Building an evidence-base for the Civil Justice System

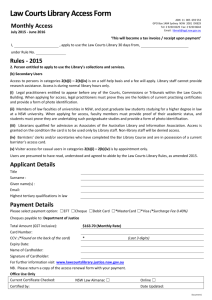

advertisement