Jürgen Wasim Frembgen: From Popular Devotion to

advertisement

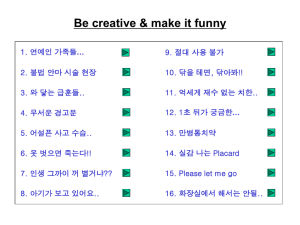

Jürgen Wasim Frembgen From Popular Devotion to Mass Event: Placards advertising the Pilgrimage to the Sufi Saint Lal Shahbaz Qalandar in Sehwan Sharif (Sindh/Pakistan) Introduction Shaikh Usman Marwandi (d. 1274 CE), better known as Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, is the pivotal figure of the Qalandariyya, a mystic brotherhood and antinomian movement originating in the early thirteenth century around Eastern Iran and Middle Asia in the course of the Mongol invasion. Over the centuries he became one of the most celebrated Sufi saints in Pakistan and the one with the largest following especially among the poor and downtrodden. The annual ‘urs festival at his shrine in Sehwan Sharif in the southern province of Sindh, commemorating the death of this charismatic miracle-worker and ‘intoxicated’ friend of God, turns into a carnival-like mass event combining the fervour of devotion and ecstatic performances of trance dance with more mundane fun and joy of life. Colourful placards (ishtehār) invite people mainly to join in the pilgrimage (ziyārat) and participate at the ‘urs, but also at other commemorative ritual events (shām-e Qalandar, jashn-e Qalandar) dedicated to this saint. They are media of religious advertisement providing a deeper understanding of the institutionalization of his cult, particularly about the organisation of pilgrimage, local networks of devotees and expressions of Qalandar piety. As already mentioned in an article dealing with placards of saints’ festivals in the Muslim Punjab, these print media of mass communication represent a hitherto neglected source for the study of popular shrine-oriented Islam in Pakistan.1 The present paper supplements this more general overview and follows the same structural outline in describing and analysing such prints. Whereas my earlier documentation is based on a larger data base of 116 placards, I could collect or photograph thus far a total of 30 polychrome placards focusing only on the veneration of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar between 1999 and 2010.2 As a result of the enormous popularity of his cult throughout the country, this saint is advertised by far the largest number of different placards. The same holds true for the variety of devotional posters depicting him and his shrine.3 The placards measure on average between 50 x 75 cm and are, with one exception, all in vertical format. They are printed in Lahore and distributed from there and thus prove the special attachment of Punjabi devotees as well as the wealth and economic power of their sponsors. In comparison with other placards from the Punjab, Qalandar 2 pilgrimage placards from Lahore are mostly larger in size, show a larger number of pictures and are printed in better quality with many colours. Many of them have thin metal borders at both short ends and a loop for hanging. Those are not as usually pasted to walls in the urban public space, but hung up in shops, restaurants and tea-houses and thus more durable. Placard Images Without repeating characteristics of composition and calligraphy, which Qalandar placards have in common with other ‘urs placards in Pakistan, I want to focus on the fact that some of them are literally loaded with images. The main motifs, placed in the upper part of the placard, are depictions of the saint’s shrine and his richly decorated tomb found on each of the 30 placards documented here. With one exception only photographs have been used. They show the tomb (15 times), the tomb in combination with the shrine (7 times), the western facade of the mausoleum (4 times), the shrine seen from the south (once) and the shrine of Imam Husain in Karbala as a substitute (3 times). The figure of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar is shown once on a placard dating from 1999 in his typical postures of praying and dancing whereby this depiction was borrowed from a Sufi poster; recently three placards show him together with his beloved disciple Bodla Bahar.4 Given that the saint’s iconic image is ubiquitously found in contemporary devotional mass media, this comparatively small number of saints’ images seems first surprising, but one needs to take into account that the genre of traditional painted Sufi posters is recently diminishing in importance being replaced by composite cut-and-paste prints and even more by photographic depictions. In the information age of the early 21st century posters are simply less available to be scanned by the young graphic-designers composing placards today on the computer. The photographic portraits of devotees and sponsors, found on 14 prints, are placed in the lower part of the placard or as a frame around the main sacred motif which is either a picture or a calligraphic reference to the ritual event. Placards containing such portraits are generally composed more symmetrically than those without which only contain text. The number of images can be reduced to one or two (such as in the case of Sain Zawar Husain Naqvi depicted as a dervish, No. 29), but more often they grow into a veritable picture gallery.5 To give a few examples, I first want to mention a placard (No. 7) showing besides the Qalandar’s tomb just a single photograph of a living saint, namely Hazrat Baba Jamil Ahmad Naqib Alvi Qalandar from Lahore.6 Measuring 11 x 16 cm his photo is larger than any other portrait of a devotee found on Punjabi saints’ placards. Apparently his saintly status does not 3 permit his picture to be lumped together with those of common devotees. Whereas the latter are almost always depicted in the frontal bust position of passport photographs, a saint can also show a specific devotional gesture as in the present case where the bearded Baba, shrouded in a veil, with prayer beads around his neck also holds a rosary in both hands stretched out in the position of offering du‘ā. Together with another Qalandar Baba carrying the nasab Alvi, his name is mentioned first in the list of organisers of the pilgrimage to Sehwan Sharif. The next placard (No. 18) is extremely rare showing two photographs of female dervishes in addition to a view of the shrine in Sehwan Sharif before its renovation. It announces a shām-e Qalandar (nightly commemorative ritual) in the Walled City of Lahore celebrated in honour of the great Qalandar saint in the name of the two ladies. Both, the elder one, Mai Hajjan Nasir Bibi Qalandri, who had passed away, and the younger, Sayyan Charagh Sahiba, are depicted with their hair uncovered. In comparison to other placards, this print is rather unpretentious in composition and layout without ornamented shapes for textual information and without prominent calligraphy. Thus, it can be assumed that it was printed in a small press probably in the old city of Lahore. In the third example (No. 1), the photograph of the Qalandar’s tomb and the elaborate calligram ‘urs mubarak – ‘blessed ‘urs’ – in the centre is surrounded by a picture gallery consisting of 50 passport portraits. Most of the latter are arranged in three long rows in the lower part of the placard. The only exception from these bust portraits is a photograph of a devotee named Poli Sain who wears necklaces, is shrouded in a red chadar and is circled with money in a traditional gesture. Generally speaking, the insertion of portraits (even of baby devotees as seen on No. 3) into a placard is done on special order; otherwise the printer just provides a template-design with a photograph of the shrine, the calligraphed name of the saint and blank shapes to be filled with the text supplied by the customer (No. 19). Interestingly, the organisers who commissioned the placard in question in 1999, in which the most prominent members of their association of devotees, the Jhule Lal-sanghat 7, are depicted in portraits, opted for an almost un-iconic placard two years later. This placard (No. 8), with only two portraits, has the names of the sangat’s members now written in button-like oval shapes. Placard Texts Sacred words and pious formulas 4 Similarly to other ‘urs ishtehar from the Punjab, most of the Qalandar pilgrimage placards have calligraphic or pictorial references to God and the Prophet Muhammad as usual placed in the uppermost part side by side with the basmala and further invocations of the holy family (panjtan pāk). Nevertheless, this most sacred part of the print is more prominently adorned by verses eulogizing Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, for instance by the well-known Persian couplet beginning with haidariam qalandaram mastam (Nos. 2-5, 7, 12, 15, 17) as well as the following verses in Urdu (Nos. 4, 8, 6, 14): Chaukhat hai Qalandar kī gharīboñ kā sahārā, mit-jātā hai har gham us-se jab bhī pukārā. – ‘The threshold to the Qalandar is a help for the poor, every sorrow will come to an end if we call upon him.’ Har dil men har ankh meñ hai armān Qalandar kā Jhule Lāl, qismat wālā bantā hai mehmān Qalandar kā Jhule Lāl. – ‘In every heart (and) every eye there is the longing for Qalandar Jhule Lal. If you are fortunate, you will be made the guest of Qalandar Jhule Lal.’ Nigāh-e Qalandar meñ woh tāsīr dekhī, badaltī logoñ kī taqdīr dekhī. – ‘In the eyes of the Qalandar I found such qualities, (and) I saw the fortune of the people.’ Other placards (Nos. 12, 8) show Punjabi verses; the first became famous by the singer Madame Nur Jahan: Shahbāz kare parwāz jāne rāz dilāñ de, jiundere te Lāl Qalandar ān-milāñge. – ‘The royal falcon flies, he knows the secrets of the hearts. If we are still alive, we will meet at (the shrine of) Lal Qalandar.’ Ka’abe ‘Alī dā te jhukde sikandar, tarīqat dā pehlā namāzī Qalandar. – ‘The king bows before the highest Kaaba, the Qalandar is the first pious on the mystic path.’ In addition, there are invocations to Data Ganj Bakhsh, the patron-saint of Lahore (Nos. 1, 8, 12), to Shah Bilawal Nurani, the saint from Lahut Lamakan and Nurani in Balochistan (Nos. 1, 12), and frequently formulas eulogizing Ali and the twelve Shi’ite Imams. As Twelver Shias, especially from the Punjab, claim that Lal Shahbaz had been a Shi’ite, Ali is often mentioned together with him, for instance in the formula jāne yā ‘Alī Jhule Lāl (No. 14), the famous Arabic invocation quoting Ali’s sabre dhū’l-fiqār (No. 1) and in Persian verses emphasizing the Prophet’s nomination of Ali as his rightful successor (Nos. 1, 3).8 The connection between the first Imam of the Shias and the Qalandar saint is also highlighted in the following Urdu verse (No. 4) through a reference to Ali’s burial place in Najaf: 5 Be sabab chumte nahīñ Sehwan kī zamīn ko, is mattī se khushbu-ye Najaf ātī hai. – ‘It is not without reasons to kiss the soil of Sehwan, (as) from this earth the fragrance of Najaf emanates.’ Placards with such verses and invocations are a public affirmation not only of Sufi devotionalism, but particularly of Shi’ite identity. Titulature of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar In addition to sacred words and pious formulas, the upper or more often central part of the placard contains the name of the Qalandar and his honorific titles. Thus, stringing grand titles together, he is officially named Hazrat Sayyid La‘l Shahbāz Qalandar, often accompanied by the sobriquets sākhī sarwar sarkār (‘bounteous leader and master’), lajpāl (‘the lord who gives us life’) or kibrīyā (‘the great’). Occasionally, his vernacular laqab Lal Shahbaz and the nisba Qalandar is followed by his personal name Usman and the nisba Marwandi referring to his place of birth in northwest Iran. He is praised as ‘alī la’l (‘highest Lal’)9, mast (‘the intoxicated one’)10 and in idiomatic Punjabi as jattī-sattī (‘powerful’).11 Further he is reverently addressed as pīr-o-murshid (‘Sufi master and spiritual guide’) and walī-ye Sindh (‘saint/ruler of Sindh). On one placard the saint is only addressed by his nickname Jhule Lal (No. 14). Basic information Alongside the mention of the ‘urs (in the form of a prominent calligraphic sign in the centre of the placard) the number of this annual event is given (for instance 748 in the year 2001), the dates in the Islamic lunar and in the Gregorian calendar as well as the location, that is to say Sehwan Sharif. If it is, however, a shām-e Qalandar preceding the ‘urs, also the date and place of this devotional ritual is mentioned. Necessarily all pilgrimage placards contain information about the date of departure of the procession of pilgrims – the ‘caravan’ (qāfila) – and the place in Lahore where the pilgrims are going to assemble. Often the procession starts from the house of the main organiser and moves to the railway station from where the journey starts down to the southern province of Sindh. Organisation – The Network of Devotees The textual information in the lower part of the placard not only provides insights into the organisational framework of the respective qāfila qalandrī (lit. ‘caravan of Qalandar pilgrims’) and/or sanghat (association of devotees), but also into the social fabric of these 6 regional networks centred upon devotional practices. List of names are generally arranged in a hierarchical order whereby the prominent organisers and devotees are often brought out by their portraits. They reflect an exclusively male corporate membership. Names and titles are revealing in the sense that they tell about the individual’s origin, religious denomination or official position (through nisba), ethnic affiliation (through nasab), professional and occupational background as well as individual idiosyncrasies (through laqab). Associations organising the pilgrimage to Sehwan Sharif and their stay in this town are apparently less institutionalized than those organising the actual ‘urs of a saint. Thus, the comparison of Lahori pilgrimage placards and Punjabi ‘urs placards shows that the former only inform about a handful of organisational functions whereas the latter reflect the bureaucratized management of shrines. Our placards, for example, at best give the headings zer-e sarparastī (‘under the direction’), zer-e nigrānī (‘under the auspices’), zer-e qiyādat (‘under the leadership’) or zer-e sadārat (‘under the presidentship’) denoting those leading the caravan of pilgrims. Sometimes the organisation committee is just subsumed under the headings intezāmīa (‘under the care of’), muntazamīn (listing the superintendents and managers) or minjānib (‘in the name of’). Guests can be addressed as mehmān garāmī (‘appreciated guests’) and mehmān khusūsī (‘special guests’). Occasionally the langar-incharge (persons organising the ‘free kitchen’ during the stay in Sehwan) and dhammālie (dancers) are named. Often no office holders at all are mentioned, the qāfila or sangat just represents itself as a collective. The main responsible organisers are usually leading Sufis and Khalifas of saints, but also high status bureaucrats who humbly call themselves Haidari-Malang although strictly speaking they do not lead the lives of religious mendicants. Among the dignitaries and special guests we find politicians, landlords, high officials (such as Commissioners and people from army and police) and businessmen. Other devotees belonging to the sanghat can be subsumed under the heading khādmīn-e Qalandar (‘servants of the Qalandar’). A peculiarity of Lahori pilgrimage placards is that they also mention nicknames so typical and colourful especially for the old part of this city. However, for the study of the social composition of devotees’ associations and their networks, the nasab, the nisba indicating the place of origin and the laqab indicating the occupation are more revealing. For instance, the placard of the Jhule Lal sanghat group No. 21 in Lahore, which honours Lal Shahbaz Qalandar in the name of the late Chaudhry Imtiaz Husain, lists altogether 98 personal names (No. 1). Nasab like Jat, Bhatt, Gujar, Satti and Arain show that the sangat is a collective entity cutting across the boundaries of qaum (ethnic group), zāt (caste) and birādarī 7 (‘brotherhood’, kin group within castes). Secondly, the frequently mentioned nisba Samundriwale points to the origin of these individuals from the qasbah Samundri in the vicinity of Faisalabad in Central Punjab. This exemplifies the well-known social pattern that many Lahorites, in fact, migrated to the city from the countryside. Nisbas mentioning place names on our placards indicate that devotees predominantly live in and around the Walled City as well as in other traditional quarters. Nevertheless, there are also other Qalandar networks (No. 7) where some of the main followers of a living Qalandar saint from Lahore come from other towns in the Punjab, such as Gujrat, Jhelum, Chakwal, Narowal or Sahiwal. Thirdly, occupational laqab document that members of the respective sanghat No. 21 work as fishsellers, butchers and barbers or in restaurants, for instance as cooks. Names on other placards prove a similar variety of professions from bank officers, police inspectors and car dealers to bread bakers, chicken vendors and makers and –sellers of tea, lassī12 and lentils. Bound together as members of the same sanghat during the devotional rituals of pilgrimage, ‘urs and shām-e Qalandar creates a sense of brotherliness and equality. The bottom of the placard sometimes contains the names of wealthy devotees, often together with their company’s name, who sponsor printing and distribution as well as the ritual proceedings. They can be the owners of a forwarding agency (No. 1, 8), of a company for metalwork and packages machinery (No. 4, 8), building contractors and agents for cranes (No. 11), of a company selling ice-blocs (No. 11), but also of a textile store (No. 6) or pānshop (No. 15). One placard (No. 9) explicitly mentions that the donation (‘atīah) for printing the placard had been received by a man from the Walled City who works as a bag-wālā, that is to say somebody selling travelling bags. The names can be introduced by pious invocations, such as adhai ul-khair (‘please pray for me!’). Programme Unlike ‘urs posters in the Punjab which give detailed information on the rituals and ceremonies taking place at the saints’ festivals, Lahori pilgrimage placards advertise and publicize the event as such. Thus, they usually provide basic data about the date of the festival, the departure of the qāfila qalandrī from Lahore railway station and the place (qiyām) in Sehwan Sharif, sometimes also about the langar. The latter is found in a small section entitled progrām at the bottom of the placard. Shām-e Qalandar placards, on the contrary, focus more on different ritual events, such as the actual Qalandar-night, mehndī and dastar-bandī ceremonies as well as the departure of the qāfila to Sehwan (No. 3). The programme on placard No. 18 starts with qur‘ān khwānī, chadar-o-dhammāl performed after 8 evening prayers, followed on the next day by mehfil-e samā‘ mentioning the names of the qawwalī singers and pehlī dhammāl qadīmī. The La‘l Shahbāz Qalandar mehfil-e sama’ is ended by rasm sehrā, the ceremony of the binding of garlands. Conclusion Placards advertising the pilgrimage to Lal Shahbaz Qalandar on the occasion of the saint’s ‘urs are above all printed in Lahore and distributed from there. Examining their visual and textual information through the network lens helped to analyse the institutionalization of this Sufi saint’s cult which is especially popular among Punjabi devotees since the 1960s/1970s and borders on fandom. I argue that Qalandar pilgrimage placards are media of mass communication offering insights into contemporary Sufi devotional practices as well as the hierarchical organisational framework and the social composition of pilgrims’ associations.13 Sanghats constitute inclusive moral communities which cut across the boundaries of qaum, zāt and birādarī. Within the confined context of devotion to a Sufi saint their members share a collective identity as followers of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar. Finally, it should be emphasized that the material presented here very briefly calls for a closer study of such Sufi networks in Pakistan. Notes Frembgen 2009 b. – There are treatises serving as guides to visit the tombs of Sufi saints alongside Muslim calendars listing saints’ festivals. For an example of a manual from the 18 th century, see Ernst 1993. 2 The following placards are part of the collection of the Museum of Ethnology in Munich: No. 1 (Inv.-No. 99321 518), No. 2 (Inv.-No. 99-321 519), No. 3 (Inv.-No. 99-321 520), No. 4 (Inv.-No. 02-324 095), No. 5 (Inv.No. 02-324 016), No. 6 (Inv.-No. 04-326 224), No. 7 (Inv.-No. 99-321 521), No. 19 (Inv.-No. …). The placards numbered 8-18 are photographs taken by the author in Lahore. 3 Frembgen 2009 a. 4 Frembgen 2006: 67, 69; Frembgen Ms. 5 Frembgen 2009 b. 6 The nasab Alvi shows that the person in question is a descendant of Ali, the fourth caliph and first Shi’ite Imam, but from other wives than the daughter of the Prophet. 7 An equivalent term is anjuman ghulāmān Sākhī Lāl Shahbāz Qalandar. In Lahore alone there are hundreds of sangats, each under the leadership of a sarbara. The term sangat (originally a Sanskrit word), meaning ‘union’, ‘association’ or ‘society’, is also used for branches of a Sufi order. In other contexts, this term is commonly used for circles of Shi’ite mourners (matami sangat) and circles of poets. 8 Concerning Shi’ite symbols in the cult of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar see Boivin 2007: 166-168. 9 This invocation is echoing the ‘Alī Allāh formula written on banners and displayed during the ‘urs above the main entrance of the darbār of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar (cf. Boivin 2007: 167). 10 This alludes to the Qalandar characteristic of being ‘perpetually intoxicated’ (damādam mast Qalandar), particularly attributed to Lal Shahbaz Qalandar. 11 This Punjabi echo word refers, in fact, to a rural Jat woman (jatī) who is considered strong, robust and hard working. 1 9 12 Beverage made in the Punjab of yoghurt mixed with water, milk, salt and spices. What C.W. Ernst remarked about the use of printed books in traditional Sufi genres (such as hagiographies, discourses, essays, manuals on prayer and meditation) also holds true for our placards: ‘… through the wider distribution made possible by print, such publications have both served local Sufi networks and at the same time functioned as proclamations that have at least potentially formed part of the public legitimisation of Sufism. Through these modern public media, Sufism is no longer just an esoteric community constructed largely through direct contact, ritual interaction, and oral instruction’ (Ernst 2005: 198-199). 11 References Boivin, Michel: Representations and Symbols in Muharram and Other Rituals: Fragments of Shiite Worlds from Bombay to Karachi. In: A. Monsutti, S. Naef, F. Sabahi (eds.), The Other Shiites. From the Mediterranean to Central Asia; p. 149-172. Bern 2007 (Peter Lang). Ernst, Carl W.: An Indo-Persian Guide to Sufi Shrine Pilgrimage. In: G.M. Smith & C.W. Ernst (eds.), Manifestations of Sainthood in Islam; p. 43-67. Istanbul 1993 (The Isis Press). Ernst, Carl W.: Ideological and Technological Transformations of Contemporary Sufism. In: M. Cooke & B.B. Lawrence (eds.), Muslim Networks from Hajj to Hip Hop; p. 191207. Chapel Hill and London 2005 (The University of North Carolina Press). Frembgen, Jürgen Wasim: The Friends of God – Sufi Saints in Islam. Popular Poster Art from Pakistan, Karachi 2006 (Oxford University Press). Frembgen, Jürgen Wasim: Icons of Love and Devotion: Sufi Posters from Pakistan depicting Lal Shahbaz Qalandar. In: Journal of the History of Sufism 6 (2009 a) [in press] Frembgen, Jürgen Wasim: Words and Images in the Muslim Public Space: Placards advertising Sufi Saints’ Festivals in the Pakistani Punjab. In: I. Flaskerud & J.W. Frembgen (eds.), Images and Visual Representations in Muslim Popular Culture (forthcoming).