ชื่อเรื่องภาษาไทย (Angsana New 16 pt, bold)

advertisement

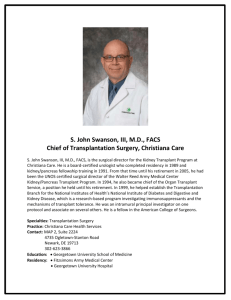

PHARMACEUTICAL CARE IN LIVER TRANSPLANT OUTPATIENT CLINIC AT SIRIRAJ HOSPITAL Pornpen Leuvittawat1,*, Suvatna Chulavatnatol1,#, Thida Ningsananda2 and Yongyut Sirivatanauksorn3 1 Department of Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Mahidol University, Bangkok 10400 Thailand 2 The Association of Hospital Pharmacy (Thailand), Bangkok 10110 Thailand 3 Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok 10700 Thailand *e-mail: pornpen.leu@mahidol.ac.th, #e-mail: suvatna.chu@mahidol.ac.th Abstract Liver transplantation (LT) is the most effective treatment for patients with end stage liver disease (ESLD). Liver transplant patients are usually having risk for drug therapy problems (DTPs) because of poly-pharmacy, involving immunosuppressants, anti-infective agents and other medications for their underlying diseases. The present study, therefore, aimed to identify and resolve DTPs after LT through clinical pharmacy service. A total of 75 patients in Liver Transplant Outpatient Clinic at Siriraj Hospital who were ≥ 18 years of age and were able to communicate with pharmacist were recruited. Research pharmacist assessed for DTPs and provided interventions in the 1st visit and monitored for intervention outcomes and provided counseling to patients in the 2nd visit. Fifty-six DTPs were identified in 28 patients in the 1st visit (2.00±1.19 DTPs/patient), while 26 DTPs were identified in 19 patients in the 2nd visit (1.37±0.83 DTPs/patient. “Noncompliance” was the major DTPs found in the study, 62.50% and 65.38% at the 1st visit and the 2nd visit, respectively. The second rank of DTPs were “unnecessary drug therapy” (10.71%) and “dosage too high” (10.71%) in the 1st visit and “need additional drug therapy” (15.38%) in the 2nd visit. A total of 82 pharmacist interventions were provided. Most of them could decrease “unnecessary drug therapy”, “dosage too low” and “dosage too high” problems. For “noncompliance”, it might need more intensive pharmaceutical care process to decrease such problem. The physicians’ acceptance rates for the interventions were 65%-80% whereas 100% acceptance rate was achieved from patients. In conclusion, pharmaceutical care had been shown to have beneficial effects for liver transplant patients particularly in the reduction of some DTPs. However, “noncompliance” was still a major DTP which might need intensive pharmaceutical care process to overcome. Keywords: Pharmaceutical care, Pharmacy service, Liver transplant patients Introduction Liver transplantation (LT) is the most effective treatment for patients with end stage liver disease (ESLD). In Thailand, the number of LT patients was increased to 0.95 per million populations in 2010 (1), and Thai Transplantation Society has reported that 360 Thai patients are treated with LT, currently (2). After LT, patients have to receive immunosuppressive therapy to prevent hepatic allograft rejection as maintenance immunosuppression phase for their whole life. Such long-term use of these agents are usually associated with various side effects leading to many complications including renal disorders, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease and others (3-5). As a result, LT patients are usually exposed to the risk of drug therapy problems (DTPs) because of poly-pharmacy involving immunosuppressants, anti-infective agents and other drugs for their underlying diseases (6-9). Pharmaceutical care, i.e., resolving of preventable DTPs had been studied in various groups of transplant patients including kidney transplantation (9), lung transplantation (6) and heart transplantation (10). However, no studies about DTPs have been reported for LT. Therefore, the present study aimed to identify and resolve DTPs after LT through clinical pharmacy service in Liver Transplant Outpatient Clinic at Siriraj Hospital. Methodology A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted in Liver Transplant Outpatient Clinic at Siriraj Hospital from May 2011 through May 2012. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by Siriraj Institutional Review Board (SIRB), Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University. LT patients who were 18 years of age and older, had willing to sign informed consent and were able to communicate with pharmacist were recruited to the study. Seven days before the 1st visit, research pharmacist reviewed patient’s demographic and prescription data from out-patient department (OPD) card and medication chart of Liver Transplant Clinic. At the visit, research pharmacist interviewed patient to detect DTPs which were identified and classified into 7 categories according to Cipolle and colleagues (11). For patient with DTPs, research pharmacist provided an appropriate intervention to correct and prevent DTPs and recorded in OPD card. Moreover, knowledge of immunosuppressants including indication, potential drug or herb interactions and adverse drug reactions were provided to patient. After visiting a physician, patient’s prescription was verified by research pharmacist for detecting DTPs. If DTPs occurred, research pharmacist would resolve the problems by suggesting intervention and discussing with physician. For the 2nd visit, research pharmacist monitored treatment using patient interview and pill count techniques and provided counseling to patient. In both visits, the acceptance rate of interventions was evaluated by physicians and patients. Descriptive statistics (the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 13.0) were used to describe patient’s demographic data including gender, number of medication used per patient, number of comorbidity, number of categorized DTPs, number of intervention and acceptance rate. Incidence of DTPs was also reported as number of patient with DTP/ number of all studied patients, presented as percentage. Results Seventy-five patients were recruited in the 1st visit and 71 patients were followed in the 2nd visit. Two patients lost to follow-up and two rejected to participate in the 2nd visit. Most of the studied patients were males (61.3%). Mean±SD of age was 54.69±11.31 years, number of medication used per patient was 7.72±3.85 items and number of comorbidities per one patient was 3.24±1.96 diseases. Post-LT patients with mean time post LT of more than 3 months were 97.4% of total patients. Three major causes of LT were hepatitis B virus (33.3%), hepatitis C virus (29.3%) and hepatocellular carcinoma (25.4%). At the 1st visit, 28 patients had at least one DTP. Fifty-six DTPs were found in total and 2.00±1.19 (mean±SD) DTPs were found per one patient. At the 2nd visit, DTPs were identified in 19 of 71 patients in 26 items (1.37±0.83 DTPs/patient). As a result, incidence of DTPs was accounted for 37.33% and 26.76% in the 1st visit and the 2nd visit, respectively. Categories of DTPs found at both visits are displayed in Table 1. In both visits, the DTPs mostly identified were “noncompliance”, 35 DTPs (62.50%) at the 1st visit and 17 DTPs (65.38%) at the 2nd visit. The second rank of DTPs category of the 1st visit was “unnecessary drug therapy” (10.71%) and “dosage too high” (10.71%) while that of the 2nd visit was “need additional drug therapy” (15.38%). Research pharmacist provided 82 interventions in total, 52 were to patients whereas 30 were to physicians. Most of interventions were counseling in order to improve compliance of patients. The remaining interventions included cessation of medication, decrease dose, addition of drug and increase dose as shown in Table 2. Fifty-six recommendations were provided in the 1st visit while 26 recommendations were provided in the 2nd visit. The physician acceptance rates were 65% and 80% in the 1st visit and the 2nd visit, respectively whereas 100% of interventions to patients were accepted in both visits. Top three groups of medications that caused high percentages of DTPs were immunosuppressants, antihypertensive drugs and anti-dyslipidemic drugs as displayed in Figure 1. Table 1 Number and category of DTPs during study period DTPs Category Unnecessary drug therapy Need additional drug therapy Dosage too low Adverse drug reaction Dosage too high Noncompliance Total Number of DTPs (%) 1st visit 6 (10.71) 4 (7.15) 3 (5.36) 2 (3.57) 6 (10.71) 35 (62.50) 56 (100) 2nd visit 1 (3.85) 4 (15.38) 1 (3.85) 1 (3.85) 2 (7.69) 17 (65.38) 26 (100) Table 2 Number and category of pharmacist’s intervention during study period Number of Intervention (%) Intervention 1st visit 2nd visit Counseling to patients 36 (64.28) 16 (61.54) Cessation of drug 9 (16.07) 3 (11.54) Addition of drug 4 (7.14) 4 (15.38) Decrease dose 5 (8.94) 2 (7.69) Increase dose 2 (3.57) 1 (3.85) Total 56 (100) 26 (100) 35 Pe rcentage of DTPs 30 25 20 Visit1 15 Visit2 10 5 0 IMP ARV FUN DIA HTN DYS VIT GAS HEP RES ANA URO Medication group Figure 1 Percentage of DTPs from various medication groups IMP = immunosuppressants, ARV = anti-retroviral drugs, FUN = anti-fungal agents, ATB = anti-bacterial drugs, DIA = anti-diabetic agents, HTN = anti-hypertensive agents, DYS = anti-dyslipidemic agents, VIT = vitamin, GAS = drugs used in gastro-intestinal disorders, HEP = drugs used in hepatic disorders, RES = drugs used in respiratory system disorders, ANA = analgesic and antipyretics, URO = drugs used in genito-urinary disorders. Discussion and Conclusion The incidence of DTPs was decreased after pharmaceutical care was provided (37.33% vs 26.76%, in the 1st visit and the 2nd visit, respectively). These findings implied that pharmacist participation could help physician to identify and resolve DTPs. This result agreed with other studies. Harrison, et al pointed that pharmacist could identify and resolve DTPs in higher proportion in pharmacist consulted visit (1.05±1.34 DTPs per visit), than in standard visit which there was no pharmacist consultation (0.51±0.64 DTP per visit) (6). In addition, pharmacy service also helped physician to reduce drug related problems, i.e., 55 pharmacist interventions could resolve drug related problems of 37 kidney transplant patients (9). These outcomes pointed that pharmacist activity had beneficial effects in transplant patients. Three categories of DTPs were reduced after pharmaceutical care was provided. These included “unnecessary drug therapy”, “dosage too low” and “dosage too high”. In contrast, for “noncompliance” which was the major DTPs in our study, the occurrence was slightly increased in the 2nd visit. Such result was also happened with “need additional drug therapy” and “adverse drug reaction” problems. It seemed that pharmacist interventions were quite successful when there were unnecessary drug therapy problems or inappropriate doses of the drugs. Duplication of medication from several physicians, for instance, duplication of angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), duplication of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, duplication of calcium carbonate, and duplication of opioids were the most frequent problems of unnecessary drug therapy. In these cases, physicians usually accepted when research pharmacist suggested to delete unnecessary drug from the regimen. For “dosage too low” and “dosage too high”, most of pharmacist interventions were adjustment to the appropriate dose of such medications particularly anti-hypertensive agents, anti-diabetic drugs and immunosuppressants. However, pharmacist interventions could not decrease the problems of “need additional drug therapy” (7.15% and 15.38% in the 1st visit and the 2nd visit, respectively) and “adverse drug reaction” (slightly increased from 3.57% in the 1st visit to 3.85% in the 2nd visit). It has been found that after long-term use of immunosuppressant, patients are more likely to have risks for hypertension and dyslipidemia. For example, hypertension was increased in 29% of total patients at 3-month post LT after using of calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) (12) whereas hypertriglyceridemia was found within 1-12 months after CNIs and sirolimus use (13). For our cases, these complications were also presented but physician might consider that the conditions still could be initially controlled by life style modification instead of adding some medications as suggested by research pharmacist. Therefore, they mostly did not accept the interventions for “need additional drug therapy” problem. For “adverse drug reaction”, the problem was slightly increased in the 2nd visit, which was only 1 DTP and it was unpredictable ADR thus it was difficult to manage. More focus should be put on “noncompliance” which was the major DTPs found in high percentages in both visits of our study. Major causes of this problem were patients’ forgetfulness, omission of medication or patient took wrong dose or dose frequency because they did not understand physician’s order for medication administration. In these cases, research pharmacist provided counseling, i.e., emphasizing on indication of drug, dosage regimen and risk of noncompliance. Adequate labeling and written information of medication use were also provided. However, these methods seemed to be inadequate for increasing patient’s compliance. Chisholm, et al (14) proposed that intensive and continuous compliance enhancement strategy should be provided. In their study, they provided patient counseling every month for one year by face to face or telephone counseling, and monitored for target immunosuppressant level. As a result, they could increase compliance rate to 96% in pharmacist intervention’s group compared to 82% in group without pharmacist intervention (14). In addition, Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS), which is the electronic monitoring device used to assess patient’s adherence from time and date when patient opens and closes bottle to take medication (15), is also reported to be more effective tool to increase patient’s compliance. Thus, it seemed that more intensive pharmaceutical care should be performed in order to decrease “noncompliance” problem. In conclusion, DTPs were common in LT patients. Pharmaceutical care to identify and resolve DTPs had been shown to have beneficial effect for these patients in the reduction of some DTPs. However, more intensive pharmaceutical care intervention might be needed for “noncompliance” problem. References 1. Kim WR, Stock PG, Smith JM, Heimbach JK, Skeans MA, Edwards EB, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2011 Annual Data Report: liver. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(Suppl 1):73-102. 2. Thai Transplantation Society. [cited 2013, July 4 ]; Available from: http://www.transplantthai.org/en/about.php?news id=00001. 3. Mukherjee S, Mukherjee U. A comprehensive review of immunosupprssion used for liver transplantation. J Transplant. 2009:1-20. 4. Pillai AA, Levitsky J. Overview of immunosuppression in liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(34):4225-33. 5. Taylor AJ, Watson CJ, Bradley JA. Immunosuppressive agents in solid organ transplantation: Mechanisms of action and therapeutic efficacy. Crit Rev Oncol Hemat. 2005;56:23-46. 6. Harrison JJ, Wang J, Cervenko J, Jackson L, Munyal D, Hamandi B, et al. Pilot study of a pharmaceutical care intervention in an outpatient lung transplant clinic. Clin Transplant. 2012;26:E149-57. 7. Klein A, Otto G, Kramer I. Impact of a pharmaceutical care program on liver transplant patients' compliance with immunosuppressive medication: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial using electronic monitoring. Transplantation. 2009;87:839-47. 8. Prot-Labarthe S, Therrien R, Demanche C, Larocque D, Bussieres JF. Pharmaceutical care in an inpatient pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant service. J Oncol Pharm Practice. 2008;14:147-52. 9. Wang HY, Chan ALF, Chen MT, Liao CH, Tian YF. Effects of pharmaceutical care intervention by clinical pharmacists in renal transplant clinics. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:2319-23. 10. Martin JH, Hernandez MM, Noguera IF, Moral LD, Sanjuan VM, Andres JL. Assessment of a reconciliation and information programme for heart transplant patients. Farm Hosp. 2010;34(1):1-8. 11. Cipolle RJ, Strand LM, Morley PC. Pharmaceutical care practice: The clinician's guide. 2nd ed. New York: McGaw-Hill; 2004. 12. Jain A, Reyes J, Kashyap R, Rohal S, Abu-Elmagd K, Starzl T, et al. What have we learned about primary liver transplantation under tacrolimus immunosuppression? Long-term follow-up of the first 1000 patients. Ann Surg. 1999;230:441-8. 13. Watt KD, Charlton MR. Metabolic syndrome and liver transplantation: A review and guide to management. J Hepatol. 2010;53:199-206. 14. Chisholm MA, Mulloy LL, Jagadeesan M, DiPiro JT. Impact of clinical pharmacy services on renal transplant patients' compliance with immunosuppressive medications. Clin Transplant. 2001;15:330-6. 15. Morrissey PE, Flynn ML, Lin S. Medication noncompliance and its implications in transplant recipients. Drugs. 2007;67(10):1463-81. Acknowledgements: The authors would like to express our appreciation to Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University for partially support for the research grant. Contribution from liver transplantation teams including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and all patients are also appreciated.