LECTURE ABOUT LISTENING

advertisement

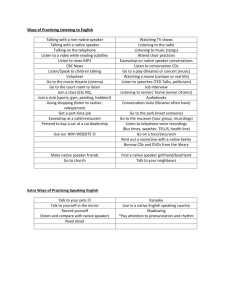

TAKING CLASSROOM NOTES Contact Margie Wildblood School Twenty-first Century Scholars Support Site, Indiana University Kokomo Phone 765-455-9573 Mwildblood@ssaci.state.in.us or mwildblo@iuk.edu Email GRADE LEVEL(S) 7th Grade and above STUDENT INDICATOR(S) Students will develop effective strategies for recording and studying classroom notes. TIME REQUIRED 30-40 minutes MATERIALS NEEDED Power Point Presentation: Taking and Studying Classroom Notes Handouts: Power Point Slides Word Documents: Janet’s Study Notes Lecture About Listening Blank notebook paper (one page per student) ACTIVITY SUMMARY Students will view a Power Point presentation detailing strategies for taking and studying effective classroom notes. Students will practice taking notes and answer questions based on their notes. PROCEDURE EVALUATION: How will you know what percentage of the students have mastered the identified guidance indicators? CITATION(S) You may include copyrighted materials in “materials needed,” but do not reproduce copyrighted materials in your lesson plan. Noncopyrighted materials should be included in your lesson plan and cited here. PART ONE: Title and Objectives. Explain to students that forgetting begins almost immediately. Taking good notes will help them remember what they have heard and help them study more effectively. Slide 1. PART TWO: Review the first 3 hints for taking classroom notes. Slides 2-4. PART THREE: Distribute copies of “Janet’s Study Notes.” Explain how to take notes, using the handout for illustration. Slides 5-10. PART FOUR: Review general hints for taking notes. Slides 11-14. PART FIVE: Explain how to use classroom notes to study for tests. Slides 15-17. PART SIX: Distribute blank notebook paper to each student. Read Lecture About Listening, writing key ideas (as listed in “Lecture” key box) on board as these are recited. Instruct students to use the hints discussed when taking notes on the lecture. PART SEVEN: Ask students to write answers to 4 questions about the Lecture on flip side of notepaper. Slide 18 Students will demonstrate mastery by correctly answering 3 of 4 questions about a lecture. Doing Well in College By John Langan and Judith Nadell McGraw-Hill, Inc. 1980 JANET’S STUDY NOTES* Business 101 2-7-02 Origin of ec ec = economic(s) res = resource Economics – from Greek words meaning “HOUSE” and “TO MANAGE”. Meaning gradually extended to cover not only management of household but of business and governments Def of ec Ec (definition) – STUDY OF HOW SCARCE RESOURCES ARE ALLOCATED IN A SOCIETY OF UNLIMITED WANTS. Every society provides goods + services; these are available in limited quantities and so have value. One of most imp. Assumptions of ec: Though res of world are limited, wants of people are not. This means an ec system can never produce enough to satisfy everyone completely. Def of ec res 2 types of ec res 2 types of property res + defs Ec res – all factors that go into production of goods + services. Two types: 1. PROPERTY RES – 2 kinds: a. LAND – all natural res (land, timber, water, oil, minerals) b. CAPITAL – all the machinery, tools, equipment, + building needed to produce goods + distribute them to consumers 2. HUMAN RESOURCES – 3 kinds a. LABOR – all physical and mental talents needed to produce goods + services b. MANAGERIAL ABILITY – talent needed to 3 kinds of human res + def bring together land, capital, + labor to produce goods and services c. TECHNOLOGY – accumulated fund of knowledge which helps in production of Goods + services *Excerpted from p. 31, Doing Well in College, by John Langan and Judith Nadell, McGraw-Hill, 1980 INSTRUCTIONS TO STUDENTS: “This activity will give you practice in taking lecture notes. The activity is based on a short lecture on listening given in a speech class. Take notes on the lecture as I read it aloud. As you take your notes, apply the hints you learned in our discussion.” INSTRUCTIONS TO LECTURER: (Items that the original lecturer put on the board are shown in the box below. Write these on the board as you come to them in the lecture.) On Board: Problem of losing attention 125 WPM = talking speed 500 WPM = listening speed spare time three techniques for concentration intend to listen After reading the “Lecture About Listening,” ask students to answer the following questions by referring to their notes. Review the correct responses. Poll students (as a group) to determine how many answered 3 or more questions correctly. Questions on the Lecture: 1. What is a listening problem that many people have? 2. What are common talking and listening speeds? 3. What are three techniques to help you pay attention when someone else is talking? 4. What is the most important step you can take to become a better listener? LECTURE ABOUT LISTENING* I’m going to describe to you a listening problem that many people have. I’ll also explain why many people have the problem, and I’ll tell you what can be done about the problem. The listening problem that many people have is that they lose attention while listening to a speaker. They get bored, their minds wander, their thoughts go elsewhere. Everyone has had this experience of losing attention, but probably few people understand one of the main reasons why we have this trouble keeping our attention on the speaker. The reason is this: There is a great deal of difference between talking speed and listening speed. The average speaker talks at the rate of 125 words a minute. On the other hand, we can listen and think at the rate of about 500 words a minute. Picture it: The speaker is going along at 125 WPM and we are sitting there ready to move at four times that speed. The speaker is like a tortoise plodding along slowly; we, the listeners, are like the rabbit ready to dash along at a much faster speed. The result of this gap is that we have a lot of spare time to use while listening to a speech. Unfortunately many of us use this time to go off on side excursions of our own. We may begin thinking about a date, a sports event, a new shirt we want to buy, balancing our budget, how to start saving money, what we must do later in the day, and a thousand other things. The result of the side excursions may be that, when our attention returns to the speaker, we find that we have been left far behind. The speaker has gotten into some new idea, and we, having missed some connection, have little sense of what is being talked about. We may have to listen very closely for five minutes to get back on track. The temptation at this point is to go back to our own special world of thoughts and forget about the speaker. Then we’re wasting both our time and the speaker’s time. What we must do, instead, is work hard to keep our attention on the speaker and to concentrate on what is being said. Here are three mental techniques you can use to keep your concentration on the speaker. First of all, summarize what the speaker has said. Do this after each new point is developed. This constant summarizing will help you pay attention. Second, try to guess where the speaker is going next. Try to anticipate what direction the speaker is going to take, based on what has already been said. This game you play with yourself arouses your curiosity and helps maintain your attention. Third, question the truth, validity, of the speaker’s words. Compare the points made with your own knowledge and experience. Keep trying to decide whether you agree or disagree with the speaker on the basis of what you know. Don’t simply take as gospel whatever the speaker tells you; question it—ask yourself whether you think it is true. Remember, then, to summarize what the speaker has said, try to guess where the speaker is going next, and question the truth of what is stated. All these techniques can make you a better listener. But even better than these three techniques, I think, is that you make a conscious effort to listen more closely. You must intend to concentrate, intend to listen carefully. For example, you should go into your classes every day determined to pay close attention. It should be easier for you to make this important mental decision if you remember how easily attention can wander when someone else is speaking. *Taken from pp. 35-36, Doing Well in College, John Langan and Judith Nadell, McGraw-Hill, 1980