Mother Culture, or Only a Sister

advertisement

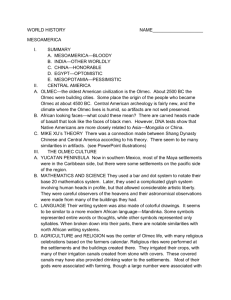

Mother Culture, or Only a Sister? By John Noble Wilford On a coastal flood plain etched by rivers flowing through swamps and alongside fields of maize and beans, the people archaeologists call the Olmecs lived in a society of emergent complexity. It was more than 3,000 years ago along the Gulf of Mexico around Veracruz. The Olmecs, mobilized by ambitious rulers and fortified by a pantheon of gods, moved a veritable mountain of earth to create a plateau above the plain, and there planted a city, the ruins of which are known today as San Lorenzo. They left behind palace remnants, distinctive pottery and art with anthropomorphic jaguar motifs. Most impressive were Olmec sculptures: colossal stone heads with thick lips and staring eyes that are assumed to be monuments to revered rulers. The Olmecs are widely regarded as creators of the first civilization in Mesoamerica, the area encompassing much of Mexico and Central America, and a cultural wellspring of later societies, notably the Maya. Some scholars think the Olmec civilization was the first anywhere in America, though doubt has been cast by recent discoveries in Peru. Archaeologists have split sharply over how much influence the Olmecs had on contemporary and subsequent Mesoamerican cultures. Were Olmecs the "mother" culture? Or were they one among "sister" cultures whose interactions through the region produced shared attributes of religion, art, political structure and hierarchical society? Last month, the simmering pot of mother-sister controversy was stirred anew by Dr. Jeffrey P. Blomster, an Olmec archaeologist at George Washington University. In a report in the journal Science, he and other researchers described evidence of the widespread export of Olmec ceramics that they said supported "Olmec priority in the creation and spread of the first unified style and iconographic system in Mesoamerica." Dr. Blomster's team analyzed the chemistry of 725 pieces of pottery decorated with symbols and designs in the Olmec style and collected throughout the region. The researchers compared the composition of the ceramics with local clays. They determined that most of these were not imitations of the Olmec style made by local potters. In a significant number of pots, the clay matched the chemistry of material found around San Lorenzo. "The evidence is overwhelming that San Lorenzo, the first Olmec capital, was doing the exporting," Dr. Blomster said. "The Olmecs were disseminating their culture and it was something of great interest to others." The research, he added, showed that San Lorenzo did not appear to be importing artifacts emblematic of other cultures or that regional contemporaries were exchanging such material with one another. The city on the artificial plateau seemed to be the hub of regional culture and central, he said, to understanding the origin and development of complex society in Mesoamerica. Dr. Richard A. Diehl of the University of Alabama wrote in Science that the findings "provide powerful support for the mother-culture school," adding, "San Lorenzo thus dominated in the commercial relationships and attendant spread of Olmec iconography and belief systems." But Dr. Diehl, a proponent of the mother school and the author of "The Olmec," published last year, said in an interview that the "connections we are seeing may not have lasted more than a generation, perhaps the time of a particular ruler, and at most, not more than a century or century and a half." The Blomster research dealt with pottery from the latter half of the early formative period of Mesoamerican culture, which extended from 1500 to 900 B.C. The last centuries of this period were the time of San Lorenzo's ascendance, but afterward the city was largely abandoned and the Olmec hub gravitated to La Venta, nearby in what is now the state of Tabasco. Dr. Blomster collaborated with Dr. Hector Neff, an archaeologist at California State University, Long Beach, and Dr. Michael D. Glascock of the Research Reactor Center at the University of Missouri. The Missouri center analyzed the pottery and clay samples from San Lorenzo and six other Mexican sites from the era of Olmec prominence. Proponents of the sister school are not letting the interpretation of the new research go unchallenged. They may be a minority in Mesoamerican studies, but a vocal and formidable one, including such stalwarts as Dr. Kent V. Flannery and Dr. Joyce Marcus of the University of Michigan and Dr. David C. Grove, a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois. Dr. Grove disputed Dr. Blomster's conclusions, saying that the research demonstrated only that Olmec pottery was traded, not that the trade disseminated Olmec political and religious concepts around the region. Others questioned the assertion that no pottery of other cultures had found its way to San Lorenzo. The mother-culture advocates, said Dr. Susan D. Gillespie, a Mesoamerican archaeologist at the University of Florida, who is married to Dr. Grove, were "flogging a dead horse, the idea that the Olmec invented civilization, carried it to all of Mesoamerica and it's the basis of the Maya." Dr. Gillespie acknowledged that the Olmecs established a vibrant culture and that their accomplishments were extraordinary. She also agreed that they were innovative and that their leaders presided over a political system capable of mobilizing labor for public works. It was no easy task raising an artificial plateau or hauling heavy blocks of basalt 40 miles to San Lorenzo from volcanic fields and fashioning them into the stone heads that stand as high as 10 feet. Olmecs also contributed games with rubber balls, which became popular and fiercely played by later regional cultures. The Aztecs, much later, used the name in their own language for "rubber people" - Olmec - to describe the culture that was by then long vanished but not forgotten. No one knows what the ancient Olmecs called themselves. "But others in the area were doing things equally complex, though different," Dr. Gillespie said. "Other areas were also taking steps on their own toward the development of Mesoamerican civilization." That, and an active interchange of ideas and beliefs among various neighboring societies, is the essence of the argument advanced by sister-culture proponents. They further contend that the concept of the Olmecs as a mother culture grew out of 19th-century ethnocentrism, in which the construction of stone sculptures is a sign of civilization because that is a hallmark of early Western civilizations. Many of these archaeologists have concentrated their research and excavations on nonOlmec areas with evidence of ancient complex societies, like the Valley of Oaxaca, the central basin of Mexico and the Pacific coastal sites of Chiapas in southwestern Mexico. Dr. Gillespie, though, has studied Olmec workshops that were operating in the culture's heyday, mainly producing stone artifacts thought to be altar thrones. Dr. Blomster cited recent excavations by Dr. Ann Cyphers of the National University of Mexico that "emphasize the higher sociopolitical level that the Olmecs achieved relative to contemporaneous groups in Mesoamerica," a view contrary to the sister-culture position. Dr. Cyphers said the rulers of San Lorenzo appear to have lived in a palace with huge basalt columns and sculptures, while leaders in the adjacent Valley of Oaxaca had places not much better than the wattle-and-daub huts of commoners. Dr. Michael D. Coe, an archaeologist at Yale who is an authority on the Olmec and the Maya cultures, sides more with the mother-culture school, saying that "much of the complex culture in Mesoamerica has an Olmec origin." In the new edition of his book "The Maya," Dr. Coe writes that during four centuries of San Lorenzo's prime, ending about 900 B.C., "Olmec influence emanating from this area was found throughout Mesoamerica, with the curious exception of the Maya domain perhaps because there were few Maya populations at that time sufficiently large to have interested the expanding Olmecs." But early Olmec rulers were aware of the territory where the Maya eventually established imposing cities. Three years ago, scientists reported finding a rich lode of jadite, including huge boulders of it, in the jungles of Guatemala. Traces of ancient mining were uncovered, and some of the outcroppings were of blue jade, the prized gemstone Olmec artists used for carving delicate human forms and scary masks. Archaeologists said the discovery not only solved a mystery of the origin of Olmec jade, but also showed that the Olmecs exerted wide influence over the region, either directly or by trade through intermediaries. The Olmec influence on the Maya began to show up in artifacts, starting before 100 B.C. By then, Dr. Coe and other scholars said, Olmec art, religion, rubber-ball games and the ceremonial dress of rulers had clearly found its way to Maya cities. Dr. Diehl of Alabama said there was "good evidence that Olmec sculpture is portraying beliefs" also related in Popol Vuh, the epic of creation found in Maya writing. This cosmology predated the Maya and was widespread in Mesoamerica, but its origins are murky. The classic maize god of the Maya, scholars say, appears to be a clear descendant of a similar Olmec god. A Maya wall painting in San Bartolo, Guatemala, shows a resurrected maize god surrounded by figures offering him gifts of tamales and water. "The deity's head is purely Olmec," Dr. Coe said. The assumption is that aspects of Olmec culture reached the Maya indirectly, probably through what is known as the Izapa civilization in the territory extending from the Gulf Coast across to the Pacific Coast of Chiapas, in Mexico, and of Guatemala. The city known as Izapa is the site of imposing temple mounds in Chiapas, a place where the Olmec sculpture and Maya painting and glyphs seemed to converge. Dr. John E. Clark, an archaeologist at Brigham Young University, has excavated in the area for years and is involved with current research, he said, showing strong links between San Lorenzo and ancient sites in Chiapas. From there, Dr. Clark said, the influence of the Olmecs - not only their art and gods but their kingship and all its trappings - eventually penetrated deep into Maya country and its rising cities. It appeared to be a melding of late Olmec culture with preclassic Maya. Some early carvings of Maya kings, he said, were made on the backs of Olmec jade pieces. A comparison of their art reveals that Maya and late Olmec kings dressed in similar style, resplendent in jade and feather capes like their shared gods. In his journal commentary, Dr. Diehl supported the Blomster team's research as the largest and most comprehensive study ever conducted on the spread of Olmec pottery. The research appeared to show, for example, that the exchanges of pottery and presumably other goods were arranged between Olmec rulers and specific foreign lords "rather than the more diffuse trade networks posited by sister-culture proponents," Dr. Diehl said. But left unexplained, he added, was how "this was accomplished and what motivated people on both ends." Were these truly commercial ventures? Dr. Diehl said there was so far no archaeological evidence suggesting that the Olmecs conquered or proselytized its neighboring societies. Neither is there a clear picture of what happened to San Lorenzo. Nothing in the ruins or later legends points to conquest by an invading army. More likely, some scientists think, the city was abandoned by the ninth century B.C. because of natural catastrophe: the rivers they depended on probably changed course, the result of silt and tectonic shifts in the coastal landscape. La Venta, the new capital, came to an equally mysterious end around 400 B.C., and it was not long until the Olmecs lapsed into decline. Pockets of the culture persisted in Tres Zapotes, near the former capitals, and scattered communities in southern Mexico. By the time the first major civilization of Mesoamerica was disappearing, the Olmecs blending into other societies, it apparently had reached out far enough in trade and influence to pass on a legacy of politics, art and religion to the up-and-coming Maya. A few mother-culture archaeologists, citing the new research, liken the relationship of the Olmecs to the Maya to the Greeks and Romans of Western civilization.