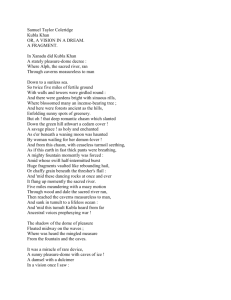

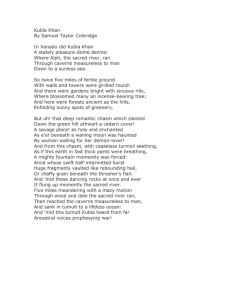

Kubla composition opium fragment

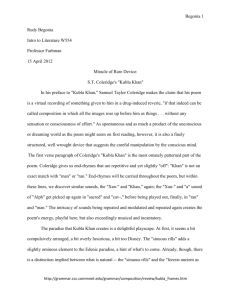

advertisement