Listening Skills

advertisement

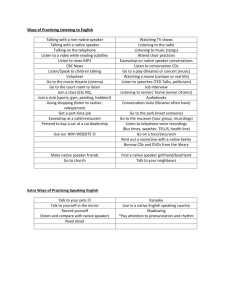

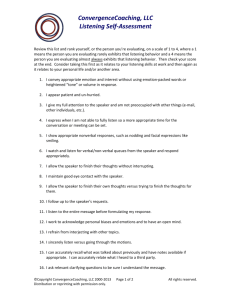

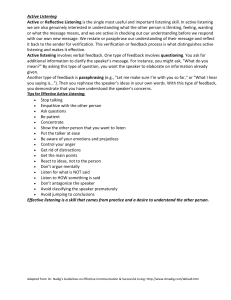

Listening Skills General Information Context: The most difficult leap in negotiations (or in most discussions, for that matter), is to get past positions (what someone is saying) to understanding their interests (why they are saying it). Yet understanding interests is critical to effective dialogue. The single most effective way to accomplish this leap is to listen – truly listen – to the speaker. Listening at depth is not an easy skill, especially in many western cultures where power seems to be associated with how much is said (and sometimes with how loudly). Objective: To offer two skill-sets for listening: active listening, which is a set of ground rules for polite, constructive discourse; and transformative listening, which allows for deeper work, useful especially when powerful emotion is present. Part 1: Active Listening Context: In advance of any formal or informal negotiations, it is worth talking in a group about ground rules. These should be suggested by the participants (although an instructor/facilitator can help with suggestions), adopted by consensus, and posted in a visible place as a “touch-stone” document. Example: 1) When a group convenes, ask them for help in crafting a list of ground rules for the negotiations. If typical, the group will come up with a set similar to: One speaker at a time, signaled by, e.g. upturned nameplates, a speakers list, etc.; Every speaker gets to finish uninterrupted; No direct accusations; “generic” examples can be used instead; All should try to participate fully; Others? 2) The next step is to focus on active listening skills, including (more skills are listed in Table 1): Repeat main points. Repeat the main points of the speaker (this lets the speaker know that they have really been heard, a powerful psychological message, as well as helping to focus the dialogue); Ask. Ask (non-threatening) questions. Useful both to better understand the speaker, and also to reassure them that you are really listening; "I" not "you" statements. When speaking, speak in the first person – "I" not "you" – setting a tone which is more reflective and less confrontational; Future, not history. Speak in the future or present tense, not the past. This further reduces the possibility of accusations, and allows for greater cooperation to build for a common future. [In many settings, a period of venting of past grievances does need to be set aside – that, after all is a main reason why some negotiators initially participate. It should be done in as productive a way as possible, and then put aside for the duration.] Paying Attention - Face the person who is talking. - Notice the speaker’s body language; does it match what he/she is saying? - Listen in a place that is free of distractions, so that you can give undivided attention. - Don’t do anything else while you are listening. Eliciting - Make use of “encourages” such as “Can you say more about that?” or “Really?” Use a tone of voice that conveys interest. Ask open questions to elicit more information. Avoid overwhelming the speaker with too many questions. Give the speaker a chance to say what needs to be said. Avoid giving advice, or describing when something similar happened to you. Reflecting - Occasionally paraphrase the speaker’s main ideas, if appropriate. Occasionally reflect the speaker’s feelings, if appropriate. Check to make sure your understanding is accurate by saying “It sounds like what you mean is...Is that so?” or “Are you saying that you’re feeling...” Source: Kaufman (2002), p. 220 Figure 1: Techniques of Active Listening Part 2: Transformative Listening Context: When real emotion is present, classic problem-solving approaches to dialogue are generally not practical. Water, as we have seen, can be tied in to all levels of existence, from basic survival to spiritual transformation. Often, water negotiations are tied inextricably to regional conflicts, including in some of the most contentious regions in the world, and negotiators carry the weight of those disputes with them into the dialogue setting. When a participant is clearly distraught, and “objective” problemsolving seems not to be viable, it may be worth stepping back for a few moments, giving the participant the space and time to work through their issue. In such a setting, a listener should take over (often the mediator or facilitator), in a process of “transformative listening”. Here, in contrast to “active listening”, the listener is not trying to facilitate a healthy dialogue, but rather making him- or herself absolutely present for the speaker to get deeply into their issues. When real energy is present, it is NOT helpful to offer: advice reassurance opinion curiosity presence Instead, be present entirely for the speaker, knowing that resolution comes from within. Listen with an open heart; Pause – the gift of silence; Track or reflect (statements or open-ended clauses) Only when speaker’s energy allows (stop if grief or mourning; just be present)... Ask permission Offer without insistence Check for completeness Listening Good listening is more difficult than we think. Listening seems to be a very easy thing to do. In reality we think we listen, but we actually hear only what we want to hear! This is not a deliberate process, it is almost natural. Listening carefully and creatively (picking out positive aspects, problems, difficulties and tensions) is the most fundamental skill for facilitation. Therefore, we should try to understand what can hinder it, in order to improve our skills. Listed below are so-called barriers to listening that may prevent effective and supportive listening. Being aware of them will make it easier to overcome them. Listening barriers On-off listening This unfortunate listening habit comes from the fact that most people think about four times faster than the average person can speak. Thus the listener has about three to four minutes of ‘spare thinking time’ for each minute of listening. Sometimes the listener may use this extra time to think about her or his own personal affairs and troubles instead of listening, relating and summarizing what the speaker has to say. This can be overcome by paying attention to more than just the speech, but also watching body language like gestures, hesitation etc. Red-flag listening To some people, certain words are like a red flag to a bull. When they hear them, they get upset and stop listening. These terms may vary for every group of participants, but some are more universal such as “tribal”, “black”, “capitalist”, and “communist” etc. Some words are so ‘loaded’ that the listener tunes out immediately. The speaker loses contact with her or him and both fail to develop an understanding of the other. Open ears – closed mind listening Sometimes ‘listeners’ decide quite quickly that either the subject or the speaker is boring, and what is being said makes no sense. Often they jump to the conclusion that they can predict what the speaker will say and then conclude that there is no reason to listen because they will hear nothing new if they do. Glassy-eyed listening Sometimes ‘listeners’ look at people intently, and seem to be listening, although their minds may be on other things. They drop back into the comfort of their own thoughts. They get glassy-eyed, and often a dreamy or absent-minded expression appears on their faces. If we notice many participants looking glassy-eyed in sessions, we have to find an appropriate moment to suggest a break or change in pace. Too-deep-for-me listening When listening to ideas that are too complex and complicated, we often need to force ourselves to and to understand it. Listening and understanding what the person is saying might result in us finding the subject and the speaker quite interesting. Often if one person does not understand, others do not either, and it can help the group to ask for clarification or an example if possible. Don’t-rock-the-boat listening People do not like to have their favorite ideas, prejudices and points of view overturned and many do not like to have their opinions challenged. So, when a speaker says something that clashes either with what the listener thinks or believes in, then s/he may unconsciously stop listening or even become defensive. Even if this is done consciously, it is better to listen and find out what the speaker thinks first, in order to understand his or her position fully. Responding constructively can be done later. Do’s and don’ts of listening When listening we should try to do the following: show interest be patient be understanding be objective express empathy search actively for meaning help the speaker develop competence and motivation in formulating thoughts, ideas and opinions cultivate the ability to be silent when silence is necessary When listening we should avoid doing the following: pushing the speaker arguing interrupting passing judgment too quickly in advance giving advice unless it is requested by the other person jumping to conclusions letting the speaker’s emotions affect own too directly