COM 3XX: Interpersonal Communication Theory

advertisement

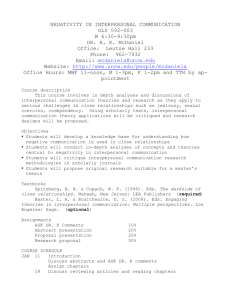

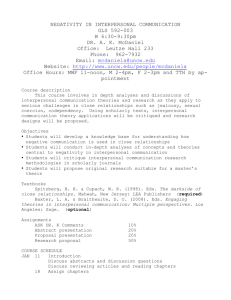

Interpersonal Communication Theory (HCOM 570-01) Spring 2009, Mondays – 4:00 to 6:50 p.m., DeMille Hall 156 Instructor: Office Address: Office Phone: Office Hours: E-mail: Class Webpage: Text/Readings: Dr. Jennifer Bevan (call me Jen!) Moulton Center 248 (inside Communication Studies Dept. Office in MC241) (714) 532-7768 M: 2:15-3:45 pm; T: 12:15-12:45 pm & 2:15-3:15 pm; TH: 11:45-12:45 pm; & by appt. bevan@chapman.edu - you have the highest chance of reaching me via email www.chapman.edu/blackboard (click on the “Logging in to Blackboard” link if you have trouble logging in) 1. Required texts (2): - Baxter, L. A., & Braithwaite, D. O. (Eds.). (2008). Engaging theories in interpersonal communication: Multiple perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. - Miller, K. (2005). Communication theories: Perspectives, processes, and contexts (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw Hill. These books are primarily intended to provide background and basic concepts, ideas and critiques related to interpersonal communication theories – they will not be my primary sources of class lecture materials. 2. Required readings (see list in Tentative Schedule): Available as PDF or Word files on BlackBoard under “Course Documents” heading. Most of the substantive readings for the course will be found here and are chapters in scholarly books and journal articles that are either empirical research studies or reviews. Nature and Goals of the Course: This course is designed to give you a working map of important theories in interpersonal communication. It would an impossible task to teach you all the theories that exist in and about interpersonal communication in the fullest depth in one semester. Instead, the course offers pointers and teaches you to consume theory, and in so doing, it surveys major theoretical issues and propositions in interpersonal communication, particularly as they relate to health and strategic communication. The course begins with consideration of the ways in which theories are constructed and have been broadly applied to human communication and then moves on to consider specific theories about particular interpersonal communication activities and enterprises. As you read through the materials that are offered for your consideration, keep asking yourself: (1) Why is this important? (2) What would count as evidence? (3) How would evidence be gathered? (4) What are the underlying assumptions about the nature of the human being? (4) What values and implications lie below the surface statements made here? (5) What is not articulated in the theory that in fact is important to explicate? Don't despair that there is a lot to read: be satisfied with an acquisition of two things: a) a broad atlas of kinds of theory (don’t even attempt to believe that you will know everything about all these theories by the end of this course); and 2) a general compass of questions and issues to guide you through the theoretical landscape. The course is designed to give you the chance to acquire these things and provide a basis for later growth and development of more detail and complexity. At the end of the semester, I hope that you will be able to do the following: Describe the concerns of theory and theoretical scholarly research in the study of interpersonal communication; Define and cogently discuss theory especially in relation to interpersonal communication; Accurately outline the process of creating, developing, and testing theories of interpersonal communication; Recognize and identify the defining characteristics of scientific theoretical approaches to the study of interpersonal communication; Apply interpersonal communication concepts and principles to the understanding of health and/or strategic communication; and Successfully use the language of communication theory in speaking and writing. Note: It is extremely unlikely that you will find all of these theories equally appealing. You are encouraged to develop your own perspective on theory, on interpersonal communication, and on the special topics that we shall cover during the course. Use this class as an opportunity not only to become familiar with the theories that are out there but also to adopt or try out a particular approach that you might find useful in your future work in this program and beyond. Class Conduct and Expectations: In order to create and maintain a supportive communication environment, I ask the following of you: 1. You must refrain from side-conversations, reading non-related materials, and doing anything else that might make it difficult to hear/pay attention to others in the class. 2. NO CELL-PHONES, PDAs, MP3s, or anything else that would cause distractions will be permitted in class (please turn your phones/PDAs off or leave them elsewhere when in class). 3. I heavily discourage coming late to class or leaving class early. This type of behavior is rude and disturbing to me and to your fellow classmates, especially in a small seminar class environment such as this. 4. You are here by your choice. I expect this class to be as important to you as your other obligations. When possible, I do not let outside obligations burden my participation in this course; I expect you to do the same. If that is not possible, you should drop the course. 5. Because this is a graduate course, I also expect that you will be prepared to actively participate in class discussions when you come to class – this means that you have read and critically evaluated the assigned readings before class and are ready to insightfully engage the material and each other. Our goal each week is move toward a shared understanding of the material and the broader topic. 6. You may use laptops in class ONLY for taking class notes. If I find that you are spending time online or are working on other things, I will ban laptops in class. 7. Late papers are not acceptable in this course and will be severely penalized unless permission for extended deadlines is obtained beforehand (and deadlines will only be extended for emergencies and with proper written documentation). If, at any point, you are confused about assignments, expectations, or feel you are getting lost in the course material, please set up a time to meet with me. Ethics: Chapman University is a community of scholars that emphasizes the mutual responsibility of all members to seek knowledge honestly and in good faith. Students are responsible for doing their own work, and academic dishonesty of any kind will be subject to a range of sanctions by the instructor and referral to the university’s Academic Integrity Committee, which may impose additional sanctions up to and including dismissal. Using the ideas or words of another person, even a peer, or a Web site, as if it were your own, is plagiarism. See the Graduate Catalog (http://www.chapman.edu/catalog/oc/2007-2008/gr/) for the full policy. I take this policy extremely seriously and do not consider your being uninformed about what plagiarism is and is not to be an acceptable or justifiable excuse! Students with Disabilities: If you have a documented disability and are in need of alternate class accommodations, you are invited to meet with me as soon in the semester as possible to discuss your needs. Please also contact the Center for Academic Success (130 Cecil B. DeMille Hall, cas@chapman.edu, 714-997-6828) to register and coordinate arrangements for accommodations and services. BlackBoard: BlackBoard is an essential way for me to disseminate information about the course to you. For example, I use BlackBoard to provide required readings and exam information, post grades, etc. Please look under “Course Documents” and/or “Course Information” for these documents. Please note: You are REQUIRED to log on to BlackBoard in this course and I expect that you will check it at least the morning of each class meeting. If there is a change in the class (cancellation, due date or topic changes, etc.), email through BlackBoard will be the primary source for my dissemination of this information to you. It is thus your responsibility to check the email address that is linked to your BlackBoard account (which is your chapman.edu email account unless you change it) daily – I will not send you emails any other way except via BlackBoard. Not checking your email account frequently is not an excuse for missing important class information disseminated via BlackBoard email. Grades (including final course grades) will ONLY be posted on BlackBoard and will not be given via email due to security concerns. Evaluation: Your grade will be determined in four (4) ways: 1. Class Participation/Activities (15%) is essential in a seminar class such as this. As a general guide, a superior class participant is thoroughly familiar with assigned readings, makes frequent contributions to class discussions, and shows keen insight into the material. An above average class participant demonstrates familiarity with assigned readings and makes regular and substantive contributions. An average class participant reads the assigned material and occasionally makes substantive contributions. In addition to regular class participation, we will also be actively grappling with theoretical issues in class – I will ask you to engage in debates, provide written answers to questions for discussion, and consider specific issues throughout the semester, and your participation in each of these activities will contribute to this portion of your overall course grade. This is partially done (with little prior notice but with class time to work) to ensure that you are prepared for class each week as well as to assist you in understanding and directly engaging in the material. I expect that you will prepare for class by being able to do two important things (at a minimum!) when participating in each class (and I will be asking these questions in class each week): (1) Critique the theory we are covering according to the five criteria discussed in Chapter 3 of the Miller text and in class during Week 3; and (2) Identify the specific theoretical propositions or concepts that are tested by an assigned research study, the related study findings, and what these findings mean for the theory. Excessive absences (which, for a graduate course, is missing more than one class meeting) will result in your inability to contribute to in-class group discussions and will be taken into account in this portion of the class grade as well. 2. Exams (2 @ 20% of course grade each = 40% total) will be take home, open book essay exams with questions that ask you to evaluate concepts and theories and consider them in the broader contexts of health/strategic communication. The final exam is not cumulative. 3. Weekly Papers (20%) are 1-2 page papers (double spaced) that help you organize your thoughts about, or communicate your reactions to (e.g., confusion, excitement, anger), the week’s readings. These papers could represent reactions, extensions, rants, raves, critiques, questions, ideas, and so on and can be in memo form if you wish. A required part of each paper is a section titled “What I Would Like to Talk About This Week…” I will use these ideas in planning for each class session. Therefore, weekly papers are due to me by 5 p.m. the day before class (beginning Sunday, 2/8) via email to bevan@chapman.edu (I will reply to confirm receipt). I expect that these papers will help you prepare your class participation and I will evaluate them based upon how much you demonstrate understanding of the theories and the specific readings – identifying and briefly discussing trends or concepts across readings will be particularly helpful. They are also important because they help me determine what to expect from you in each class. 4. Theory Description/Evaluation/Application Research Paper and Presentation (20% paper and 5% presentation = 25% total): For this final, culminating assignment, you will select a theory (it can be a theory that we cover in class or any theory discussed in either the Miller or Baxter & Braithwaite texts that is of interest to you) and do three things: (1) thoroughly describe the theory and review research that has been conducted using this theory as a framework – at least four pieces of original research NOT already assigned as readings in this course must be included and discussed in terms of the theory you select (these research pieces do not all have to be in communication journals or specifically about health and/or strategic communication); (2) using these research findings and other general writings about the theory (including class readings), thoroughly evaluate/critique the theory’s usefulness using the criteria from Chapter 3 of the Miller text that was discussed in class in Week 3; and (3) taking your critique into account, apply your theory to a specific, practical aspect of health or strategic communication that is of interest to you. To accomplish this third part, I envision the paper including (1) a description of the applied area you’ll be looking at (e.g., patient provider interaction, family counseling, etc.), (2) a thorough consideration of the “fit” between the theory and the area, with attention paid to how the theory could contribute to improvements in practice, and (3) a consideration of areas in which the theory falls short in providing workable solutions to the practice area. In other words, how can the theory be successfully applied to enhance knowledge about an actual health or strategic communication situation? What can the theory do to improve this particular context or situation? If you wish, you may focus on a particular campaign or series of messages when completing this portion of the paper. In essence, provide a specific, detailed example of how an interpersonal communication theory can be usefully melded with the typically atheoretical study of health or strategic communication. These papers will be 15-18 pages of text in length, will include a title and reference page, and will conform to APA 5th ed. style (as will all writing done in this course). As your perspective and interpretation is an essential component of this paper, you may only directly quote sparingly (i.e., approximately once per page of text). We will hold individual meetings to discuss your ideas and chart your progress on this paper during class time on April 13. Plan to have a theory or two in mind by this date so our meeting can be as productive as possible. I will read drafts of this paper and provide substantive comments (a partial or full draft is acceptable) if received by 7:00 p.m. on Friday, May 15 (I HIGHLY recommend submitting a draft to me). The paper is due via email by 7:00 p.m. on Friday, May 22. In addition, you will informally present your paper (focusing on the critique and application portions) for approximately 15-20 minutes during our class dinner as a “work in progress” on May 11. Grading Disputes: You are welcome to come in during office hours or at another pre-arranged time and review any of your exam/paper results or your grade in the course. Although I do not anticipate any problems, it is possible that we may disagree on a particular grade. I am open to discussion about grades; however, there are some guidelines that are to be followed for such discussions to take place. First, grades are not discussed in the classroom. Second, grades will not be discussed unless you provide me with your written viewpoint before our meeting. Third, I will only consider individual written grade change requests for one week after each grade is posted on BlackBoard. Don’t wait until the last week of class to review your test results! Grade Distribution: A AB+ B BC+ 93%-100% 90%-92% 87%-89% 83%-86% 80%-82% 77%-79% C 73%-76% C- 70%-72% D+ 67%-69% D 63%-66% D- 60%-62% F 0%-59% Tentative Schedule Note: Readings and activities must be completed by the dates they are assigned. I reserve the right to change the schedule as needed. February 2 (Week 1): Intro/Communication Theory Background B & B, Chap. 1 Miller, Chap. 1 Berger, C. R. (2005). Interpersonal communication: Theoretical perspectives, future prospects. Journal of Communication, 55, 415-447. Craig, R. T. (1999). Communication theory as a field. Communication Theory, 9, 119-161. **Note: Mostly skim Craig (it is quite a dense piece – don’t worry if you don’t understand some of it!) but do closely read the Sketch of the Field and Working the Field sections for an excellent description of the different perspectives in our discipline. Powers, J. H. (1995). On the intellectual structure of the human communication discipline. Communication Education, 44, 191-222. February 9 (Week 2): “Classic” Theoretical Debates in Communication **Note: Read articles in the following order… Debate 1: Motley, M. T. (1990). On whether one can(not) not communicate: An examination via traditional communication postulates. Western Journal of Speech Communication, 54, 1-20. Beavin Bavelas, J. (1990). Behaving and communicating: A reply to Motley. Western Journal of Speech Communication, 54, 593-602. Debate 2: Berger, C. R. (1991). Communication theories and other curios. Communication Monographs, 58, 101-113. Burleson, B. R. (1992). Taking communication seriously. Communication Monographs, 59, 79-86. Proctor II, R. F. (1992). Preserving the tie that binds: A response to Berger’s essay. Communication Monographs, 59, 98-100. Berger, C. R. (1992). Curiouser and curiouser curios. Communication Monographs, 59, 101-107. February 16 (Week 3): Theory: What It Is, How to Evaluate It, and How It Links to Health Communication Miller, Chaps. 2 & 3 Fishbein, M., & Yzer, M. C. (2003). Using theory to design effective health behavior interventions. Communication Theory, 13, 164-183. Parrott, R. (2004). Emphasizing “communication” in health communication. Journal of Communication, 54, 752-787. Witte, K. (1998). Theory-based interventions and evaluations of outreach efforts. White Paper for National Network of Libraries of Medicine. Found at the following web address: http://nnlm.gov/evaluation/pub/witte/ February 23 (Week 4): Constructivism (readings continued on the next page) **Note: Read articles in the following order… B & B, Chap. 4 Miller, pp. 104-111 Burleson, B. R. (2003). Emotional support skill. In J. O Greene & B. R. Burleson (Eds.), Handbook of communication and social interaction skills (pp. 551-594). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Woods, E. (1998). Communication abilities as predictors of verbal and nonverbal performance in persuasive interaction. Communication Reports, 11, 167-178. Samter, W. (2002). How gender and cognitive complexity influence the provision of social support: A study of indirect effects. Communication Reports, 15, 5-16. Kline, S. L., & Ceropski, J. M. (1984). Person-centered communication in medical practice. In G. M. Phillips & J. T. Wood, Emergent issues in human decision making (pp. 120-141). Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. Koesten, J., & Anderson, K. (2004). Exploring the influence of family communication patterns, cognitive complexity, and interpersonal competence on adolescent risk behaviors. The Journal of Family Communication, 4, 99-121. March 2 (Week 5): Expectancy Violation and Interaction Adaptation Theories **Note: Read articles in the following order… B & B, Chap. 14 Miller, pp. 158-164 Burgoon, J. K., & Jones, S. B. (1976). Toward a theory of personal space expectations and their violations. Human Communication Research, 2, 131-146. Burgoon, J. K., & Hale, J. L. (1988). Nonverbal expectancy violations: Model elaboration and application to immediacy behaviors. Communication Monographs, 55, 58-79. Burgoon, J. K. (1993). Interpersonal expectations, expectation violations, and emotional communication. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 12, 30-48. Bevan, J. L. (2003). Expectancy violation theory and sexual resistance in close, cross-sex relationships. Communication Monographs, 70, 68-82. Miczo, N., Allspach, L. E., & Burgoon, J. K. (1999). Converging on the phenomenon of interpersonal adaptation: Interaction adaptation theory. In L. K. Guerrero, J. A. DeVito, & M. L. Hecht (Eds.), The nonverbal communication reader (pp. 462-471). Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland. Duggan, A. P., & Bradshaw, Y. S. (2008). Mutual influence processes in physician-patient communication: An interaction adaptation perspective. Communication Research Reports, 25, 211-226. March 9 (Week 6): Theory Debate: Uncertainty Reduction vs. Predicted Outcome Value **Note: Read articles in the following order… B & B, Chap. 10 Miller, pp. 175-183 Berger, C. R., & Calabrese, R. J. (1975). Some explorations in initial interaction and beyond: Toward a developmental theory of interpersonal communication. Human Communication Research, 1, 99-112. Sunnafrank, M. (1986a). Predicted outcome value during initial interactions: A reformulation of uncertainty reduction theory. Human Communication Research, 13, 3-33. Berger, C. R. (1986). Uncertain outcome values in predicted relationships: Uncertainty reduction theory then and now. Human Communication Research, 13, 34-38. Sunnafrank, M. (1986b). Predicted outcome values: Just now and then? Human Communication Research, 13, 3940. Sunnafrank, M. (1990). Predicted outcome value and uncertainty reduction theories: A test of competing perspectives. Human Communication Research, 17, 76-103. Grove, T. G., & Werkman, D. L. (1991). Conversations with able-bodied and visibly disabled strangers: An adversarial test of predicted outcome value and uncertainty reduction theories. Human Communication Research, 17, 507-534. March 16 (Week 7): Recent Theories about Uncertainty (readings cont. on following page) We will hold class from 3:30-6:15 this week for a videoconference with Dr. Walid Afifi **Note: Read articles in the following order… B & B, Chap. 9 Miller, pp. 137-142 Bradac, J. J. (2001). Theory comparison: Uncertainty reduction, problematic integration, uncertainty management, and other curious constructs. Journal of Communication, 51, 456-476. Brashers, D. E., Neidig, J. L., Haas, S. M., Dobbs, L. K., Cardillo, L. W., Russell, J. A. (2000). Communication in the management of uncertainty: The case of persons living with HIV or AIDS. Communication Monographs, 67, 63-84. Thompson, S., & O’Hair, H. D. (2008). Advice-giving and the management of uncertainty for cancer survivors. Health Communication, 23, 340-348. Afifi, W. A., & Weiner, J. L. (2004). Toward a theory of motivated information management. Communication Theory, 14, 167-190. Afifi, W. A., & Weiner, J. L. (2006). Seeking information about sexual health: Applying the theory of motivated information management. Human Communication Research, 32, 35-57. March 23 (Week 8): Midterm Distributed March 30 (Week 9): Facework/Politeness and Communication Privacy Management Theories **Note: Read articles in the following order… B & B, Chaps. 15 & 19 Miller, pp. 299-303 Cupach, W. R., & Metts, S. (1994). Facework. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Chapter 1, pp. 1-16. Caplan, S. E., & Samter, W. (1999). The role of facework in younger and older adults’ evaluations of social support messages. Communication Quarterly, 47, 245-264. Tracy, K., & Tracy, S. J. (1998). Rudeness at 911: Reconceptualizing face and face attack. Human Communication Research, 25, 225-251. B & B, Chap. 23 Petronio, S. (2002). Boundaries of privacy: Dialectics of disclosure. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. Chapter 1, pp. 1-35. Petronio, S. (2004). Road to developing communication privacy management theory: Narrative in progress, please stand by. Journal of Family Communication, 4, 193-207. Durham, W. T. (2008). The rules-based process of revealing/concealing the family planning decisions of voluntarily child-free couples: A communication privacy management perspective. Communication Studies, 59, 132-147. April 6 (Week 10): Spring Break April 13 (Week 11): Final Paper Meetings/Work on Final Paper April 20 (Week 12): A Sampling of Theories of Interpersonal Control, Goals, and Influence **Note: Read articles in the following order… B & B, Chap. 5 Dillard, J. P., Segrin, C., & Harden, J. M. (1989). Primary and secondary goals in the production of interpersonal influence messages. Communication Monographs, 56, 19-38. Miller, pp. 127-129 Greene, K., Parrott, R., & Serovich, J. M. (1993). Privacy, HIV testing, and AIDS: College students’ versus parents’ perspectives. Health Communication, 5, 59-74. Robinson, J. D., Raup-Kriger, J. L., Burke, G., Weber, V., & Oesterling, B. (2008). The relative influence of patients’ pre-visit global satisfaction with medical care on patients’ post-visit satisfaction with physicians’ communication. Communication Research Reports, 25, 1-9. LePoire, B. A., & Dailey, R. M. (2006). Inconsistent nurturing as control theory: A new theory in family communication. In D. O. Braithwaite & L. A. Baxter (Eds.), Engaging theories in family communication: Multiple perspectives (pp. 82-98). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. LePoire, B. A., Hallett, J. S., & Erlandson, K. T. (2000). An initial test of inconsistent nurturing as control theory: How partners of drug abusers assist their partners’ sobriety. Human Communication Research, 26, 432-457. April 27 (Week 13): The Battle over the Elaboration Likelihood Model **Note: Read articles in the following order… Miller, pp. 129-133 Booth-Butterfield, S., & Welbourne, J. (2002). The Elaboration Likelihood Model: Its impact on persuasion theory and research. In J. P. Dillard & M. Pfau (Eds.), The persuasion handbook: Developments in theory and practice (pp. 155-173). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Todorov, A., Chaiken, S., & Henderson, M. D. (2002). The Heuristic-Systematic Model of social information processing. In J. P. Dillard & M. Pfau (Eds.), The persuasion handbook: Developments in theory and practice (pp. 195-211). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Stiff, J. B. (1986). Cognitive processing of persuasive message cues: A meta-analytic review of the effects of supporting information on attitudes. Communication Monographs, 53, 75-89. Petty, R. E., Kasmer, J. A., Haugtvedt, C. P., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1987). Source and message factors in persuasion: A reply to Stiff’s critique of the elaboration likelihood model. Communication Monographs, 54, 233-249. Stiff, J. B., & Boster, F. J. (1987). Cognitive processing: Additional thoughts and a reply to Petty, Kasmer, Haugtvedt, and Cacioppo. Communication Monographs, 54, 250-256. Petty, R. E., Cacioppo, J. T., Kasmer, J. A., Haugtvedt, C. P. (1987). A reply to Stiff and Boster. Communication Monographs, 54, 257-263. Smith, S. W., Massi Lindsey, L. L., Kopfman, J. E., Yoo, J., & Morrison, K. (2008). Predictors of engaging in family discussion about organ donations and getting organ donor cards witnessed. Health Communication, 23, 142-152. May 4 (Week 14): Theory of Reasoned Action/Theory of Planned Behavior (From an Interpersonal Perspective) **Note: Read articles in the following order… Miller, pp. 126-127 Hale, J. L., Householder, B. J., & Greene, K. L. (2002). The theory of reasoned action. In J. P. Dillard & M. Pfau (Eds.), The persuasion handbook: Developments in theory and practice (pp. 259-286). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Greene, K., Hale, J. L., & Rubin, D. L. (1997). A test of the theory of reasoned action in the context of condom use and AIDS. Communication Reports, 10, 21-33. Connor, M., Graham, S., & Moore, B. (1999). Alcohol and intentions to use condoms: Applying the theory of planned behavior. Psychology and Health, 14, 795-812. Stephenson, M. T., Quick, B. L., Atkinson, J., & Tschida, D. A. (2005). Authoritative parenting and drug-prevention practices: Implications for antidrug ads for parents. Health Communication, 17, 301-321. Bresnahan, M., Lee, S. Y., Smith, S. W., Shearman, S., Nebashi, R., Park, C. Y., & Yoo, J. (2007). A theory of planned behavior study of college students’ intention to register as organ donors in Japan, Korea, and the United States. Health Communication, 21, 201-211. May 11 (Week 15): Final Paper “Work In Progress” Presentations/Group Dinner at Rutabegorz Final exam distributed at the end of class May 18: Final exam due by 7:00 p.m. via email to bevan@chapman.edu May 22 (F): Theory research paper due by 7:00 p.m. via email to bevan@chapman.edu