Designing STEM College Peer Mentoring Programs– A Quick Guide

advertisement

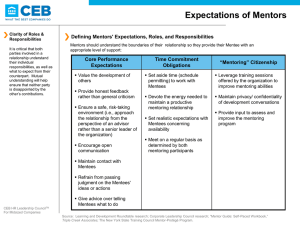

Designing STEM College Peer Mentoring Programs– A Quick Guide Becky Wai-Ling Packard, Ph.D. bpackard@mtholyoke.edu This document is divided into four components. Although I developed this resource as a guide for STEM peer mentoring at the college-level, much of the information can benefit program design across a range of ages and fields of study. Please refer to my website for updates throughout the semester. 1. Design Considerations a. What is your goal? b. Range of options for the goal(s) c. Tailoring based on budget and participants d. Training and assessment 2. Peer Mentoring Program Examples a. Peer-to-Peer- Same Level- Cohort/Teammate b. Peer-to-Peer- Same Level- Seasoned “Near-Peer” c. Peer-to-Peer- Step Ahead 3. Short Annotated Bibliography a. Articles on Peer Typologies, Selection, Training b. Supplementary Readings Packard STEM College Mentoring Quick Guide 1 Design Considerations Consideration 1: What is your goal? What type of mentoring makes sense? Define your goal for the program, or your ideal outcome. Is your goal recruitment, retention in school during a particular transition, or graduation in a particular major? Or increasing competitiveness of applicants to Ph.D. programs? Make sure that your mentoring program aligns with your goal such that you include mentoring functions likely to produce your desired outcomes. If the primary concern is raising performance in a gateway course, then emphasizing academic coaching and tutoring by peer mentors within that course would be ideal. If students are excelling in courses but eventually become disinterested in the major, then providing access to peer mentors within internships or other fieldbased opportunities would be more appropriate. This comment may seem obvious, but it seems that many mentoring programs are designed to emphasize peer socializing even when social support and belongingness may not be the primary outcome of interest. In other words, articulate your own definition of mentoring that will be used in your mentoring program. (See AAAS science mentoring website’s guidelines http://ehrweb.aaas.org/sciMentoring/research.php) Consideration 2: Consider options for meeting the goal, peer mentoring or otherwise Peer mentors are particularly adept at providing social support and a sense of belonging; facilitating the acquisition of academic skills or competencies; coaching through a particular process or transition by providing “inside knowledge” about a pathway. Thus, peer mentors make great coaches or tutors, if step-ahead or seasoned peers, or teammates if at the same level or in the same cohort. Consider how peer mentoring fits into the overall mentoring landscape in conjunction with faculty/supervisory mentoring which tends to provide better career support opportunities or increase competitiveness and interest for graduate school. (see Ensher et al., 2001; Kram & Isabella, 1985; Terrion & Leonard, 2007 for peer typologies and outcomes) Mentoring usually means interactive support over a period of time on a monthly if not weekly basis. Distributing information or sparking interest may not require a mentoring “program” per se, but peer mentors could be tapped for outreach through panels or demonstrations. (see Packard, 2003a; Shotton et al., 2007) Gateway courses or learning centers are logical places to integrate peer mentoring. Socializing is an important part of any mentoring program, but it is recommended to feature activities with an explicit academic or career focus such as coursework or research in some form where socializing can emerge as a natural byproduct of interaction. Most successful programs at the college-level pair academic/career goals with social goals. Contributing to one’s community and increasing competitiveness in one’s field are clear incentives for both mentors and mentees alike. (see Arrington et al., 2008; Shotton et al., 2007; Smith-Jentsch et al., 2008). A cadre of mentors (whether peer-same level, peer-seasoned, peer-step ahead, or supervisory) is recommended as multiple mentors provide access to different models and skill sets and increase support and retention of mentors—a double-win for a peer mentoring program. Even if pairing mentors and mentees into dyads, consider mixers for the entire community and allow mentors and mentees to meet up in their own groups on a regular basis. (see Packard, 2003a) Packard STEM College Mentoring Quick Guide 2 Consideration 3: Tailor based on budget and participants Logistics matter, whether looking at financial incentives, scheduling, and transportation. Do your research- don’t assume an opportunity is so good “anyone” would do it. You may miss out on the key folks you hope to reach. Gaining perspective on relative workloads (part-time work, school expectations) can help to design a program in which your target students can actually participate and thrive. It is better to have fewer mentors who are likely to follow through, as mentor commitment is linked to mentee satisfaction and other positive outcomes. Include training for mentors and mentees, including basic selection criteria, expectations for program, consequences for not meeting expectations, and resources to use when facing conflicts or difficulties. Goal-setting exercises at the start of the program for both parties can help facilitate dialogue about reasonable expectations with regard to which goals are likely to be met in the program, and thereby increasing commitment to meet goals that are possible, diminishing potential disappointments, and avoiding confusion. Having mentors and students show how they will integrate the program into their schedules is another useful mechanism for increasing commitment and follow-through. Anticipate the potential burden (face-to-face time, tracking, financial, paperwork) on the faculty/advisor sponsor such that the design sufficiently considers the support needed to keep the program running and support to parties involved. For example, the program coordinator may need assistance with the logistics of the program to make it feasible. (see Kasprisin et al., in press; Packard, 2003b) Consideration 4: Plan for assessment from the start Consider how you will baseline and track individuals over time, if desired. Do you have access to a contact person who will know the whereabouts of your participants after graduation? Make sure your assessments align with your objectives. Will you have access to the information you need to make your case for “effectiveness” at the end of the program (or a few years down the road)? For example, do you have access to grade reports? Include a variety of data sources. Focus groups tend to provide useful qualitative richness of experiences. Packard STEM College Mentoring Quick Guide 3 Peer mentoring definitions and examples 1. Peer Mentoring- Same-Level Peers support one another in a cohort, either supervised by an advisor, faculty member, or graduate student, usually focused on a research project or a transition into college program. Often, students enroll in courses or workshops with access to tutors. Peer mentoring in these programs, however, usually described in terms of the peers within the team or cohort. The goal is to solidify relationships among entering (often underrepresented) students. Likely outcomes- social support, positive affect toward field-relevant activities, retention, increased academic skills if peer-to-peer academic study groups emphasized. Certain LSAMP programs take this form, such as Summer Bridge programs, where a cohort of incoming college students arrives early to the university for coursework and mentoring. Alternatively, a program can focus on the academic year, developing cohorts of students, typically featuring residential groupings in the same dorm (Residential Academic Programs), enrolling in a common seminar, co-scheduling of sections of courses, or fixed study groups within a section of a course. Summer Bridge examples: University of Maryland (http://www.umes.edu/amp/) UC-Berkeley (http://summerbridge.berkeley.edu/info.html) UC-Riverside (http://www.summerbridge.ucr.edu/) Residential Academic Program example: Umass-Amherst - http://www.umass.edu/rap/declared_majors.htm Packard STEM College Mentoring Quick Guide 4 2. Peer Mentoring- Near-Peer or Seasoned Peer with relevant experience in a particular domain provides support to peers at the same level, meaning they are both in the same college (e.g., usually advanced students mentoring incoming students, but can just be one semester ahead). This typically takes place in a class in which the peer mentor already took and excelled, and the peer mentor acts as a teaching assistant, tutor, or study group leader within the class or outside of class. The peer mentor may also act as a peer leader, or “liaison”, providing coaching and advising to newer students, as part of a leadership circle, cadre, or student leader organization. Likely outcomes: higher grades and persistence in class, social support, greater knowledge about steps needed to advance in the major or extra-curricular options. Even when the programs pair mentors with mentees, there are usually activities for the whole community. A team of mentors is recommended- at least two peer mentors so they have support from each other and collectively can provide multiple models to their peers. When housed in the student resource center, peer mentors can hold “office hours” and then are not assigned to any one student. Typically there is a faculty sponsor. Club Format, Pairing Incoming with Advanced Students Examples: Carnegie Mellon big sisters/little sisters within computer science http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~women/initiatives/bigsister.shtml Texas A & M University – peer mentors for newer female students in computer science http://awics.cs.tamu.edu/mentoring.php Moraine Valley Community College—Connects incoming women students in computer technology to experienced women students and professionals. The web “showcasing” of multiple mentors is especially notable. http://www.morainevalley.edu/cad/nsfmentors.htm University of Michigan- pairs incoming engineering students with advanced students http://www.engin.umich.edu/students/advising/mentoring/index.html University of Nebraska-Lincoln- peer mentors for computer science/engineering students http://cse.unl.edu/gpsti/PDFs/MentoringCenter.pdf Depaul University- College of computing, digital media- pairing first years with advanced http://www.cdm.depaul.edu/studentlife/Pages/UndergraduatePeerMentoring.aspx Packard STEM College Mentoring Quick Guide 5 Course-Based, Peer Tutoring Examples: University of Woolgong—Peer-Assisted Study Sessions http://www.uow.edu.au/student/services/pass New Mexico State – Peer Tutoring in Gateway Computer Science Courses with good notes on mentor training and what did not work http://www.cs.nmsu.edu/~mmartin/pubs/SETE_2004.pdf Packard STEM College Mentoring Quick Guide 6 3. Step-Ahead Peer Mentoring Peer is a step-ahead in schooling, so for example, college students mentoring high school students, or four-year college students mentoring community college students. The peer mentors have relevant experience in a particular domain, and they may engage in joint projects, discussion sessions, or tutoring in classes. Step-ahead mentors can provide greater role modeling and career support than seasoned peers as they are further ahead in the pathway, but logistically there can be different issues to facilitate regular contact. Likely outcomes: higher grades and persistence in classes, social support, greater knowledge about steps needed to advance in the major or extra-curricular options, role modeling, scaffolding in research or related career support. Step-ahead programs have developed out of student leadership organizations or science scholars programs, providing a cadre of student leaders that can be tapped to provide outreach to high school students. Not all programs have regular contact with high school students, thus the result may be a pool of peer mentors but not necessarily a peer mentoring program per se. College community service learning courses offer opportunities to partner with high school students in a course or after-school program. Linking mentors to course requirements or participation in the leadership program increases success whereas purely volunteer-based programs are not as likely to see the same follow through. Examples: “Leadership” or “Scholars” Cadre model Lamar University: Computer science program for women and minorities, good example of selection criteria and expectations http://www.cs.lamar.edu/inspire/Content/INSPIREDOnePageSp08.pdf Towson University: COSMIC S-Stem Scholars program emphasizes link between computer science and math http://www.towson.edu/cosmic/ Iowa State Women in Science and Engineering’s Student Role Models program, includes a list of 61 prepared activities for K-12 with a brief description K-12 http://www.pwse.iastate.edu/PDF/rolemodelactivities.pdf Lousiana State University- Isaiah Warner’s national model funded by HHMI, peer mentors take courses for increased effectiveness, need to maintain eligibility http://appl003.lsu.edu/acadaff/hhmippweb.nsf/$Content/Success?OpenDocument Example of Community Service Learning course: Umass Lowell - Holly Yanco’s program where college students and high school students work together in an 8-week program intregrating technology and art. http://artbotics.cs.uml.edu/index.php?n=Programs.Fall2007AfterSchoolProgram Packard STEM College Mentoring Quick Guide 7 Short Annotated Bibliography Although many STEM peer mentoring programs exist, few research articles have been published on the topic, or the peer mentoring component is embedded into a larger mentoring framework making it more challenging to find. This bibliography includes a few core pieces about peer mentoring and a few targeting mentoring and STEM mentoring in general. Feel free to contact me for suggestions about further reading. Arrington, C. A., Hill, J. B., Radfar, R., Whisnant, D. M., & Bass, C. G. (2008). Peer mentoring in the general chemistry and organic chemistry laboratories. The Pinacol rearrangement: An exercise in NMR and IR spectroscopy for general chemistry and organic chemistry laboratories. Journal of Chemical Education, 85(2), 288-290. Peer mentors drawn from organic chemistry course teach organic chemistry lab for general chemistry students to increase understanding and interest in organic chemistry. Ensher, E. A., Thomas, C., & Murphy, S. E. (2001). Comparison of traditional, step-ahead, and peer mentoring on proteges’ support, satisfaction, and perceptions of career success: A social exchange perspective. Journal of Business & Psychology, 15, 419-438. Contrasts different types of mentors. Illustrates the usefulness of peer mentors for social support and effectiveness of traditional supervisory mentors for career support. Stepahead peers can (modestly) provide modest both career and social mentoring. Kasprisin, C. A., Single, P. B., Single, R. M., Muller, C. B., & Ferrier, J. L. (in press). Improved mentor satisfaction: Emphasizing protege training for adult-age mentoring dyads. Mentoring & Tutoring. Reviews training in mentoring programs with a focus on MentorNet program. Using an experimental design, the study documents benefits of protégé training. Much previous research solely focuses on mentor training. Kram, K. E., & Isabella, L. A. (1985). The role of peer relationships in career development. The Academy of Management Journal, 28(1), 110-132. Foundational piece that introduces the notion of peers (categorized as information peer, collegial peer, and special peer) providing mentoring functions in psychosocial and career domains (such as sharing information, providing emotional support) that can be complementary to those provided by supervisors (sponsorship, role modeling). Packard, B. W. (2003a). Web-based mentoring: Challenging traditional models to increase women’s access. Mentoring & Tutoring, 11(1), 53-65. Provides a useful review of literature of curricular and extra-curricular, face-to-face and technology-supported mentoring programs designed to increase women’s participation in STEM fields. Argues for alternatives for traditional mentors to gain relevant functions. Packard, B. W. (2003b). Student training promotes mentoring awareness and action. Career Development Quarterly, 51, 335-345. Describes a program used to help women, minorities, and first generation college students in STEM fields to set goals for mentoring and to identify multiple mentors. Packard STEM College Mentoring Quick Guide 8 Shotton, H. J., Oosahwe, E. S. L., & Cintron, R. (2007). Stories of success: Experiences of American Indian students in a peer-mentoring retention program. The Review of Higher Education, 31(1), 81-107. Used focus groups to analyze a peer mentoring program targeting academic and social transitions of incoming and transfer American Indian students. Peer mentors met with mentees in weekly study hall meetings. Identified core elements of the mentoring relationships that predicted success including mentor commitment and ability to relate. Illustrates the power of successful matches and the precarious nature of matching. Seymour, E., Hunter, A., Laursen, S. L., & Deantoni, T. (2004). Establishing the benefits of research experiences for undergraduates in the sciences: First findings from a threeyear study. Science Education, 88, 493-534. Study illustrates the many benefits of undergraduate research experiences for networking, learning and persistence in the field. Smith-Jentsch, K. A., Scielzo, S. A., Yarbrough, C. S., & Rosopa, P. J. (2008). A comparison of face-to-face and electronic peer-mentoring: Interactions with mentor gender. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72, 193-206. Female electronic mentors (college seniors) assigned to first year students in an introductory biology class provided just as much psychosocial and career support as face-to-face female mentors, whereas male mentors in the electronic condition reduced dialogue, with reduced effectiveness. Terrion, J. L., & Leonard, D. (2007). A taxonomy of the characteristics of student peer mentors in higher education: Findings from a literature review. Mentoring & Tutoring, 15(2), 149-164. This is an excellent synthesis of literature on peer mentoring, focused on only face-toface mentoring. Key elements for selecting mentors (e.g., ability to commit, same program of study, empathy, communication skills, flexibility) are discussed at length. Supplementary Readings: I recommend any articles written by Jean Rhodes as she studied the importance of long-term mentoring relationships, and detrimental outcomes for relationships that end prematurely, and ways to screen potential participants. Even though she does not focus on STEM, and instead focuses on youth mentoring programs such as Big-Brother Big-Sister, her work provides a rich foundation for all mentoring researchers. http://psych.umb.edu/faculty/rhodes/publications/recent.html AAAS has a science mentoring research website in development. Mentoring resources including publications from AWIS and HHMI are available here. http://ehrweb.aaas.org/sciMentoring/resources.php Packard STEM College Mentoring Quick Guide 9