CoTeaching

advertisement

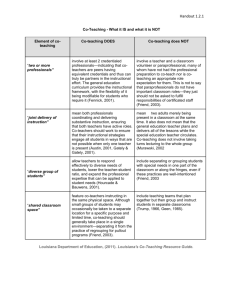

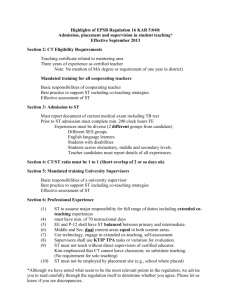

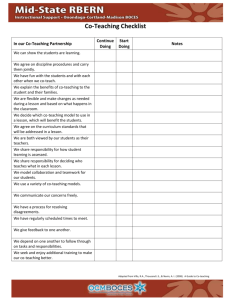

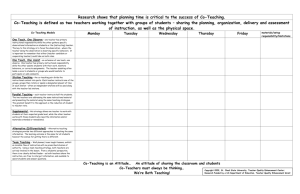

Co-Teaching Background: Tobin (2005) describes the co-teaching approach as “a restructuring of teaching procedures in which two or more educators possessing distinct sets of skills work in a coactive and coordinated fashion to jointly teach academically and behaviorally heterogeneous groups of students in integrated educational settings” (p. 785). Coteaching has become a popular model in many schools due to shortages in classroom space and the inclusion of special education students in the regular education classroom. In addition, co-teaching provides teachers with the opportunity to collaborate more effectively, develop assessments of learning for all students in the classroom, and follow closely the testing modifications prescribed in Individual Education Plan or Section 504 plan for students with disabilities (Wischnowski et al., 2003). Research Findings: Most research on co-teaching has been found in the exceptional student education literature. Murawski & Swanson (2001) analyzed research on teams of special education and general education teachers and found significant gains in reading, math (for students with learning disabilities), and minimum competency tests. Similarly, Chalfant & Pysh (1989) found comparable data in their analysis of teacher assistance teams. Preliminary data indicated that student performance and behavior were enhanced, behavior problems reduced, and more support was provided for students and professionals in school settings where general education and special education teachers work together. Furthermore, several surveys conducted on students, parents, or teachers revealed satisfaction and reported positive outcomes associated with co-teaching. More positive perceptions were also associated with administrative support, additional planning time, similar beliefs about teaching, and mutual respect of one another. However, Weiss and Brigham (2000) listed several overall problems with co-teaching research, including the following: 1) omitting important information on measures; 2) interviewing teachers only in cases in which co-teaching is successful; 3) finding in many cases that teacher personality was the most important variable in co-teaching success; 4) lacking a consistent definition of coteaching; and 5) stating outcomes subjectively. Furthermore, some predictable sources of conflict have been identified among co-teachers, including different positions regarding instructional beliefs, use of planning time, parity between teachers, agreement on classroom routines, and rules about confidentiality, noise, and discipline (Cook & Friend, 1995). Implications for Instruction: When implemented carefully, co-teaching can help schools create inclusive classrooms for students with special needs and also improve learning and address the classroom shortage problem. Piechura-Couture et al. (2006) provides a three-step process that is helpful in setting up effective teaching teams. The first involves matching compatible pairs of teachers using philosophical and learning styles inventories. Leahy's Educational Philosophy Inventory may be used by administrators to identify the philosophical orientations of the teaching pairs. This inventory was developed to identify six of the most prominent perspectives in education philosophy: essentialism, behaviorism, progressivism, existentialism, perennialism, and reconstructionism. The 36item inventory contains a series of statements about the aims of education and explores teaching, learning, curriculum, and governance. Knowing the learning and teaching style of each partner can help create a balanced classroom for both teachers and students. The second step entails teaching teaming strategies that have been identified as successful in co-taught classrooms. Vaughn, Schumm, and Arguelles (1997) describe five basic models of co-teaching. The first, "one teach-one assist," requires both teachers to be present with one teacher taking the lead in delivering instruction; the other teacher monitors or assists students individually. In the second model, "station teaching," each teacher takes responsibility for teaching part of the content to small groups of students who move among stations. Teachers divide students into three groups, two working with teachers and one group working independently. Students rotate among the three stations over a pre-determined block of time. With the third model, "parallel teaching," teachers plan instruction together but split the class and deliver the same instruction to smaller groups within the same classroom. With the fourth model, "alternative teaching," one teacher works with a smaller group of students to re-teach, pre-teach, or supplement the instruction received by the larger group. Finally, in "team teaching," the fifth model, both teachers share the instruction of all students at the same time. The third step includes reducing obstacles and barriers before implementing the co-teaching model. The following barriers were identified by school administrators during a co-teaching workshop and may be used by schools as discussion starters: staff development, division of labor among teams, getting teams to “share the load”, integration of various teaching and learning styles, lack of training on the part of teachers and administrators, compatibility of personalities, fear of change, control issues between teachers, need for additional planning time, sharing of resources, parent perception, and student confusion. References: Chalfant, J. C, & Pysh, M. V. (1989). Teacher assistance teams: Five descriptive studies on 96 teams. Remedial and Special Education, 10(6), 49-58. Cook, L., & Friend, M. (1995) Co-teaching guidelines for creating effective practices. Focus on Exceptional Children, 20, 1-2. Murawski, W. W. & Swanson, H. L. (2001). A meta-analysis of co-teaching research: Where are the data? Remedial and Special Education, 22(5), 258-267. Piechura-Couture, K.., Tichenor, D. T., Macisaac, D., & Heins, E. D. (2006). Coteaching: A model for education reform. Principal Leadership, 6, 39-44. Tobin, R. (2005). Co-teaching in language arts: Supporting students with learning disabilities. Canadian Journal of Education, 28, 784-803. Vaughn, S., Schumm, J. S., & Arguelles, M. E. (1997). The ABCDE's of co-teaching. Teaching Exceptional Children, 30(2), 4-10. Walther-Thomas, C. S., & Carter, K. L. (1993). Cooperative teaching: Helping students with disabilities succeed in mainstream classrooms. Middle School Journal, 25, 3338. Weiss, M. P., & Brigham, F. J. (2000). Co-teaching and the model of shared responsibility: What does the research support? In T. E. Scruggs & M. A. Mastropieri (Eds.), Advances in learning and behavioral disabilities (vol. 14, pp. 217-245). Oxford, UK: Elsevier Science. Wischnowski, M. W., Salmon, S. J., & Eaton, K. (2004). Evaluating co-teaching as a means for successful inclusion of students with disabilities in a rural district. Rural Special Education, 23, 3-15.