Corpus-driven genitive disambiguation

advertisement

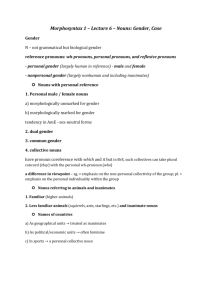

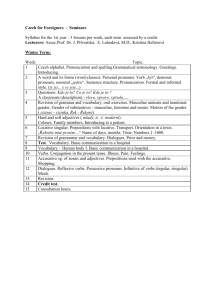

Corpus-driven genitive disambiguation Nadine Aldinger University of Stuttgart, IMS Azenbergstr. 12, D-70174 Stuttgart nadine.aldinger@ims.uni-stuttgart.de This paper describes work in progress on the corpus-based acquisition of morphosyntactic and lexical-semantic context parameters to disambiguate genitive attributes of German deverbal nouns. 1 Nominalizations and genitive attributes In my Ph.D. dissertation project I develop methods for semi-automatic text analysis to disambiguate genitive attributes of German deverbal nouns, especially those ending in –ung, like Verfolgung “persecution”. The suffix –ung is used to derive feminine nouns (mostly) from transitive verbs. It shares an etymological root with English –ing but forms full nouns. The meaning of – ung is comparable to that of the latinate suffix –(a)tion. As with many relational nouns – e.g. picture in Picasso’s picture –, genitive attributes of –ung nominals can be subject (agent-related, 1) or object (theme-related, 2) genitives: (1) a. Dort ist die Radioaktivität laut Messungen there is the radioactivity according-to measurements der Organisation hundertmal höher als normal. the-GEN organization a-hundred-times higher than normal “According to measurings of/by the organization, the radioactivity level is a hundred times higher there.” b. Der Satellit dient der Messung von Verschiebungen in der The satellite serves the-DAT measurement of shifts in the Erdkruste. earth’s-crust “The satellite serves to measure shifts in the earth’s crust.” In (1a), the genitive der Organisation “of the organisation” denotes the role-player who measures something (the radioactivity level), i.e. the thematic agent and grammatical subject of the nominal’s base verb messen “to measure”; in (1b), the genitive von Verschiebungen “of shifts” denotes the thing measured, i.e. the theme and grammatical object of the base verb. At the structural surface, both interpretations are possible in both cases. I do not distinguish between “genuine” subject genitive and author’s genitive, as Ehrich/Rapp (2000) do; for NLP-related work, the important matter is the semantic relatedness of the genitive attribute to the agent/subject/causer of the event/state/process characterized by the nominal’s base verb. There are also non-thematic genitives, e.g. temporal (die Lieferungen dieses Monats “the deliveries of this month”) and modal genitives (Lieferungen dieser Art “deliveries of this kind”). They are not restricted to nominalizations and therefore will not be treated further in this paper, although they must of course be detected and filtered out in the disambiguation process. See section 4.2 for a list. Human listeners use structural and semantic clues as well as world knowledge to disambiguate genitive attributes – e.g. in (1a) the knowledge that organizations more probably measure things than they themselves are measured. Automatic text analyzers for deep NLP also need to disambiguate genitive attributes, in order to provide input for information extraction and information retrieval. But they do not have a very elaborate “understanding” of the world (yet); in particular, they do not possess the world knowledge that humans have at their hands to determine the interpretation intended. Therefore it is a challenge to find clues for genitive disambiguation which can be assessed by computational tools. Usable features may be morphosyntactic (a,b) or lexical-semantic (c,d): a. morphosyntactic form of the DP headed by the nominal: i.e. number and definiteness, maybe case b. syntactic structure of the local context: inner structure of the nominal’s DP, but also embedding in PPs/VPs c. properties of the nominal’s base verb: e.g. telicity, syntactic subcategorization d. lexical material in the local context: e.g. selectional restrictions of the governing verb One can look for the most useful disambiguation clues from these categories in theories about nominalizations and their genitive attributes, generalizing that an interpretation will never occur in contexts in which it is not allowed according to theory. This approach has its drawbacks: the subtle semantic notions which linguistic theory uses are often hard to observe in real text. Therefore I decided to extract context parameters for genitive disambiguation directly from pre-annotated corpus text. If a text analyzer checks for such parameters when it encounters an –ung noun with a genitive attribute in corpus text, it should be able (ideally) to give the correct interpretation, or (in the real world) to give a weighted guess – here exemplified for the sentences (1a,b): In (1a), there is a plural head nominal Messungen “measurements”; the whole NP is embedded in a PP with the preposition laut “according to”. Additionally, the head lemma of the genitive, Organisation “organization”, can be classified as a collective noun even in a very shallow semantic analysis, e.g. using the German WordNet equivalent, GermaNet (Kunze et al. 2003). According to preliminary analyses, these three parameters – plural nominal, PP-embedding with laut, and collective nouns as head lemma of the genitive 2 attribute – occur significantly more often with subject genitives than with object genitives. Therefore they are good candidates to detect subject genitives. In (1b), on the other hand, the NP headed by the nominal Messung is the indirect object of the verb dienen “to serve”, which suggests that the subject is the actor of the nominalization. Together with the morphosyntactical features of the NP – definite singular – and the indefiniteness of the genitive attribute, this indicates an object genitive. The procedure I adopted to find and evaluate context parameters is outlined in section 2. Since my work not only aims at applications, but has some perspective on linguistic theory as well, it relies on semi-automatic, symbolic acquisition methods (aided, but not determined by statistics) rather than on statistically induced machine learning. 2 Procedure I am now building a database out of corpus examples for nominalizations and genitive attributes and annotate context parameter values (automatically) and genitive interpretation (manually) for each example. The corpus is morphologically annotated and chunked (see section 4.1). Steps: 1. Collect linguistic context parameters that might be relevant for genitive interpretation from literature and from (qualitative) corpus observations. 2. Collect corpus sentences containing representative nominalizations plus genitive attributes in a database and annotate their parameter values automatically. 3. Annotate genitive interpretation manually for each sentence. 4. Analyze frequency distributions to find the parameters and parameter combinations that are most useful to predict genitive interpretation. 5. Implement tests based on these combinations. 6. Re-run the tests on new corpus sentences and evaluate the quality of their predictions for genitive interpretation; if necessary and possible, improve the tests and look for more diagnostic parameters (bootstrapping). In this paper, I will concentrate on steps 1 to 4. Section 4 deals with data collection and annotation for the example database, and section 5 presents some first evaluations. 3 State of the art 3.1 Theory Some descriptive and theoretical work has been done on the interpretation of genitive attributes of nominals and their relation to base verb arguments. Two recent accounts are Ehrich/Rapp (2000) and Ehrich (2002). Taking a lexical-semantic approach, they generalize on the (un)grammaticality of certain genitive interpretations in combination with certain parameters: 3 sortal reading of the nominal (“sort” here defined as top-level entity class related to Aktionsart – the basic sorts are Process, Event, (resultant) State or (physical) Object): Process nominals can take subject genitives, Object nominals (generally) cannot. telicity and related lexical-semantic properties of the base verb: atelic (Process) nominals can take subject genitives, telic (Event) nominals cannot. number of the nominal: some plural telic nominals can take subject genitives under special semantic circumstances, singular telic nominals cannot. The first two parameters in this list are only very indirectly observable in corpora, therefore they are of limited use in automatic extraction tasks. Ehrich and Rapp confine themselves almost completely to artificially constructed examples and do not use their generalizations to predict genitive interpretation in real data. Hardly surprising, empirical analysis reveals that their general predictions are borne out in some cases but fail in others. A more comprehensive study of diagnostic features for genitive interpretation has, to my knowledge, never been carried out. Especially the clues that embedding structures (PPs, VPs) provide for the interpretation of genitives (or indeed, any syntactic construction) have not been investigated yet, neither from a theoretical nor from a practical viewpoint. 3.2 Methodology In work on extraction of linguistic information from corpora (in general) and disambiguation (in particular), there seem to be very few approaches to exploit context parameters at present. Spranger (2004) exploits the extraction of context parameters for chunking; the analysis of linguistic context parameters to detect collocations and idiomatic expressions has been proposed by Evert et al. (2004). Concerning ambiguities, precision-oriented (Eckle-Kohler 1999) and recall-oriented (Schulte im Walde 2002) approaches are to be distinguished. Eckle-Kohler’s grammar is specialized on the extraction of verb subcategorization frames and analyzes only unambiguous sentences. This yields a precision of 70-80%, but only 2% recall and leads to a need for very large amounts of text. Recall-oriented approaches mostly build on statistical methods; they have to accept ambiguous output and are often restricted to a coarse classification of the phenomena they extract. 4 Data collection and annotation 4.1 Corpus architecture The nominals and attributes for the example database are extracted from a German newspaper corpus (Frankfurter Rundschau 1992-93) with a size of about 40 million words. The corpus is 4 tokenized, lemmatized and part-of-speech tagged (using the STTS tagset, Schiller et al. 1999) with TreeTagger (Schmid 1994), morphosyntactically annotated and chunked with YAC (Kermes 2003). The IMS Corpus Workbench (http://www.ims.unistuttgart.de/projekte/CorpusWorkbench/), which is used to work with the corpus, provides a regular-expression query language, CQP (on-line demos at http://www.ims.uni-stuttgart.de/projekte/CQPDemos/cqpdemo.html), and a Perl interface to operate on the query results. I employ the latter to annotate values of specified context parameters to the query results and store them in a MySQL database (see section 4.2; http://www.mysql.com/). As an inflectional language, German displays a large amount of case/number syncretism. The morphosyntactic annotation in the corpus preserves the case/number ambiguities of nouns, adjectives, pronouns, and determiners by annotating sets of case/number/definiteness triples rather than single values or value sets. The chunker, YAC, reduces the ambiguities as far as possible on the chunk and phrase level by assigning to noun chunks and noun phrases the intersection of the sets of case/number/definiteness triples of their sub-constituents. Building on the disambiguated annotation, the chunker can attach post-nominal genitive NPs as attributes with reasonable precision. 4.2 Database layout The database consists of three tables: nominals: complete list of all -ung nominals (with or without genitive) in the corpus, including compounds verbs: subcategorization information about the nominals’ base verbs matches: all corpus matches of nominal + genitive attribute, annotated with context parameters First, a list of all –ung nominals in the corpus was compiled with a simple corpus query: [pos="NN" & lemma=".+ung"] After semi-manual deletion of false matches like Zeitung “newspaper” (not analyzable as a deverbal noun in present-day German) or Sprung “jump” (a non-deverbal noun accidentally ending in –ung), 36077 nominal lemmas were stored in the database, together with their occurrence frequency in the corpus. Compounding is a very productive word-formation process in German, and the database contains many compound nominals – e.g. 31 compounds with Abdeckung “covering, cover” as head, including Fahrbahnabdeckung “cover(ing) of a road”, Glasabdeckung “glass cover”, Winterabdeckung “cover(ing) for the winter” and Vollabdeckung “full cover(ing)”. This selection illustrates the variety of ways in which head and non-head(s) of a compound can be related. 5 Non-heads – i.e. the left parts – of compound nominals provide at least one useful clue for genitive disambiguation (as well as valuable information about compounding in general): If the non-head refers to the direct object of the nominal’s base verb as in Fahrbahnabdeckung, a post-nominal genitive attribute cannot be object genitive. To exploit this, I used the SMOR morphological analyzer (Schmid et al. 2004) to detect compound nominals and store their head lemma and non-head part separately. Subcategorization information for the base verbs is taken from an automatically compiled and manually corrected verb lexicon (Eckle-Kohler 1999). Verbs may have multiple subcategorization frames, some of which distinguish different verb meanings. Not all of these go into –ung nominal formation – e.g., Wartung can only be related to transitive etw. warten “to maintain (a machine)”, not to the much more frequent intransitive auf jdn. warten “to wait for s.o.”. Optimally, all nominals should be related to verb meanings in the database, not just to single verbs. For a more detailed description of the table of matches, see sections 4.3 and 4.4. 4.3 Extraction procedure The extraction query for nominal + genitive attribute exploits the genitive attribute attachment performed by YAC (see section 4.1). In addition, the query extracts some PPs headed by the preposition von “of, by” as “pseudo-genitive” attributes. The reason is that, in German, there is no way to express an unmodified indefinite plural genitive – except by paraphrasing it with a von-PP governing dative case (2b). There is no indefinite plural determiner in German, so an unmodified indefinite plural genitive DP (2a) would leave the noun’s case and number unspecified – regarding morphology alone, the noun (here Institute) could also be e.g. nominative singular. Definite plural genitive DPs are grammatical (2c) because here genitive case is marked on the determiner; and indefinite plural genitive DPs with an adjectival modifier (2d), which mark genitive case on the adjective, are grammatical as well. Thus, modified indefinite plural genitives can be distinguished from von-PPs with a modified inner NP (2e) – so the latter should (probably) not be treated as genitive paraphrases. (2) a. * die Messungen Institute the measurements institutes-GEN(?) (indef. pl. without modifier) b. die Messungen von Instituten the measurements of institutes-DAT (indef. pl. without modifier) c. die Messungen der Institute the measurements the-GEN institutes-GEN d. die Messungen bekannter Institute the measurements famous-GEN institutes-GEN e. die Messungen von bekannten Instituten the measurements of famous-DAT institutes-DAT (def. pl.) (indef. pl. with modifier) (“real” von-PP) As the chunker does not attach PPs at all, post-nominal von-PPs have to be extracted separately. The query excludes von-PPs with an article or adjectival modifier after the preposition, like (2e) or its definite counterpart, von den bekannten Instituten “of the famous institutes”. 6 To fill the table of matches, nominals from base verbs with certain selectional properties (e.g. verbs selecting for a prepositional or propositional object) are marked with a flag in the nominals table, including compounds. If the group is very large, only the nominals with the 20 most frequent heads are marked. Then a Perl script is invoked which collects all occurrences of the marked nominal + genitive attribute via CQP, automatically annotates their values of the specified context parameters and stores them (as whole sentences) in the database. (3a,b) are two simplified examples as extracted from the corpus: (3) a. der Gewinn, den sie durch Vermietung ganzer Etagen an the profit which they through renting whole-GEN floors-GEN to polnische Leiharbeiter erzielt hatten Polish casual workers made had “the profit they had made by renting whole floors to Polish casual workers” b. Die Bodenmessungen des städtischen Umweltamtes The soil measurings the-GEN municipal-GEN environmental authority ergaben katastrophale Ergebnisse. yielded disastrous results “The soil measurings of the municipal environmental authority yielded disastrous results.” Table 1 shows the context parameters currently annotated and extensions planned for the near future (see also section 7). To exemplify the annotation, the complete automatically generated annotations for (3a,b) are shown in the last two columns. feature number definiteness case specifier: word specifier: part of speech (STTS tagset) adjectival modifier(s) post-genitival PP: Features of the nominal and its NP values (3a) sg, pl sg def, indef, null (bare null singular) (set of) nom, gen, dat, acc nom, gen, dat, acc STRING ART (article: die, eine) PDAT (demonstrative pronoun: diese, …) PIAT (indefinite pronoun: keine, etwas, …) PPOSAT (possessive pronoun: seine, ihre, …) NE (proper name bearing genitive case) STRING an STRING 7 (3b) pl def nom, acc die ART - preposition post-genitival PP: case of governed NP for compounds: nonhead (set of) gen, dat, acc acc - STRING - Boden Features of the genitive NP / PP feature values (3a) number sg, pl, pp-von pl definiteness def, indef, null (bare indef singular) head lemma STRING Etage animacy and/or other STRING place? general lexical properties from GermaNet (Kunze et al. 2003)* Features of embedding context feature values (3a) preposition of STRING durch embedding PP main verb lemma of STRING erzielen the clause in which the nominal’s NP is an argument or adjunct* grammatical subject, direct object, adjunct function of the adjunct … nominal’s NP w.r.t. the clause verb* (3b) sg def Umweltamt institution? (3b) ergeben subject * planned Table 1. Automatically annotated context parameters Corpus annotation of number and definiteness is not always reliable – therefore I use morphology and especially the forms and lemmata of determiners to retrieve this information directly from the corpus. Since this procedure needs five different CQP templates (stored queries) to search for definite singular, definite plural, indefinite singular, indefinite plural and null singular nominal NPs, the values for number and definiteness of the nominal’s NP can be inferred from the name of the invoked CQP template. All other parameter values are not part of the query, but are determined by post-processing. 4.4 Classification of genitives In the example database, genitive interpretation is labelled manually for each corpus match. Frequency analyses of the annotation results will serve as basis to determine the most useful context parameters to be implemented in the semi-automatic genitive disambiguation tool. The following genitive labels may be assigned: 8 5 subject genitive: die Befürchtung der Gewerkschaft “the fear of the trade union” object genitive: die Befürchtung einer Finanzkrise “the fear of a financial crisis” subject genitive with non-transitive base verb: intransitive or unaccusative base verb – eine Erkrankung des Herzens “a disease of the heart”, base erkranken (intr.) “to fall sick”; inherently (or very preferably) reflexive verb – die Annäherung des Autos “the approach of the car”, base verb sich annähern (refl.) “to approach” other thematic genitives: in Ermangelung guter Alternativen “for lack of good alternatives”, base verb ermangeln (dummy subject, genitive object or an-PP) “to lack” non-thematic genitives: temporal – die Lieferungen dieses Monats “the deliveries of this month”; modal – die Lieferungen dieser Art “the deliveries of this kind”; with superlative – die (größte) Entdeckung der Ausstellung “the (biggest) discovery of the exhibition”; quantitative – eine Erhöhung von 3,5 % “a raise by 3.5 %” ambiguous instances: ambiguity between subject and object genitive is rare; more frequently: ambiguity, or rather vagueness, between subject and reflexive-subject genitive, due to different verb readings – die Angleichung der Lebensverhältnisse “the adjustment of the life standards”, base verb angleichen (tr./refl.) “to adjust s.th. / o.s.” genitive modifying the non-head of a compound nominal: die Altersverteilung der Studenten “the age distribution of the students” First results In a preliminary study, 16 –ung nominals from the semantic verb classes given by Ehrich/Rapp (2000) were taken as a test set. About 2000 corpus instances of these nominals with genitive attributes were annotated semi-automatically with morphosyntactic features, with the main purpose of testing Ehrich and Rapp's predictions on real text. It turned out that the subject-object genitive ratio for the 16 nominals was mostly determined by the following three parameters: number of the nominal (Verfolgung “persecution” vs. Verfolgungen “persecutions”) availability of Object reading for the nominal instance (i.e. whether the nominal can denote a physical object) (Herstellung “production” vs. Bearbeitung “revision”) – especially for mental Objects, i.e. “Object” instances of nominals from proposition-embedding verbs (Äußerung “utterance”) subcategorization properties of the nominal’s base verb Partly contradicting Ehrich and Rapp’s position, (a)telicity of the nominals’ base verbs does not seem to make much difference – except in indirect ways connected 9 with Object readings, which are generally unavailable for nominals from atelic verbs because the verbal semantics of atelics does not imply a specified result state. Evaluating the example database, I focus on these parameters in turn in the following three sections, returning once more to the role of lexical semantics in section 5.4. 5.1 Singular vs. plural nominals In the small test set, I followed Ehrich and Rapp’s approach by treating nominals from telic and atelic base verbs separately. For singular definite nominals from atelic verbs, like Verfolgung “persecution”, there are almost no subject genitives (two of 78 total genitives). Likewise, there are no subject genitives at all for the Process and Event instances of telic nominals like Absperrung “blocking off”. Pluralization of the nominal, however, reverses the relation – here subject genitives predominate: e.g. for Absperrungen (pl.), five of six genitive attributes are subject genitives. However, the plural nominals all have State or Object readings – so Ehrich/Rapp (2000) would classify the genitive attributes as “author’s genitive” at least for the Object nominals. Furthermore, there were no corpus matches at all (with a genitive attribute) for several plural nominals from telic verbs (Herstellungen “productions”, Errichtungen “establishings”, Unterstützungen “supports”, Vernichtungen “annihilations”) – note that, for all of these, the Object reading is unavailable. In the large, automatically annotated example database, 24007 corpus matches with 1050 different nominals are currently annotated with genitive interpretations (200506-13). The data confirm the effects demonstrated in the preliminary study. Table 2 shows the subject-object genitive ratio for all number-definiteness combinations, highlighting the influence of number. E.g., with definite singular nominals, there are about 13 object genitives for each subject genitive, while with plural nominals we have about three subject genitives for one object genitive. N-def def def indef indef null N-num sg pl sg pl sg gen.subj. gen.obj. others 626 7995 4184 507 188 596 593 1857 1568 436 153 254 565 1239 3246 gen.subj. 1 2.7 1 2.8 1 : : : : : : gen.obj. 12.8 1 3.1 1 2.2 Table 2. Genitive interpretation vs. number and definiteness of the head nominal in the example database 5.2 Object readings Some nominals, like Bearbeitung “revision”, Übersetzung “translation” and Unterstützung “support”, show a significant number of instances with subject genitives in singular; but these are almost exclusively Object nominals and fixed constructions like in Bearbeitung von Hans Schmidt “in a revised version by Hans Schmidt”. There are some interesting support verb constructions like Unterstützung finden “find support” where only subject genitives may occur – whether this support verb or others have the same effect on other nominals remains to investigate. 10 The difficult thing about Object readings is that they are hard to detect with corpuslinguistic methods. Heuristics for Object readings must rely heavily on semantics, e.g. embedding of the nominal’s NP under spatial verbs (stand, build) and prepositions (behind), or spatial modifiers (solid). 5.3 Subcategorization properties of base verbs A more detailed analysis clearly requires a closer look at other properties of the nominals involved, especially on the subcategorization (and perhaps thematic) properties of the nominals’ base verbs. The most striking example I found so far is the predictive power of proposition-embedding. Befürchtung “fear”, from the proposition-embedding base verb befürchten “to fear”, occurs almost only with subject genitives. The remaining object genitives themselves denote Events or Processes – e.g. die Befürchtung regulierender Studienverschärfungen “the fear of regulating tightenings of studying conditions”, or less clearly die Befürchtung einer Finanzkrise “the fear of a financial crisis”. The semantics of the nominal might explain this frequency distribution: Befürchtung denotes a proposition that someone utters or has in mind: a kind of mental Object. The subject genitive refers to the holder of the proposition, here the “fearer”. This analysis can be extended to other verbs subcategorizing propositions. Examples with similar genitive distribution are Äußerung “utterance” (base verb äußern “to utter”), Mitteilung “announcement, notification” (base verb mitteilen “to communicate”), and at least one sense of Feststellung “remark, observation, statement, conclusion” (base verb feststellen “to remark”) and even Messung “measurement” (base verb messen “to measure”), which at first glance does not have much to do with proposition-embedding mental Objects. 5.4 Embedding context Up to now, only embedding in PPs has been annotated and analyzed (for clausal embedding and grammatical functions see section 7). Strong biases of genitive interpretation in connection with certain prepositions are probably in most cases idiosyncratic to single nominals or small semantic groups. In combination with bare singular nominals, they often form fixed constructions like in Bearbeitung von Hans Schmidt “in a revised version by Hans Schmidt” (see also section 5.2) or auf Anweisung des Lehrers “on instruction from the teacher”. 6 Summary The exemplary data analyses highlight some parameters in linguistic context which a semi-automatic semantic text analyzer can use to disambiguate syntactic constructions and their semantic interpretations. The most striking example from the database up to now is the effect of number of the head nominal on the frequency of subject genitive attributes; more complex trails to follow involve e.g. the influence of base verb subcategorization properties. The first analyses demonstrate the possibilities of a corpus-driven perspective on disambiguation of real text. 11 7 Next steps In addition to enlarging the example database with more examples in the present state of parameter annotation, the annotation will be extended to more complex parameters, especially information about clausal context and grammatical function of the nominal’s NP and lexical-semantic information from ontologies (e.g. GermaNet). Since annotation of the former in a corpus would require full parsing, the main verb of the clause containing the nominal’s NPs, and especially the grammatical function of the NP with respect to the verb, will have to be annotated, or at least checked, manually in most cases. I also plan to extend the annotation of subcategorization parameters to thematic proto-roles in the sense of Dowty (1991) or Blume (2000). Proto-roles split the “traditional” thematic roles (a.k.a. semantic cases) into subproperties like causation or movement. Yet again, these proto-roles would have to be annotated manually for each verb, and I doubt that such properties can be applied consistently on abstract verbs. The use of ontologies will allow us to exploit some more heuristics from manual genitive classification, e.g. the observation that subject genitives are much more frequent with genitive attributes denoting a human, a group of humans or an institution. Information from an ontological hierarchy may also help to identify Object readings of nominals when they are grammatical subjects or objects of spatial verbs, as in eine Absperrung errichten “erect a barrier”. Finally, ontological information combined with information on grammatical functions helps to determine if the base verb’s object (or subject) is already occupied by another constituent in the sentence containing the nominal, ruling out the possibility that the nominal’s genitive attribute also refers to this category. References Blume, Kerstin (2000) Markierte Valenzen im Sprachvergleich: Lizenzierungs- und Linkingbedingungen (Tübingen: Niemeyer). Dowty, David (1991) Thematic proto-roles and argument selection. Language 67.3, 547-619. Eckle-Kohler, Judith (1999) Linguistisches Wissen zur automatischen LexikonAkquisition aus deutschen Textcorpora (Berlin: Logos). Ehrich, Veronika, and Irene Rapp (2000) Sortale Bedeutung und Argumentstruktur: ung-Nominalisierungen im Deutschen. Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft 19, 245-303. Ehrich, Veronika (2002) The thematic interpretation of plural nominalizations. ZAS papers in linguistics 27, 23-38. Evert, Stefan, Ulrich Heid and Kristina Spranger (2004) Identifying morphosyntactic preferences in collocations. Proceedings of LREC 2004, 907-910. Grimshaw, Jane (1990) Argument structure (Cambridge, MA: CUP). 12 Kermes, Hannah (2003): Off-line (and on-line) text analysis for computational lexicography (IMS, Univ. Stuttgart). Kunze, Claudia, Lothar Lemnitzer, and Andreas Wagner (eds.) (2003) Anwendungen des deutschen Wortnetzes in Theorie und Praxis: Beiträge des GermaNet-Workshops (Univ. Tübingen). Lindauer, Thomas (1995) Genitivattribute: eine morphosyntaktische Untersuchung zum deutschen DP/NP-System (Tübingen: Niemeyer). Reis, Marga (1988) Word structure and argument inheritance: How much is semantics? Linguistische Studien A 179, 53-67. Schiller, Anne, Christine Thielen, Simone Teufel, and Christine Stöckert (eds.) (1999) Guidelines für das Tagging deutscher Textcorpora mit STTS (Kleines und großes Tagset) (Institut für Maschinelle Sprachverarbeitung, Univ. Stuttgart and Seminar für Sprachwissenschaft, Univ. Tübingen). Schmid, Helmut (1994) Probabilistic part-of-speech tagging using decision trees. Proceedings of International Conference on New Methods in Language Processing. Schmid, Helmut, Arne Fitschen and Ulrich Heid (2004) SMOR: A German computational morphology covering derivation, composition, and inflection. Proceedings of LREC 2004, 1263-1266. Schulte im Walde, Sabine (2002) A subcategorization lexicon for German verbs induced from a lexicalised PCFG. Proceedings of LREC 2002, 1351-1357. 13