance of Edward Stratemeyer produced more than 1000 stories in the early part of the 20th century. Stratemeyer created the “formula” book requirements including the basic characters and plotline. This formula required twenty-five chapters, each with a cliffhanger at the end, no kissing or touching, and no violence that could be upsetting. One interesting detail was that no character could be knocked unconscious more than once per book. He then paid authors to put the “flesh on the bones” (Plummer and Slania, 1988). Perhaps the most popular and certainly the most lasting series from Stratemeyer are the Nancy Drew mysteries. First written in 1930 by Mildred Wirt Benson under the pen name Carolyn Keene, Nancy Drew continues to attract young girls 73 years later. Mrs. Benson wrote the first 23 mysteries producing a new 200-page novel every six weeks. She created Nancy’s friend Bess with a persona of a slightly overweight coward, George as an athletic tomboy and the secretive, charming Ned as Nancy’s athletic boyfriend. Stratemeyer was not impressed with Ms. Benson’s first attempts at penning his creation as he felt Nancy was too “fresh and aggressive” (Nash, 2001). However, the publisher was pleased and so the first three books were published in 1930. Stratemeyer died a few weeks later leaving the empire to his daughter Harriet Stratemeyer Adams. Ms. Adams and her sister trimmed down the Syndicate but kept the biggest sellers, including Nancy Drew. The Depression brought financial problems and the sisters asked Ms. Benson to take a pay cut, which she refuse. Walter Karig wrote the next three books but he failed to honor the Syndicate request to keep his association with the books a secret. He told The Library of Congress of his authorship and they placed his name on their catalog cards, which infuriated the sisters into firing him and rehiring Ms. Benson. Ms. Benson continued as the principal ghostwriter for over 20 years. In 1959, Harriet Stratemeyer began rewriting the earlier books to bring Nancy into the next generation and eliminate racial stereotypes. “Villains lost their ethnic qualities and dialect-speaking character switched to Standard English, but the young sleuth herself stayed basically the same”(Contemporary Authors, 2000). The Stratemeyer sisters sold the syndicate to Simon & Schuster and in 1986 the publisher totally revamped the series launching the “Nancy Drew Files” and in 1994 the “Nancy Drew Notebooks”. “Nancy Drew on Campus” was published between 1995 and 1997 taking Nancy and her pals to college in a 25 book series. Nancy Drew’s long and prosperous career continues in publication today with millions of copies in many different languages. The first reviewers and librarians did not approve of the Stratemeyer formula and were very vocal about their views. As with the hated dime novels during the 19th century, librarians perceived in the series books sensationalism, lack of a true view of life, and their mass-market production made them unworthy of serious attention. The only serious attention these books were getting was negative. Katherine Sheldrick Ross (1995) states that in 1929, Mary E. S. Root prepared a list titled, “Not to be Circulated” in the Wilson Bulletin which included many of the Stratemeyer Syndicate books. At the same time, Lillian Herron Mitchell argued that librarians know that the best test of a children’s book was whether the literary minded adult enjoyed it or not. In Margaret Beckman’s article “Why Not the Bobbsey Twins” (1989), she stated that it would be a crime for a child to waste their childhood reading inferior work when there were other wonderful books available. Beckman went so far as to say that reading the Bobbsey Twins had a harmful effect on the minds of youth. Librarians complained that these books were without mental stimulation and would render young readers unable to develop sufficiently to read anything else. Critics also said that these books were too interesting, too sensational, that they presented an unrealistic view of life, and they reinforced stereotypes of race, gender, and class. In addition to the literary argument, many critics of this time held the position that when there were so few funds to buy books, they should be used to buy the interesting ones not worthless ones. It is apparent that librarians could find not one redeeming feature in these serial books. These views were held until the last few decades. As late as 1996 a coordinator of children’s services in San Francisco expressed, “We have never had Nancy Drew. They’re very obviously series books, with the same phrases repeated again and again. It’s lazy writing” (Associated Press, 1996). Nine-year-old Thea Bosselmann precipitated her statement when she went into a branch of the San Francisco public library and found that no branch in the system had Nancy Drew books. The coordinator went on to say, “ Money is placed into materials which meet children’s information needs, expands their multicultural awareness and experiences and which are of a higher literary quality”(San Francisco Chronicle, 1996). These are the same sentiments expressed 60 years earlier. Why then does Nancy Drew continue to be on the shelves of young girls rooms throughout the world? The number of copies sold over the last seven decades signals that there must be something to these stories. Researchers have looked into their enduring popularity and found many fans willing to share their stories. It seems that the reader’s view is totally different from those of the librarian. In 1997, Catherine Ross conducted a series of 142 interviews with individuals who labeled themselves dedicated readers. Of this group sixty percent reported having read serial novels, including Nancy Drew, as children. Ross’ study groups reported a strong background in reading. “The majority, though not all, mentioned at least some of the following events: they were read to by parents, grandparents, by siblings or by a special teacher or librarian; there were many books in their house and at least one other household member read for pleasure; they received books as gifts; they went to a library as a child; and in many cases they had taught themselves to read before entering school.” For these readers, serial novels were one of many positive, not negative, influences. Ross (1997) states that reading is more than just decoding sounds. Reading includes making sense of the marks on a page by understanding how stories work. When readingNancy Drew, the reader becomes familiar with the “how” which makes it easier to understand the plot and characters. The repetition so vilified by librarians in the 1930’s helps the reader to follow the plot, identify the hero and villain, and mentally combine a multitude of details into a whole. This study suggests that an important transition actually occurs for the reader while reading serial books, particularly for readers who have not had books read aloud to them. Through the highly patterned style of writing, the readers receive a clear introduction into the rules of reading. It is now recognized that attention should be paid to the phenomenon that occurs with serial books. Once a reader reads one, they go on to read more and more. One theory by Ross (1997) is that the series books minimize the risks of reading. Some interviewees told how making a decision as to what to read became suddenly easier when they found a series they loved such as Nancy Drew. Others expressed the guarantee of the unread book being as good as the previous that continued to draw them to series. For novice readers, serials provide the right balance between the known and the unknown, safety and adventure. Series detective stories make the process of simplifying and making sense of what is read obvious with detailed clues and the excitement of the detective when the clue is found. These clues teach the reader to pay attention for they unveil the mystery. From the book title, to the way the chapter titles highlight the plot element, to the grammar used, serial books provide a smooth avenue for young readers to move through in the deciphering of fictional literature. Reid and Cline (1997) also stated availability as one of the attractive features of serial books for readers. The young reader is not forced to move on to anything new until they are ready. Along with repetition and familiar texts as positive attributes, the books provide social benefits to the youth who read them. Sharing, talking about their favorite books is a fond memory of many Nancy Drew readers. I have witnessed this phenomenon among the girls in my school. Nancy Drew is very popular at this time with the 3rd, 4th, and 5th graders. They trade books, discuss them during breaks, and even keep lists of what they have read. This outbreak has prompted our library to buy a new set of the original series. It should ease the minds of librarians to know that readers of serial books do go on to other literature. Just as the simple formula is an attraction to readers at the time they are read, the same formula is what sends the readers on. Eventually, the appeal wears off once the reader can predict the ending too soon. Once it becomes too easy, successful readers move on. Child readers of Nancy Drew did not know they were mastering the intricate process of reading literature. They were blissfully unaware that they were learning the rules of reading through the clues and the solving of a mystery. Nor do they report being forever damaged by the simplicity of the stories. “When we listen to what readers say about series books, it seems as if they are talking about a totally different phenomenon from the mind-weakening experience described so confidently by the reading experts” (Ross, 1997). Readers loved the adventure, the mystery, the suspense of each of Nancy and her friend’s escapades. They love Nancy’s independent spirit and her blue roadster. Many girls, like the little girl in San Francisco, found their library did not carry the books, so they bought their own. Many readers remember their mother, sister, grandmother, or aunt as being the person to introduce them to the spirited heroine. Nancy Drew is the teenager many young girls long to be. “She is immaculate and self-possessed as a Miss America on tour. She is as cool as Mata Hari and as sweet as Betty Crocker. She plays parent to frightened children and victims of misfortune, allaying fears and inspiring rapturous confidence instantly with her soothing, reasonable voice. (Mason, 1975). Girls envy her confidence, wealth, independence, loving friends, and indulgent parent. She has no mother to tell her to behave like a lady; she has the unconditional love and support of her father, Carson Drew and housekeeper, Mrs. Hannah Green. She never goes to school, travels all over the world at the drop of a clue, and possesses a rapport with adults that anyone would envy. She has adoring friends, a handsome boyfriend, and that blue roadster. Most every reader mentions the blue roadster and the freedom and independence it allowed Nancy. Yet, most readers also talk about a respect for her seriousness. Nancy is humble, generous, and has high standards. “Many girls secretly entertain fantasies of rescuing people in need and making their lives happy—Nancy does it daily” (Kismaric & Heiferman, 1998). Beth Bales quotes one reader, “I was always struck by howNancy took the high road. There are lessons about integrity and character in her stories that need to re-examined today” (2002). She possesses endless courage, calm, and modesty. Hope Burwell personally remembers admiring Nancy’s innocence. She says, “My pantheon of female role models lacked neither intellect nor strength, but an example of a very particular kind of innocence.” She goes on to describe the character Nancy Drew as chaste, sincere and candid, driven only by the desire to “ do good”, yet intellectually capable of discerning which action is right action, and physically capable of carrying out her own missions (1995). She always desires to right wrong and can always take care of herself. “It was an innocence that somehow made her whole—the quality, I suspect, we were trying to get when we invented the word “wholesome” (Burwell, 1995). Along with her virtuous character, no one can argue that Nancy is not strong and courageous. She loves all sports playing great games of golf and tennis, she swims like an Olympic champion, fires a straight shot and can even scuba dive. She is an expert fisherman, can drive a bobsled and fly a plane. Her ability to handle her car is phenomenal as she avoids crashes and obstacles in every story. She is chased, pursued, sometimes cornered and never shows any fear or doubt of her ability to get out of a situation. She gave many of the first readers the signal that it was okay to be strong and courageous; a model acutely opposite of what society held up as acceptable, the quiet young lady who stood back and watched other’s accomplishments. One reader states that she admired most Nancy’s physical courage; despite that fact she thought Nancy was at times crazy (Reid-Walsh and Mitchell, 2001). Even today, in a society of strong women, Nancy still provides a model of strength, courage, and perseverance. However, it cannot be said that Nancy is a tomboy. “Nancy can whip up a dress or interpret a Chopin etude with subtle understanding” (Kismaric & Heiferman, 1998). Despite the fact she never seems to go to school, she knows something about everything. She always has the knowledge needed for any case using her photographic memory to describe a crook’s face to the cops perfectly. She learns on her own everything she needs to solve the mystery. In a world where women could not hope to have a career in medicine or law, Nancy pushes the limits and shows up the male characters she encounters. In today’s world where young girls realize there is a world of choices, Nancy Drew encourages them to “dream big and stay open to life’s possibilities” (Mason, 1995). As an avid Nancy Drew reader myself, since beginning this research I have asked myself what was it that drew me to devour these books. I can remember going to camp every summer and reading as many as I could in one week because the camp library had books that I didn’t have. I recently went through the list of titles and checked off twenty-one that seem familiar. Yet, it was while reading The Mystery of the 99 Steps with my daughter last month that I realized what it was that kept me reading. It was the adventure. I have often wondered where I acquired my “wanderlust” and realized that perhaps it was from Nancy Drew. She traveled all over the world, saw so many wonderful sights described in such detail that I felt like I was there too. Could it be that through these adventures, I developed a desire to travel the world and have my own adventures? It is probably not the only reason but it certainly could be a contributing factor. Now, I am able to live those adventures again with my own daughter. We have been to France and are on our way to Peru. I know Nancy will encounter obstacles, formulated “bad guys” and I know she will find every clue and solve the mystery. But, that doesn’t stop me from enjoying every word.