The King can do no Wrong - Sally A. Roberts Law Firm

advertisement

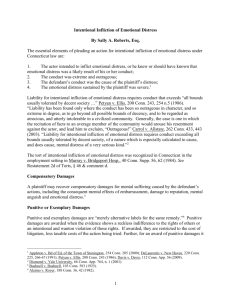

Doctrine of Sovereign Immunity The King can do no Wrong1 Connecticut, has long recognized the validity of the common-law principle that the state cannot be sued without its consent and that since the state can act only through its officers and agents a suit against a state officer is in effect one against the sovereign state.2 This rule had its origin in the ancient common law, predicated on the principle that the king, being the fountainhead of justice, could not be sued in his own courts.3 While the principle of sovereign immunity is deeply rooted in our common law, it has, nevertheless, been modified and adapted to the American concept of constitutional government where the source of governmental power and authority is not vested by divine right in a ruler but rests in the people themselves who have adopted constitutions creating governments with defined and limited powers and courts to interpret these basic laws.4 The source of the sovereign power of the state is now the constitution which created it, and it is now recognized that, as Mr. Justice Holmes wrote: “A sovereign is exempt from suit, not because of any formal conception or obsolete theory, but on the logical and practical ground that there can be no legal right as against the authority that makes the law on which the right depends.”5 The practical and logical basis of the doctrine is today recognized to rest on this principle and on the hazard “that the subjection of the state and federal governments to private litigation might constitute a serious interference with the performance of their functions and with their control over their respective instrumentalities, funds, and property.”6 Sovereign immunity does not protect state officials from suits to recover property taken or held in violation of the constitution or without statutory authority, even though the property is held in the name of the state of Connecticut. State officials cannot therefore shield themselves with sovereign immunity if a party alleges and proves that they took or retained his real property in a manner which was either unconstitutional or unauthorized by statute.7 The common-law principle is that the State cannot be sued without its consent. Because the State can act only through its officers and agents, a suit against a State officer concerning a matter in which the officer represents the State is, in effect, against the State. Therefore, the Connecticut Supreme Court has dealt with such suits as if they were solely against the State and 1 Latin phrase, Rex non potest peccare. Horton v. Meskill, 172 Conn. 615, 623 (1977). 3 1 Pollack & Maitland, History of English Law (2d Ed.) pp. 514-18. 4 Horton v. Meskill, 172 Conn. 615, 623 (1977). 5 Kawananakoa v. Polyblank, 205 U.S. 349, 353 (1907). 6 59 Harv. L. Rev. 1060, 1061. 7 Horton v. Meskill, 172 Conn. 615, 625 (1977). 2 has referred to the State as the defendant.8 The doctrine of sovereign immunity implicates subject matter jurisdiction and is therefore a basis for granting a motion to dismiss.9 Although the doctrine of sovereign immunity has been modified by statute and precedent, the Connecticut Supreme Court has declined to permit monetary awards against the State of Connecticut or its officials in the absence of a statute granting such authority. When sovereign immunity has not been waived, the Claims Commissioner is authorized by statute to hear monetary claims against the State and determine whether the claimant has a cognizable claim. Conn. Gen. Stat. §§ 4-141 through 4-165b. The commissioner, if he deems it “just and equitable,” may sanction suit against the State on any claim which, in his opinion, presents an issue of law or fact under which the State, if it is a private person, can be liable. Conn. Gen. Stat. § 4-160(a).10 8 Fetterman v. University of Connecticut, 192 Conn. 539, 550-51 (1984). Kelly v. Univ. of Conn. Health Ctr., 290 Conn. 245 (2009). 10 Lagassey v. State, 268 Conn. 723 (2004). 9