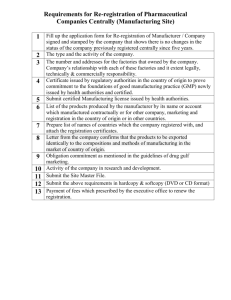

Costanzo obligation

advertisement