Open Access version via Utrecht University Repository

advertisement

Research project

Prevalence of obesity and associated ‘feeding

characteristics’ as risk factor for obesity in cats in

Palmerston North.

Drs. C.A.M. Metekohy

0248614

Faculteit Diergeneeskunde

Universiteit Utrecht

25 mei 2009

‘Research project’ drs. C.A.M. Metekohy

Studentnr: 0248614

1

“Prevalence of obesity and associated ‘Feeding Characteristics’

as risk factor for obesity in cats in Palmerston North”

Abstract

This study was conducted to identify feeding variables as risk factors for obesity in cats.

Besides it could give an indication if prevalence of obesity in cats is increasing just as in

humans and if this is due to a change in feeding characteristics or a change in environmental

and management variables.

A door-to-door survey was conducted within the city limits of Palmerston North and obtained

data on the environment, health, behaviour and diet of 200 cats. The interviewers used a

validated scoring system to assess the body condition of each cat and this was converted in a

dichotomous dependent variable. The variables were grouped into four risk-factor groupings

for stepwise logistic regression; cat characteristics, owner’s perception of their cat, household

characteristics and feeding variables. From the feeding variables only feeding dry food was

identified as a risk factor for obesity. All significant variables from each group (p < 0.05)

were included in a combined model and assessed to control for confounding. In this model the

feeding variables weren’t significant. This study didn’t support the hypothesis that the

prevalence of obesity in the cat population of Palmerston North has increased, neither that this

was caused by feeding variables.

Since feeding characteristics were not identified as a risk factor for obesity, the accent of

weight control programs should not lie in changing cats’ feeding pattern or food types, but

adapted according other identified risk factors. However a lot of these factors, like age, gender

and neuterstatus, are difficult to influence. Dietary management is one of the easiest and a

practical method to adjust energy intake at critical times during a cat’s life, where a change in

circumstances may result in a greater risk of developing obesity. So adjustments to feeding

variables can prevent weight gain.

2

‘Research project’ drs. C.A.M. Metekohy

Studentnr: 0248614

3

“Prevalence of obesity and associated ‘Feeding Characteristics’

as risk factor for obesity in cats in Palmerston North”

1.

Introduction

Obesity is a common nutritional disorder of cats in the veterinary practice. The prevalence of

obese and overweight cats reported in earlier studies ranges from 18,9% to 52% in different

countries. (Sloth 1992, Scarlett 1994, Robertson 1999, Allan 2000, Russell 2000, Lund 2005, Colliard 2008) In humans an

increase in prevalence of obesity is seen and it is assumed that there might be a similar

increase in cats. (German A.J. 2006)

Obesity is defined as an accumulation of excessive amounts of adipose tissue in the body.

(Burkholder 2000)

This results from excessive dietary energy intake or insufficient energy

utilization, which causes a positive energy balance for an extended period of time. (Burkholder

2000)

Excessive deposition of fat has detrimental effects on health and longevity. Obesity in cats is

associated with several clinical conditions such as lameness, diabetes mellitus (Rand 2004), heat

intolerance, decreased reproductive efficiency, and non-allergic skin problems. (Scarlett et al

1994,1998)

Besides this some authors revealed a predisposition for feline lower urinary tract

diseases, oral diseases, neoplasia, hepatic lipidosis, decreased immune function, and a

shortened lifespan in obese cats, (Sloth 1992, Robertson 1999, Russell 2000, Lund 2005, German 2006) although not

all of these associations between obesity and the clinical effects are well documented or are

not consistent in every study. (Jaso-Friedman 2007)

Recent research has suggested a mechanism for the link between excessive amounts of

adipose tissue and many diseases. Adipose tissue has a regulatory role and can produce and

secrete several hormones en cytokines. A major concern are the mildly elevated

concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines, like TNFα and Interleukin-6 seen in

overweight cats. This persistent low-grade inflammation secondary to obesity is thought to

play a causal role in chronic diseases and inflammations, like Diabetes Mellitus. (Miller 1998,

Coppack 2001, Laflamme 2006)

Obesity is also a risk factor for surgical and anaesthetic complications, due to problems with

estimated anaesthetic dose, catheter placement and prolonged operating time.

Overall, obesity makes clinical evaluation more difficult, like physical examination, thoracic

auscultation, palpation and aspiration of peripheral lymphnodes, abdominal palpation, blood

sampling, cystocentesis and diagnostic imaging. (German 2006)

There are several methods for assessing obesity in cats. Butterwick (2000) developed a

method to predict body fat content in cats, the Feline Body Mass Index, using two physical

measurements: the ribcage and the Leg Index measurement (LIM). All measurements should

be made with the cat in a standing position with the legs perpendicular to the ground and the

head in an upright position. ‘Ribcage’ is the circumference in cm at the point of the 9th cranial

rib and the ‘LIM’ is the distance between the patella and the calcaneal tuber of the left

posterior limb measured in cm.

Body fat % = {[(Ribcage/0.7076)-LIM/0.9156}-LIM

The use of these physical measurements can overcome individual differences in physique

between individual cats and between cats of different breeds, because there is limited

information on optimal weights for pure-bred cats and none for cross-bred cats.

Cats with a percentage of body fat content of less than 30% and above 10% are considered to

be normal weight or non-obese, based on clinical experience of the authors.

Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) has been developed for the evaluation of bone

mineral status in humans, but has come into use for determining body fat and lean body mass

and can be used for body composition measurements in dogs and cats. (Munday 1994) However,

while DEXA is an excellent research tool, it may not be practical for use in veterinary practice

due to equipment cost. Just like other research techniques used to determine body

composition, like Chemical analysis, densitometry, total body water measurement,

4

‘Research project’ drs. C.A.M. Metekohy

Studentnr: 0248614

ultrasonography, electral conductance and advanced imaging techniques, due to their costs,

ease of use, acceptance, and invasiveness.

Body Condition Score (BCS) systems provide a semi-quantitative assessment of the body

condition. There are five, six, seven (S.H.A.P.E. system) (German 2006) and nine point systems in

use for cats. (Laflamme 1997) All systems assess visual and palpable characteristics that correlate

subcutaneous fat, abdominal fat and superficial musculature.

Numerous factors may predispose an individual animal to obesity. Besides the mismatch

between energy intake and energy expenditure, which is the main reason for the development

of obesity, some diseases and pharmaceuticals can cause obesity. One can think of

hypothyroidism (Scott-Moncrieff 2007), with a decreased metabolic rate and hypercorticism (Chiaramonte

2007)

, glucocorticoids therapy and anticonvulsants drugs (benzodiazepines, phenobarbitone)

which induce polyphagia. (Fidin Repertorium 2009, Sloth 1992, German 2006)

There are also individual differences in metabolic rate and energy expenditure, which

predispose certain animals for the development of obesity. (Sloth 1992, Hill 2006) Over the years

there have been several studies to identify the risk factors for the development of obesity.

Genetic effect has been demonstrated by authors who found a association between certain

breeds and obesity. (Sloth 1992, Robertson 1999, Lund 2005)

Risk factors demonstrated in most of the studies are being male, being neutered and middle

aged. These are all cat-characteristics. The various studies can not come to an agreement

concerning feeding variables and environmental influences. Potential risk factors found in

these studies are feeding premium (brands that are purchased in a veterinary practice, pet

store, or large- format pet retailer) and therapeutic foods (sold at veterinary clinics and

prescribed by a veterinarian for the treatment or prevention of disease) (Scarlett 1994, Lund 2005,

Colliard 2008)

, feeding of treats (Russell 2000), feeding supplements (Robertson 1999), ad libitum feeding

(Russell 2000, Harper 2001)

. And for the environmental factors: owners over 40 years of age (Colliard

2008)

, underestimation of cat’s BCS by owners (Allan 2000, Colliard 2008), living indoors (Robertson 1999)

or in an apartment (Scarlett 1994), and only one or two cats living in the house (Robertson 1999). The

variety in study outcome can be dependent of differences in environment and the diet of cats

throughout the world. And every study has got his own design en methodologies, like the

routine of measurements, statistical analysis and the definition of obesity.

When risk factors for obesity can be identified, they can be used to prevent obesity and to

develop weight control programmes for cats to lower the risk for the clinical conditions.

There are no data that show that the prevalence of obesity in cats is truly increasing over a

long period where several generations can be compared. Donogue et al. (1998) showed that

there was no significant increase of obesity in the period from 1991 until 1996. And if the

prevalence is increasing, can this be contributed to a change in feeding characteristics like

feeding energy dense, highly digestible and palatable premium dry foods, or a feeding

regimen adapted to a working owner, or a change in environmental and management variables

over the last decennium, like the high incidence of neutering and decreased activity levels as

cats are increasingly confined indoors? (Russel 2000) In other words is there a change in risk

factors?

If the cause of increasing prevalence of obesity can be determined, weight control

programmes can be adapted accordingly and prevent or decrease the occurrence of obesity.

The first aim of this study is to identify the risk factors for obesity with the scope on feeding

characteristics. Second to evaluate if they changed during time and third to give an indication

if there has been a change in prevalence of obesity in the cat population in Palmerston North

since 1993.

5

“Prevalence of obesity and associated ‘Feeding Characteristics’

as risk factor for obesity in cats in Palmerston North”

2.

Materials and methods

Door-to-door interviews within the city limits of Palmerston North were conducted between

10 October 2007 and 14 December 2007. Palmerston North is located in the Manawatu region

on the southern half of the North Island of New Zealand. Palmerston North is a provincial city

with a population of 78.800 (Statistics New Zealand 2007) and about 24.600 households1.

2.1 Household and cat selection

An a priori decision was made to obtain information on 200 cats. A proportionally stratified,

random sampling approach was used to select the households and cats to be included in this

study. The households of Palmerston North were assigned to seven geo-demographic profile

groups, based on socioeconomic status (SES) and family orientation. Geo-demographic

profiles were determined using a clustering algorithm applied to the 2006 New Zealand

census data (Table 1). Note that profile group 2 (high SES – weak family) has been excluded

because households suitable to this particular profile did not exist in Palmerston North.

Family orientation is based on household composition, mortgaged home acquisition and

marital status. The Family Orientation score reflects family life cycle, which is a major

determinant of the types of goods and services required by households. Socioeconomic status

is a summary of educational, vocational and income measures and represent social resources.

The SES score represents social resources and hence the ability of households to purchase

goods & services of greater or lesser quality & expense1.

Profile Group

Households

(%)

High SES – Strong Family

5.5

Mid SES – Strong Family

32.0

Mid SES – Weak Family

18.9

Low SES – Strong Family

26.6

Low SES – Weak Family

4.7

Disadvantaged

12.3

Table 1. Proportion of households in Palmerston North within each geo-demographic profile

Addresses (street and number) in Palmerston North were randomly selected from the

Palmerston North phonebook. They were than sorted according to the different geodemographic profile groups, while remaining in order in which the addresses were drawn

from the phonebook. These addresses served as the starting addresses that would be used

during the study.

The number of cats sampled from each profile group was proportional to the number of

households within each profile group in Palmerston North. For example, profile group 1

(High SES – strong family) included 5,5 % of the households in Palmerston North,

subsequent from that, we required, 5,5 % of 200, 11 cats from addresses in profile group 1.

From the starting address every household in the street, got an information-flyer a couple of

days prior to the revisit of the street. The information flyer gave a short description what the

study was about and gave residents the opportunity to refuse participation or to make an

appointment.

1

Marketfind TM, Deltarg Distribution Systems Ltd, Auckland, New Zealand

6

‘Research project’ drs. C.A.M. Metekohy

Studentnr: 0248614

Subsequently door-to-door interviews were conducted from the starting address up the same

side of the street. The door-to-door visits in one street proceeded until data on 4 cats were

obtained. If the end of the street was reached before the required number of 4 cats, the

interviews were continued on the other side of the street. As soon as sufficient data were

obtained, the interviewers proceeded to the second starting address on the list and so forth,

until the required number of cats for the particular profile group was obtained.

A survey form was completed on every household that was visited and on every cat.

If there was no reply at any particular house, the interviewers revisited the address on two

further occasions on different days and at different times. If there was no reply after the third

visit no further attempts were made to contact the householders. The interviewers visited the

households between 09:00 hours and sundown (approximately 20:00 hours.), 7 days per

week.

Cats under one year of age were not included in the study. In multi-cat households only one

cat was included. The selection was based on the name closest to the beginning of the

alphabet, when all cats’ names in the household were listed in alphabetic order.

2.2 Questionnaire and body measurements

The potential for interviewer bias was limited by having a fixed questionnaire. And before the

start of the study the interviewers were trained in taking body measurements and assessing the

body condition scores (BCS) of cats. Chosen BCS by the interviewers were compared to each

other and observed, and if necessary corrected, by a an experienced supervisor during the

training.

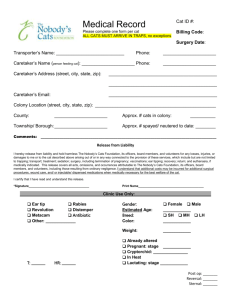

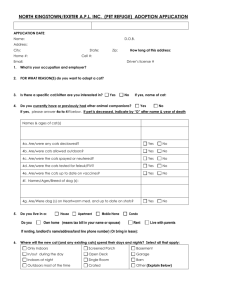

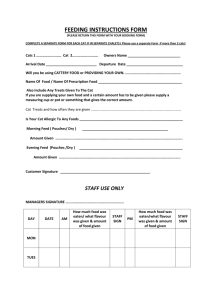

The questionnaire was divided into five sections, Signalment, Household variables, Cat

affinity variables, Cat feeding variables and Cat characteristics variables (Appendix I). Survey

questions were answered by simple responses (e.g. Yes, no, numbers) or with help of

showcards, to prevent confusion about answers at the data analysis.

Section Signalment obtained information about the cat’s age, sex and whether or not it had

been desexed. The section about Household variables sought information about the household

the cat lived in (number of people, age of the people, number of cats, and dog ownership).

Section Cat affinity contained one question that attempted to establish the relationship the

members of the household had with the cat (Appendix II, showcard one). Information on the

cat’s diet, like frequency of feeding and types of food fed was recorded in the Cat feeding

variables section. For answering these questions showcards two till four were used (Appendix

II). The section Cat characteristics included questions about the cat’s activity level, the

owner’s perception of the cat’s body condition and on the cat’s health, with showcard five and

six (Appendix II) for answering the questions.

After completing the questionnaire, the interviewers continued with the body measurements

of the cat. The cats were weighed on a set of portable scales (Ngata, model BW-2010; 20kg

max, 10g increments). The length of each cat was measured from the point where the spine

intersects with an imaginary transverse line through the cranial angle of both scapulae to the

angle created at the base of the tail when it is held erect. The forelimb was measured on the

palmar surface from the distal aspect of the digits (not including the claws) to the olecranon

with the limb and digits in full extension. Each measurement was performed at least twice to

ensure the results were repeatable.

The interviewers determined the BCS of each cat using a validated 9-point body condition

scoring system (Laflamme 1997). Both interviewers assessed each cat’s BCS independently

7

“Prevalence of obesity and associated ‘Feeding Characteristics’

as risk factor for obesity in cats in Palmerston North”

through inspection and palpation, and when the scores didn’t correspond, the interviewers

reached agreement through discussion. However disagreement only occurred with a small

number of cats during data collection, and the difference of assessed BCS between the

interviewers was never greater than one point in the scoringsystem.

The amount of diet intake by the cat, per day, was determined through owner’s estimation of

the amount of food the cat ate per day. This was then weighed on a kitchen scale (brand

unknown, 2kg max, 1g increments). After which the diet content, reported on the packinglabel, together with the Atwater coefficient were used to calculate the metabolizable energy.

2.3 Data Analysis

The obtained body condition scores were converted to a dichotomous variable, normal weight

or overweight, suitable for use as a dependent variable. Since the objective was to identify

risk factors associated with cat obesity, cats that were considered underweight (a BCS of 1,2

or 3) were not included in the analysis. Cats with a BCS of 4 or 5 were classified normal

weight and cats with a BCS of 6, 7, 8 or 9 were regarded as overweight. In this study no

distinction is made between overweight and obese cats.

Independent variables associated with multiple categories were re-categorised, where

possible, to avoid groups with very small numbers of observations. Re-categorisation was

performed in a way that ensured biologically meaningful conclusions could be made.

Continuous variables were grouped in categories based on quartiles to take in account for

non-linear effects.

For the purposes of this paper “premium” dry food included only highly digestible, high

calorie dry food, that is predominantly sold through veterinary clinics and Pet shops in New

Zealand. It excluded the high fibre, low calorie diets, defined by manufacturers as therapeutic

food for obesity, which are also supplied by manufacturers of ‘premium’ dry food.

A descriptive analysis was conducted, where the data distribution is characterized and

described and the findings are summarized, to obtain understanding of the data and the

population studied.

This was followed by a multivariable analysis of all the variables assessed in this study, to

identify the most important risk factor-variables and to investigate any confounding

interactions.

The variables were grouped in 4 risk factor groupings, based on biologically sensible

groupings of variables, namely cat characteristics, owner’s perception of their cat, household

characteristics and feeding variables (Appendix III, Table 4). The analysis was then

conducted in two phases, first stepwise logistic regression was run on the variables within the

four risk factor groupings to determine which variables were significant. This was done using

forward stepwise selection based on likelihood-ratio statistics with a p-value of < 0.05 for

entry. Subsequently the factors which had been statistically significant were combined and

analysed, using the same stepwise logistic regression.

Next the combined effect of the significant variables on the dependent variable were tested for

statistical significance, this is called a ‘interaction term’. With this calculation one can

determine how much variance is explained by the interaction of two or more variables.

The regression coefficients, which indicates the strength of the relationship between the

independent variable and obesity, were converted into odds ratios with 95% confidence limits.

Relevance of the models to the data was assessed using receiver operating characteristic

8

‘Research project’ drs. C.A.M. Metekohy

Studentnr: 0248614

(ROC) analysis. The area under the curve was estimated and its standard error was calculated

using the non-parametric distribution assumption.

Analyses were performed using the statistical software packages SPSS for Windows version

16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) and SAS for Windows version 9 (SAS Institute, Cary,

North Carolina, USA).

2.4 Ethics Approval

This study did not reach the threshold requiring approval by the Massey University Animal

Ethics Committee. This study was approved by the Massey University Human Ethics

Committee: Southern A (Application 07/55).

3.

Results

3.1 Descriptive Analysis

A total of 1045 households were visited and data on 215 cats were obtained. Of the remaining

830 households were 37 householders not at home after 3 visits, 87 householders refused or

were unable to participate, 459 households did not have a cat, 15 households had a cat less

than one year of age, 4 households had a cat and the owner was willing to participate but the

cat was absent on each of the three visits and for 228 households, the residents were not

contacted because the number of cats determined for that street had been reached prior to the

third visit (Table 2).

Households

Number

Participated

Not at home

Refused / unable to participate

No cat

< 1 year of age

Cat absent

Not contacted

215

37

87

459

15

4

228

Total visited

1045

Table 2. Visited Households

In total 15 cats were excluded from analysis. Nine cats were excluded because they had a

body condition score of 1, 2 or 3 and classified as thin. Five cats were excluded on medical

grounds. And one cat was excluded because it was to fractious to do the body measurements.

9

“Prevalence of obesity and associated ‘Feeding Characteristics’

as risk factor for obesity in cats in Palmerston North”

Reason exclusion

Thin

Medical Grounds

Number

9

Hyperthyroidism

Diabetes Mellitus

Treatment Fluoxetine

Treatment Clomipramine

Treatment Prednisone

1

1

1

1

1

1

15

Too fractious

Total

Table 3. Excluded cats

From the remaining data of 200 cats, 126 (63%) cats were classified as overweight and 74

(37%) as normal weight. The numbers of cats in each body condition score category is shown

in Figure 1.

80

70

Number of cats

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Body Condition Score

Figure 1. Distribution of BCS

Note that cats excluded on medical grounds are not shown

All the variables assessed as potential risk factors for obesity are shown in Table 4 (Appendix

III). Note that this part of the study is restricted to the feeding variables.

The data concerning the feeding variables show that 66% of the householders ensured that

food was always in their cat’s bowl. Half of the householders (56%) put food down for their

cat twice a day, 20% puts food down less frequently and 24% more frequently than two times

a day.

Dry food was most commonly fed; 87% of the respondents fed their cats dry food daily while

only 5% of the cats were fed dry food less frequently than once fortnightly or never.

10

‘Research project’ drs. C.A.M. Metekohy

Studentnr: 0248614

Of the householders that fed dry food to their cats, 72% indicated that the majority (> 95%) of

the dry food they gave to their cats was bought at the supermarket. Only 22% of the cats were

fed ‘premium’ dry foods the majority of the time.

Canned food was fed daily in over one-third (37%) of the households and less frequently than

once fortnightly or never in half of the households (49%).

Food in pouches was fed less frequently than once fortnightly or never to 66% of the 200 cats.

But if food in pouches was fed by respondents, it was usually daily (22%).

Note that the data of the energy intake have been excluded of this study, because we obtained a low

number of useful information about the dietary intake (see discussion).

3.2 multivariable analysis

The results of the stepwise multiple logistic regression of statistically significant variables are

shown in Table 5. The categories with an OR = 1 are set as reference. Regarding the feeding

variables model, this means that feeding ‘dry food less often than daily’ gives 0.3 ‘more’

change of developing obesity as feeding ‘dry food daily’. This indicates that feeding ‘dry food

less often than daily’ is protective to obesity compared to feeding ‘dry food daily’. In other

words, feeding dry food daily is a risk factor for obesity. The other feeding variables, not

shown in the table, were either not significant or explained by the influence of feeding dry

food in the model.

11

“Prevalence of obesity and associated ‘Feeding Characteristics’

as risk factor for obesity in cats in Palmerston North”

Model

Risk factor

Category

OR

95% CL

Cat characteristics

Neutered

No

0.12

0.01 – 1.05

Yes

1 (ref)

<=180

1 (ref)

181-186

2.98

1.25-7.12

187-197

2.85

1.18-6.88

>= 198

4.08

1.63-10.2

<=2

1 (ref)

3-7

1.84

0.73-4.65

8-12

4.53

1.7-12.01

>=13

8.69

2.02-36.41

Less often than daily

0.30

0.13-0.73

Daily

1 (ref)

Yes

0.56

No

1 (ref)

Overestimate

Not estimated

sample size too small

Correct

0.1

0.05-0.21

Underestimate

1 (ref)

<=180

2.39

0.88-6.45

181-186

2.98

1.08-8.17

187-197

4.42

1.55-12.4

>= 198

1 (ref)

<=2

2.30

0.78-6.79

3-7

5.45

1.67-17.87

8-12

13.80

2.73-59.7

>=13

1 (ref)

Overestimated

Not estimated

sample size too small

Correct

0.08

0.03-0.17

Underestimate

1 (ref)

Leg length (mm)

Age (years)

Feeding

How often dry food?

Environmental and cat

Less than 16 years old

management

children?

Owner perception

Overall model

BCS

Leg length (mm)

Age (years)

BCS

0.31-0.996

Table 5. Significant results of the stepwise multiple logistic regression

12

‘Research project’ drs. C.A.M. Metekohy

Studentnr: 0248614

The combined logistic-regression model, derived from the variables which had been

significant in the component models, yielded three remaining significant variables. These

included the cat’s leg length, its age and whether the owner underestimated the body

condition of the cat. The risk factor feeding dry food was explained by other factors in the

combined model.

Figure 2. ROC curves for the different models

Area Under the Curve

Asymptotic 95% Confidence

Interval

Test Result Variable(s)

Area

Std. Errora

Asymptotic Sig.b

Lower Bound

Upper Bound

Overall model

.847

.030

.000

.789

.906

Cat characteristics

.737

.037

.000

.664

.810

Owner perception

.758

.035

.000

.689

.828

Feeding

.560

.043

.160

.475

.645

.573

.042

.085

.490

.657

Environment and cat

management

a. Under the nonparametric assumption

b. Null hypothesis: true area = 0.5

Table 6. Predicted probabilities for all models

13

“Prevalence of obesity and associated ‘Feeding Characteristics’

as risk factor for obesity in cats in Palmerston North”

The suitability of the models to the data is expressed in de ROC curves presented in figure 2.

This is reflected in the area under the curve (Table 6), the greater the area under the curve, the

better is the degree of predictability of obesity by the model.

One can see that the area under the curve for the feeding model is 0.560 with a 95%

Confidence Interval from 0.475 till 0.645.

If the area under the curve is not significant different from 0.5, it means that from all the

animals predicted to be obese with this model, 50% is truly obese and 50% is actually not

obese. This indicates poor fit of the model. In contrary to the area under the curve for the

overall model of 0.847 (95% CI 0.789 – 0.906) which indicates a high degree of

predictability.

The significance of the models is also shown by the Sig value. A value smaller than 0.05 tells

us that the model is significant, the Sig value of the feeding variables model is 0.160 and not

significant and was removed from the overall model.

4.

Discussion

No claim can be made that the results of the studied population of cats can be simply

generalized to the whole New Zealand cat population. But the population in this study can be

considered as a healthy cat population and this study gives indications for risk factors which

could have their effect at other cat populations as well and from which measures can be taken.

Cats under one year of age were excluded from this study because obesity is unlikely to

develop in growing cats.

Cats were also excluded if they had a medical condition or if they were on any medication

which may have affected their body condition. We excluded 1 cat with Hyperthyroidism

because this induces increased metabolism, what can cause polyphagia and weight loss

(Galloway 1999)

which will affect the body condition of the cat. One cat was excluded based on the

veterinary diagnosis Diabetes Mellitus where a disturbed glucose metabolism (Hoenig 2007) can

affect the body condition score. 3 cats were excluded because they were treated with

Fluoxetine, Clomipramine or Prednisone. Fluoxetine (Prozac®, Reconcile®) is a human

antidepressant of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class, used in animals with

behavior problems. It changes the appetite, can cause vomiting and diarrhea in cats (Crowell-Davis

2005)

. Clomipramine (Clomicalm®) is also an antidepressant of the selective serotonin

reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class with the same side effects (Fidin repertorium 2009). Prednisone is a

corticosteroid and can cause polyphagia in cats.

In this study we found 63% of the cats overweight compared to 26% of the cats in 1993(Allan

2000)

, using the same population base. It is important to note that the studies used different

body condition scoring systems.

This study used Laflamme’s 9 point scale because it is globally accepted and validated. It has

been tested on it’s repeatability, reproducibility and predictability. Besides it is a cheap way

of assessing body composition and it’s easy to use (Laflamme 1997).

In 1993 they used a 5 point scale specifically designed for the paper. If we applied these

criteria to this study, by ‘binning’ the 9 point scale into the 5 point scale (BCS 1-2 = 1

(extremely thin); BCS 3-4 = 2 (thin); BCS 4-6 = 3 (normal weight); BCS 7-8 = 4

(overweight); BCS 9 = 5 (extremely overweight)), the prevalence of obesity would have been

27%, due to differences in categorisation of ‘overweight’ in between systems. We therefore

14

‘Research project’ drs. C.A.M. Metekohy

Studentnr: 0248614

indicate there is little evidence to support the hypothesis that the incidence of obesity in the

cat population of Palmerston North has increased over the period from 1993 to 2007. This is

contrary to the overall assumption that the prevalence of obesity in cats is increasing just like

it is in people in the western world.

To compare the data of this study and the data of 1993 effectively, and to conclude if there

has or hasn’t been any change in prevalence and riskfactors, statistic analysis of the data and

the BCS distribution of this study adjusted to the 5 point scale has to be done.

Besides the weight-distributions of the cats can also be used to make a comparison between

this study and the one in 1993, this way the use of two different scoring systems, and the

trouble to compare them can be avoided. If there is an increased number of heavy cats

compared to the study in 1993, it is likely that the prevalence of obesity increased in time.

We see great differences in the prevalence in between our study and several studies conducted

in other countries. This can be due to variations in management practices, like the diets on the

market and the way of housing. But they can also be explained by different methods of

assessment of body condition or by real differences in the prevalence of obesity in time.

With respect to the other objective of this study, that the high incidence of obesity is

associated with feeding characteristics, we have shown that feeding of dry food on a daily

basis (both ‘premium’ and ‘non premium’) was a risk factor in the feeding variables model.

One suggested explanation of feeding dry food as a risk factor is based on the fact that a lot of

dry food contains a high percentage of carbohydrates. Cats have, due to it’s metabolic

adaptations as a strict carnivore (MacDonald 1984), no dietary requirements for carbohydrates. This

has led to speculations that conventional dry cat foods may predispose to weight gain and that

a low carbohydrate diet might facilitate weight loss. But this is invalidated by the study of

Backus et al. (2007), that showed that high dietary carbohydrate did not induce weight gain in

domestic cats.

The study of 1993 didn’t show feeding dry food as a risk factor. Back then fewer people in

the study fed dry food daily, 100 out of 182, to 176 out of 200 people in this study. If dry food

is fed more often, it may have a greater influence on the body condition of the cat. More dry

food consumption can also be concluded from cat food sales figures2. It seems there is a

continuing slow trend towards dry foods over the years and there has been a slow shift within

the dry foods market towards more energy dense (and higher priced) products. Unfortunately

the exact sales data are not available, so it’s not possible to quantify this.

Second it is suggested that dry food, especially the premium ones, is more palatable

nowadays. A study of Houpt and Smith (1981) has shown that cats have taste preferences and

subsequently this can influence the amount of diet intake of a very palatable food and

increases the risk of obesity.

However, the risk factor ‘feeding dry food’ was explained by other factors in the combined

model.

‘Premium’ energy dense dry cat food-brands are increasingly more available and

recommended by veterinary clinics, so another aim of this study was to determine if feeding

‘premium’ dry food was a risk factor for obesity. This was not the case in this study,

in contrary to the studies conducted in the United States (Scarlett 1994, Lund et al. 2005) which showed

that obese cats were more likely to be fed a premium or therapeutic food. A reason for this

remarkable difference could be that this study excluded the therapeutic (diets prescribed for

specific medical problems, including obesity) foods from our study to prevent confounding,

because it’s difficult to determine whether obesity was caused by the diet or the diet was

From: ‘Catfood Market’ in the Newsletter of The New Zealand Petfood Manufacturers Association Inc.

Devonport, Auckland

2

15

“Prevalence of obesity and associated ‘Feeding Characteristics’

as risk factor for obesity in cats in Palmerston North”

‘prescribed’ for obesity. Foods bought at a veterinary clinic or a pet store are more likely to be

accompanied with a clear advise about the amount of food a cat is allowed to get per day.

This could suggest that there is a decreased risk of overfeeding, if cat owners are guided by a

veterinarian or other expert.

In this study we tried to split the influence of ‘ad libitum’ feeding and the frequency that food

is offered by the owner as risk factors of obesity in cats. The definition of ad libitum feeding

in this study was, ‘the owner puts food down once a day and ensures the bowl is never empty.

This study didn’t show ‘ad libitum’ feeding to be a risk factor for obesity, in accordance to the

study in 1993 (Allan 2000) and others (Scarlett 1994, Colliard 2008) . It is believed that cats are able to

regulate their dietary intake to maintain adequate macronutrient and energy intake. Small

scale studies showed that cats can regulate their dietary intake over a long time and reach

eventually a stable energy intake (Goggin 1993) and cats will eat frequent small meals when they

are freed of the usual constraints over access to food (Mugford and Thorne 1978). Although some

researchers have shown ad libitum feeding to be a risk factor (Russell 2000, Harper 2001) for obesity.

With ad libitum feeding, the food in de bowl may be stale and unpalatable by the end of the

day. We therefore hypothesised that the frequency owners put food down for their cats could

influence their appetite, irrespective of whether access of food was ad libitum.

The owner who ensures the food bowl is always full by providing often small amounts of

food may encourage their cat to eat more by drawing the cat’s attention to the food bowl and

by ensuring the food is always fresh and palatable.

However, the frequency that food was offered was not identified as a risk factor in this study.

Just like it was shown in de studies of Donogue et al. (1998), Russel et al. (2000), and Michel

et al. (2005).

A limitation of this study is that the actual amount of food- and energy intake by cats is not

calculated, while both quantity and quality must be considered when evaluating the effect of a

diet on bodyweight and body condition.

The data resulting from the diet measurements, done by the interviewers were not useful for

calculating the actual amount of energy intake because several people in 1 household were

feeding the cat, and most of them didn’t give the same amount of food every day. At other

households there was living more than one cat, making it difficult to measure the energy

intake of just one cat. The use of ‘continuous feeders’ or giving more than one brand of food

makes calculation of the exact energy intake not possible.

These problems can be overcome by not depending on the estimation of the amount of food

given to the cat by the owners, but measuring the amount given to a cat in a week by the

interviewers, through visiting the addresses twice and weigh the cat food package on both

occasions. The difference between the weights is the amount of food the cat ingested.

In the period of time this study was conducted, there wasn’t enough time to visit the

households twice.

Using the diet content, reported on the packing-label, makes the calculation of dietary intake

unreliable because some manufacturers report only the average analysis and metabolizable

energy (ME) of their foods, and others report only guaranteed analysis. The ash content is

often not included in the latter and must be guessed before the carbohydrate content of the

diet can be calculated (Hill 2006). At last there are limited data on the digestibility of dietary fibre

in cats, but it still represents a source of energy for the cat and therefore diets with low or high

fibre content influence the metabolizable energy. More research is needed to correct for the

differences in digestibility and thus energy intake and prevent under- respectively

overestimation of the ME (Butterwick 1998). Besides commercial databases of ME density of

petfoods are not available (Hill 2006).

16

‘Research project’ drs. C.A.M. Metekohy

Studentnr: 0248614

One have to evaluate if measuring diet and energy intake of a cat gives enough information

about exceeding the energy expenditure of that cat. Recommendations as how much food or

calorie intake cats require, are based on the average requirements of healthy laboratory cats,

without stress and with a normal body condition, undertaking modest amounts of exercise in a

thermo neutral environment. But most cats do not conform these norms, and one has to adjust

these recommendations for individual physiological differences based on age, breed, etc.,

maintaining body temperature in cold and warm ambient temperatures and changes in energy

requirements with disease or stress. Further adjustments have to be taken for the activity level

and changes of energy requirements for grow, lactation and gestation (Hill 2006).

The other feeding variables didn’t turn out be significant in this study. This could be due to

the relative small numbers of owners giving other foods to cats or the low frequency of

presenting these foods to cats, comparing to dry food.

Nevertheless they have to be considered when evaluating the effect of diet on body weight

and condition, because they still contribute to the calorie intake and have been shown to be

risk factors by some authors. Russell (2000) showed treat feeding had influence on

developing obesity. Supplements were also associated with heavier cats (Robertson 1999) but one

has to evaluate what the supplements are for, because some can be prescribed for the

management of overweight cats (Roudebush 2008) and would be a confounder in the evaluation of

risk factors for obesity.

This study has failed to show any feeding variable as independent risk factor, just like the

study conducted in 1993 (Allan 2000) and Colliard (2008).

17

“Prevalence of obesity and associated ‘Feeding Characteristics’

as risk factor for obesity in cats in Palmerston North”

5.

Conclusion

Our data didn’t show the expected increase in the incidence of obesity in the studied cat

population of Palmerston North. Although this is difficult to conclude because different

scoring systems are used in both studies. Feeding dry foods (both ‘premium’ and ‘non

premium’) was associated with a increased risk of obesity in the feeding variables model,

however this was explained by other factors in the combined model. The increasingly

popularity of ‘premium’ dry foods didn’t seem to contribute to the development of obesity.

The influence of the frequency of feeding, giving other foods than dry food and supplements

to cats didn’t turn out to be a significant risk for obesity. In conclusion this study has failed to

show any feeding variable as independent risk factor.

Apparently obesity is not caused by feeding variables and it would be likely that other factors

override the cat’s ability to regulate energy intake and might be associated with overingestion, if there is abundant food available.

It’s important to acknowledge that prevention of obesity is the best intervention, because

managing obesity is relatively difficult in practice, due to the numerous variables which can

influence the development of the disease. Some of these variables can be difficult to adjust,

like age, gender, neuter status. Therefore and because dietary management is one of the

easiest and the most practical method to attack over ingestion in cats, this is the primary

method to prevent and ‘treat’ obesity.

To prevent obesity, veterinarians have to advise clients regarding appropriate feeding

management of new kittens or cats in a household (Burkholder 1998). At any time during the

animal’s life where a change in circumstances may result in a greater risk of developing

obesity (if any risk factor is present), the owner should be advised accordingly (Sloth 1992). It’s

important to adjust energy intake, to the change in energy expenditure in individual animals,

to prevent weight gain at those critical times (Harper 2001).

To treat obesity through dietary management, energy intake has to be reduced to achieve

weight loss (Butterwick 1994). It’s therefore important to determine the amount of weight loss and

the energy expenditure of a individual animal to set a limit for daily caloric intake (Burkholder

1998)

. A complete and balanced diet has to be chosen. A lot of research is done to figure out

which diet will safely contribute to weight loss. Traditional methods used low fat, high fibre

diets to reduce caloric intake and bodyweight, while maintaining satiety. Newer concepts

include altering an animals’ metabolism by use of low carbohydrate, high protein foods

(Roudebush 2008)

. Another ‘treatment’ of obesity is the supplementation of dietary L-carnitine to

foods designed for weight management. Carnitine plays a central role in many cellular

processes, most of which are related to fat metabolism and energy production and can provide

beneficial effects in obese cats (Roudebush 2008), but more research is required to proof it’s

contribution to weight loss.

Finally it is important to maintain the desirable weight. This can be accomplished if dietary

habits are continued after successful weight loss. One has to proceed with portion controlled

feeding and monitoring of the cat by owner and veterinarian to maintain the ideal weight

(Burkholder 1998)

.

18

‘Research project’ drs. C.A.M. Metekohy

Studentnr: 0248614

Acknowledgements

I like to acknowledge Nick Cave and Frazer Allan, our supervisors in New Zealand, for the

opportunity to do research at Massey University, for all the preparation work prior to our

arrival, the help during data collection, answering all our questions, warranting our safety

during interview-hours and making our stay in New Zealand even more pleasant.

I also like to acknowledge Henk Everts for his help with completing the research proposal and

this article, his constructive comments and for his patience while waiting for any result.

I like to acknowledge the support of Nestle Purina, Massey University and the Royal

Veterinary College (London) for funding the study in time and kind.

Besides I want to thank Dirk Pfeiffer for his contribution to the statistic analysis.

Of course I want to thank Sanne Lien Schokkenbroek, with whom I conducted this study, for

her support, her translations during interviews and the good time we had in New Zealand.

19

“Prevalence of obesity and associated ‘Feeding Characteristics’

as risk factor for obesity in cats in Palmerston North”

References

Allan, F.J., Pfeiffer, D.U., Jones, B.R., Esslemont, D.H.B., Wiseman, M.S. A cross-sectional

study of risk factors for obesity in cats in New Zealand. Preventive Veterinary Medicine

(2000) 46, 183-96

Backus, R.C., Cave, N.J., Keisler, D.H. Gonadectomy and high dietary fat but not high

dietary carbohydrate induce gains in body weight and fat of domestic cats. British Journal of

Nutrition (2007) 98, 641-50

Burkholder, W.J., Bauer, J.E., Foods and Techniques for managing obesity in companion

animals. Journal of American Veterinary Medical Association (1998) 212, 658-2

Burkholder, W.J., Toll, P.W. Obesity. In: Hand, M.S., Thatcher, C.D., Reimillard, R.L.,

Roudebush, P., Morris, M.L., Novotny, B.J., editors. Small animal clinical nutrition, 4th

edition. Topeka, KS: Mark Morris Institute. 2000 p. 401-30

Butterwick, R.F., Wills, J.M., Sloth, C., Markwell, P.J. A study of obese cats on a caloricontrolled weight reduction programme. Veterinary Record (1994) 134, 372-7

Butterwick, R.F., Hawthorne A.J., Advances in Dietary Management of Obesity in Dogs and

Cats. Journal of Nutrition (1998) 128, 2771S-2775S

Butterwick, R.F., How fat is that cat? Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery (2000) 2, 9194

Chiaramonte D., Greco D. S., Feline Adrenal Disorders. Clinical Techniques in Small Animal

Practice (2007) 22, 26-31

Colliard, L., Paragon, B.M., Lemuet, B., Benet, J.J., Blanchard, G. Prevalence and risk

factors of obesity in an urban population of healthy cats. Journal of Feline Medicine and

Surgery (2008), doi:10.1016/j.jfms.2008.07.002

Coppack, S.W., Proinflammatory cytokines and adipose tissue. Proceedings of the Nutrition

Society (2001) 60, 349-56

Crowell-Davis, S.L., Murray, T., Veterinary psychopharmacology. Wiley-Blackwell (2006)

p.86 - 93

Fidin Repertorium (2009) http://repertorium.fidin.nl/

Galloway P., Feline Hyperthyroidism. Proc of the Companion Animal society of the NZVA.

FCE Pub (1999) 191, 43-50

German A.J. The Growing Problem of Obesity in Dogs and Cats. The Journal of Nutrition

(2006) 136, 1940S-1946S

German, A.J., Holden, S.L., Moxham, G., Hackett, R., Rawlings, J., A simple, reliable tool for

owners to assess the body condition of their dog or cat. Journal of Nutrition (2006) 136,

2013S-3S

20

‘Research project’ drs. C.A.M. Metekohy

Studentnr: 0248614

Goggin, J.M., Schryver, H.F., Hintz, H.F. The effect of ad libitum feeding and caloric dilution

on the domestic cat’s ability to maintain energy balance. Feline Practice (1993) 21, 7-11

Harper, E.J., Stack, D.M., Watson T.D.G., Moxham, G., Effect of feeding regimens on body

weight, composition and condition score in cats following ovariohysterectomie. Journal of

Small Animal Practice (2001) 42, 433-8

Hill, R.C., Challenges in Measuring Energy Expenditure in Companion Animals: A

Clinician’s Perspective. Journal of Nutrition (2006) 136, 1967S-1972S

Hoenig, M., Thomaseth, K., Waldron, M., Ferguson, D.C., Insulin sensitivity, fat distribution,

and adipocytokine response to different diets in lean and obese cats before and after weight

loss. The Amreican Journal of Physiology (2007) 292, 227-234

Houpt, K.A., Smith, S.L. Taste preferences and their relation to Obesity in Dogs and Cats.

The Canadian Veterinary Journal (1981) 22, 77-81

Jaso-Friedmann, L., Leary, J.H., Praveen, K., Waldron, M., Hoenig, M. The effects of obesity

and fatty acids on the feline immune system. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology

(2008) 122, 146-152

Laflamme, D.P., Development and validation of a body condition score system for cats: a

clinical tool. Feline Practice (1997) 25, 13-8

Laflamme, D.P., Understanding an Managing Obesity in Dogs and Cats. Veterinary Clinics

Small Animal Practice (2006) 36, 1283-1295

Lund, E.M., Armstrong, P.J., Kirk, C.A., Klausner, J.S. Prevalence and Risk Factors for

Obesity in Adult Cats from Private US Veterinary Practices. International Journal of Applied

Research in Veterinary Medicine (2005) 3, 88-96

McDonald, M.L., Rogers, Q.R., Morris, J.G. Nutrition of the domestic cat, a mammalian

carnivore. Annual Review of Nutrition (1984) 4, 521-62

Miller, D., Bartges, J., Cornelius, L., et al. Tumor necrosis factor a levels in adipose tissue of

lean and obese cats. Journal of Nutrition (1998) 128, 2751S-2S

Michel, K.E., Bader, A., Schofer, F.S., Barbera, C., Oakley, D.A., Giger U. Impact of timelimited feeding and dietary carbohydrate content on weight loss in group-housed cats. Journal

of Feline Medicine and Surgery (2005) 7, 349-355

Munday, H.S., Booles, D., Anderson, P., et al. The repeatability of body condition

measurements in dogs and cats using dual energy X-ray Absorptiometry. Journal of Nutrition

(1994) 124, 2619S-2621S

Mugford, R.A., Thorne, C. Comparative studies of meal patterns in pet and laboratory

housed dogs and cats. In: Anderson, R.S (ed), Nutrition of the Dog and Cat. Oxford, UK:

Pergamon Press, (1978) p. 3-14

21

“Prevalence of obesity and associated ‘Feeding Characteristics’

as risk factor for obesity in cats in Palmerston North”

Robertson, I.D., The influence of diet and other factors on owner-perceived obesity in

privately owned cats from metropolitan Perth, western Australia. Preventive Veterinary

Medicine (1999) 40, 75-85

Roudebush, P., Schoenherr, .D., Delaney, S.J. An evidence-based review of the use of

nutraceuticals and dietary supplementation for the management of obese and overweight pets.

Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association (2008) 232, 1646-55

Roudebush, P., Schoenherr, .D., Delaney, S.J. An evidence-based review of the use of

therapeutic foods, owner education, exercise, and drugs for the management of obese and

overweight pets. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association (2008) 233, 717-25

Russell, K., Sabin, R., Holt, S., Bradley, R., Harper, E.J., Influence of feeding regimen on

body condition in the cat. Journal of Small Animal Practice (2000) 41, 12-7

Scarlett, J.M., Donoghue, S., Saidia, J., Wils, J. Overweight cats: prevalence and risk factors.

International Journal of Obesity Related Metabolic Disorders. (1994) 18, S22-8

Scarlett, J.M., Donoghue, S. Associations between body condition and disease in cats. Journal

of the American Veterinary Medical Association (1998) 212, 1725-31

Scott-Moncrieff, J.C. Clinical Signs and Concurrent Diseases of Hypothyroidism in Dogs and

Cats. Veterinary Clinics Small Animal Practice (2007) 37, 799-22

Sloth, C. Practical management of obesity in dogs and cats. Journal of Small Animal Practice

(1992) 33, 178-182

Statistics New Zealand 2007 http://www.stats.govt.nz/NR/rdonlyres/4977BFC8-5752-461B-85AF92C93B18AB4E/0/Dec07_PalmerstonNorthCity.pdf

22

‘Research project’ drs. C.A.M. Metekohy

Studentnr: 0248614

Appendix I

Cat Obesity Study

CAT DATA SHEET

Houshehold Identifier Code ...........................................................................................

How many cats live in the household? ..........................................................................

Cat Number ...................................................................................................................

5

SIGNALMENT

What is the name of your cat? .......................................................................................

How old is your cat? ......................................................................................................

What sex is your cat?

M (1)

F (2)

Has your cat been spayed or castrated?

Yes (1)

No (2)

10

HOUSEHOLD VARIABLES

How many people usually live in the household? ..........................................................

And how many of those people in the household are:

over 60 years of age? .........................................................................................

less than 16 years of age? ..................................................................................

How many dogs live in the household? .........................................................................

15

CAT AFFINITY VARIABLE

[Showcard 1] Which of these statements best describes the relationship of your cat to the

members of the household? ...........................................................................................

CAT FEEDING VARIABLES

Do you usually ensure that your cat’s food bowl always contains food?

Yes (1)

No (2)

[Showcard 2]

How often do you put food down for your cat? ..................................

[Showcard 3]

How often do you feed your cat:

Dry cat food? .............................................................................

Canned cat food? ......................................................................

20

Cat food in pouches? .................................................................

Rolls or chubs? ..........................................................................

Milk? ............................................................................................

Table scraps? ............................................................................

Fresh meat or fish? ....................................................................

25

23

“Prevalence of obesity and associated ‘Feeding Characteristics’

as risk factor for obesity in cats in Palmerston North”

Vitamins and supplements? .......................................................

[Showcard 4]

Of the dry food that is fed, how much of it is:

Iams brand? ...............................................................................

Hills brand? ................................................................................

Purina brand? ............................................................................

Royal Canin brand? ...................................................................

30

Proplan brand? ..........................................................................

Other brands? ............................................................................

Of the dry food that is fed, how much of it is ‘lite’ or low-calorie?........

............................................................................................................

Have you fed your cat a diet prescribed by your veterinarian in the last 6 months?

Yes (1)

No (2)

If yes, probe: ..................................................................................................................

........................................................................................................................................

........................................................................................................................................

What was the diet called? ..............................................................................................

For what condition was the diet prescribed? .................................................................

........................................................................................................................................

CAT CHARACTERISTIC VARIABLES

[Showcard 5] How active do you consider your cat to be? ..........................................

35

[Showcard 6] Which description best describes your cat? ...........................................

Has your cat been on medication prescribed by your veterinarian in the last 6 months?

Yes (1)

No (2)

If yes, probe: ..................................................................................................................

........................................................................................................................................

........................................................................................................................................

What was the drug(s) called? ........................................................................................

For what condition was the drug prescribed? ................................................................

........................................................................................................................................

........................................................................................................................................

Weight ...........................................................................................................................

BCS ...............................................................................................................................

42

Leg Length ....................................................................................................................

Body Length ..................................................................................................................

24

‘Research project’ drs. C.A.M. Metekohy

Studentnr: 0248614

Appendix II

Showcard One

1.

We dislike our cat and would rather not have it around.

2.

Our cat is not important to us. We don’t give it a lot of attention.

3.

Our cat is of some importance to us. We like having it around.

4.

Our cat is important to us. It is a part of our family.

5.

Our cat is very important to us. We treat it like our child.

Showcard Two

1.

More than three times per day

2.

Three times per day

3.

Twice per day

4.

Once daily

5.

Every second day

6.

Less frequently than every second day

Showcard Three

1.

Daily

2.

Every second or third day

3.

Once weekly

4.

Once fortnightly

5.

Less often than once a fortnight

6.

Never

25

“Prevalence of obesity and associated ‘Feeding Characteristics’

as risk factor for obesity in cats in Palmerston North”

Showcard Four

1.

Greater than 95% of it.

2.

Around three-quarters of it.

3.

Around half of it.

4.

Around one-quarter of it.

5.

Less than 5% of it.

6.

None of it.

Showcard Five

1.

Extremely overactive

2.

Overactive

3.

Normally active

4.

Inactive

5.

Extremely inactive

Showcard Six

1.

Extremely thin

2.

Thin

3.

Normal weight

4.

Overweight

5.

Extremely overweight

26

‘Research project’ drs. C.A.M. Metekohy

Studentnr: 0248614

Appendix III

Table 4 Variables assessed as potential risk factors for obesity

Model

Cat characteristics

Owner’s perception

Environmental and

cat management

variables

Feeding variables

Variable

Category levels

59

40

31

13

O’weight

(%)

41

60

69

88

9

190

89

35

11

65

Male

Female

108

92

34

40

66

60

Level of activitya

Inactive

Normal

Overactive

26

152

22

19

38

55

81

63

46

Leg length (mm)a

≤ 180

181 – 186

187 – 197

≥ 198

55

50

49

46

55

30

35

26

46

70

66

74

Body length (mm)

≤ 341

342 – 362

363 – 381

≥ 382

50

53

52

45

48

42

33

24

52

59

67

76

Affinity to cat

Not important or some importance

Important or “like our child”

21

179

48

36

52

64

Owner’s estimate of BCSa

Underestimated

Correctly estimated

Overestimated

96

102

2

13

59

100

88

41

0

14

55

38

51

11

31

36

27

45

43

18

42

64

73

55

57

82

58

Age (years)a

≤2

3–7

8 – 12

≥ 13

Desexed?a

Entire

Desexed

Gender

Geo-demographic profile

High SES – Strong Family

Mid SES – Strong Family

Mid SES – Weak Family

Low SES – Strong Family

Low SES – Weak Family

Disadvantaged

Cats

(n)

29

87

58

24

Normal

(%)

Number of people in

household?

1

2

≥3

32

67

101

25

33

44

75

67

56

Number of people over 60

years of age?

0

1

2

155

26

19

41

27

21

59

73

79

Have children less than 16

years of age?a

No

Yes

118

82

31

45

69

55

Number of cats?

Single

Multiple

138

62

35

42

65

58

Have dogs?

No

Yes

156

44

35

46

65

55

Food bowl always full?

Yes

No

112

88

39

34

61

66

How often do you put food

down?a

>3 times per day

3 times per day

14

31

14

39

86

61

27

“Prevalence of obesity and associated ‘Feeding Characteristics’

as risk factor for obesity in cats in Palmerston North”

a

twice per day

once daily or less often

113

42

35

50

66

50

How often do you feed dry

food?a

Daily

Less often than daily

176

24

34

63

67

38

How much premium dry food

do you feed?

>50%

5-50%

None

32

17

151

28

24

40

72

77

60

How often do you feed

canned food?

Daily

Every 2-3 days

Once weekly or less often

72

21

107

38

48

35

63

52

65

How often do you feed food

in pouches?

Daily

Every 2-3 days

Once weekly or less often

44

15

141

36

33

38

64

67

62

Do you feed rolls or chubs?

Fed

Not fed

9

191

33

37

67

63

How often do you feed milk?

Daily

Every 2-3 days

Once weekly

Once fortnightly

Less often than once a fortnight

Never

18

11

14

7

18

132

39

27

43

71

44

34

61

73

57

29

56

66

How often do you feed table

scraps?

Daily

Every 2-3 days

Once weekly

Once fortnightly

Less often than once a fortnight

Never

13

22

14

13

20

118

46

55

36

46

45

31

54

46

64

54

55

70

How often do you feed fresh

meat or fish?

Daily

Every 2-3 days

Once weekly

Once fortnightly

Less often than once a fortnight

Never

21

17

31

27

41

63

19

53

39

52

32

35

81

47

61

48

68

65

Do you give supplements?

Yes

No

27

173

37

37

63

63

Indicates p < 0.1 for each variable

28